2018: The year of influence

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

I’ve decided to pick one theme from all the events and discussions of 2018. My aim with this post is to put influence into perspective. I’ve made this choice because of the sense that we reached a peak this year with so-called ‘influencer marketing’.

Let’s review what we know and where we are.

It’s not new. As a social species it’s always been important for humans to understand who has power and influence over us. We see this today with an obsession with celebrity. The upside of this phenomenon is that sharing gossip about celebrities is a bond that ties us together.

It is part of public relations. Whether you see the role as persuasion (advocacy), or community building (relationships), or communication, we work with others and through others. We need to identify influencers and work with them. As advisers, we seek to influence those in power.

We are, as Philip Sheldrake called his 2011 book, in The Business of Influence.

And yet others do not see it this way.

No one challenges that media relations is a public relations function. No one else lays claim to it (it’s never been called ‘media marketing’), to the extent that many of us are able to disown or downplay the practice.

Yet the new practices that have emerged over the past two decades are not labelled as public relations: they’re called ‘digital marketing’ or ‘content marketing’ or ‘influencer marketing’.

The danger of this marketing-led approach is that organisations take a transactional rather than a relational approach. (We in public relations should be alert to this danger because media relations has often been treated in the same way: we contact journalists when we’re seeking positive publicity, and we measure our success by the coverage achieved. Yet senior journalists are often in post for many years and we should recognise the value of building relationships with them over and above the coverage obtained for specific news stories.)

We also see this contrast between the transactional and the relational among digital and SEO specialists.

In the last decade, a new industry emerged asserting that ‘PR is dead’. Who needed the uncertainties and imprecision of media coverage when a much more technological (and expensive) solution could be found to influence (or game) search results?

A decade on, public relations has clearly not died, and digital specialists no longer publicly proclaim its death. Instead, they’ve learnt that link building involves the same skills as media relations. And this means that the relationship must come first. Because who even opens an email (or answers a phone call) from a stranger, let alone acting on the contents of that message?

Something similar has been happening, in an even more compressed time frame, with influencer marketing.

First, it was identified as the new thing. Then the California gold rush followed: brands threw money at the opportunity on the inflated expectation of massive rewards. Influencers used every available trick to inflate their numbers in the expectation of untold riches.

The result is cynicism: another example of the fake news phenomenon. The point about influencers is that they’re influential when we know, admire and trust them. Once that trust is eroded, so their influence is diminished.

We’re reaching a perfect storm. Author Seth Godin explained just such a problem two decades ago: ‘The less it works, the more it costs. The more it costs, the less it works.’ He was describing advertising, but as consultant Scott Guthrie has pointed out several times this year, what passes for influencer marketing should be more accurately called influencer advertising.

Where is this leading us? Predictions are risky, but I anticipate that, as with SEO and with media relations, people will come to recognise the value of relationships over transactions. Over time, disciplines that started out as separate entities will be seen as the same thing.

In other words, public relations will regain a role in influencer marketing: the name may already be lost, but the discipline is there to be won.

Looking ahead, I can imagine writing a similar article to this at the end of 2019 but with a focus on community building.

Communities share a common interest or purpose. It takes no great leap to see why that will be more important than ever in 2019.

But communities are also fundamentally voluntary. If influencer marketing has become corrupted by money, the challenge with community management is to find the space and create the conditions where people will willingly give of their time and expertise for free, for no other reward than being recognised as a valued contributor to that community.

With that spirit in mind, let me award some meaningless gongs to those in our community who have inspired my thinking, and who have given their thoughts away for free.

On influence: In her Power and Influence blog, Ella Minty writes about the larger forces at work. Scott Guthrie has explored the ups and downs of influencer marketing in forensic detail throughout the year, supported by Stephen Davies and Orlagh Shanks.

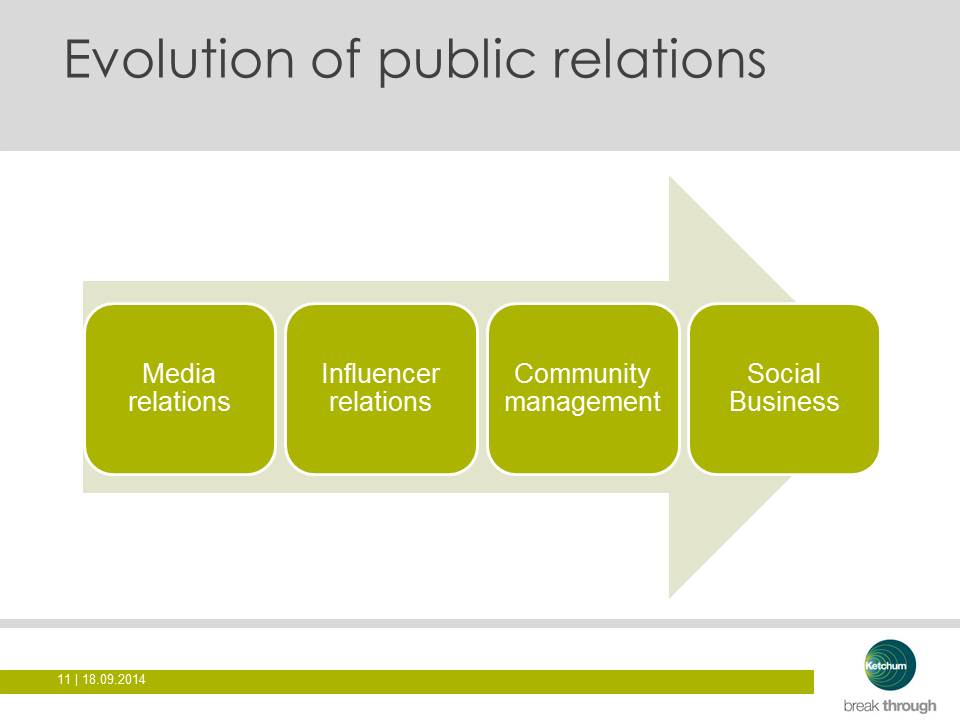

On media relations in the digital age: Stephen Waddington is my guide – and I still use his model of public relations evolving from media relations through influencer relations and on to community management in my teaching.

On community: author and consultant Richard Millington is the expert, though US scholars Kruckeberg and Starck conceptualised public relations as community building thirty years ago (that’s long before social media, before even the worldwide web).

This reminds us that while we need to be current with what’s changing, we should not lose sight of the more fundamental principles and concepts. Brands and businesses are run by people. Influencers are people (or are built by people). Consumers are people, and they have agency too. Just as we’re no longer defined only by our work, we’re not defined merely by what we buy.

Marketing may be big. It may be important. But is seems to me to provide a very narrow world view. More consumption is not the answer to every problem: it took the issue of single-use plastics to bring this to the fore in 2018.

Public relations should be well placed to help organisations cope with uncertainty and diminished trust. To understand that there’s more to relationships than money, that the customer may not be king. That’s my hope for 2019.