Review: Crisis Communications

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

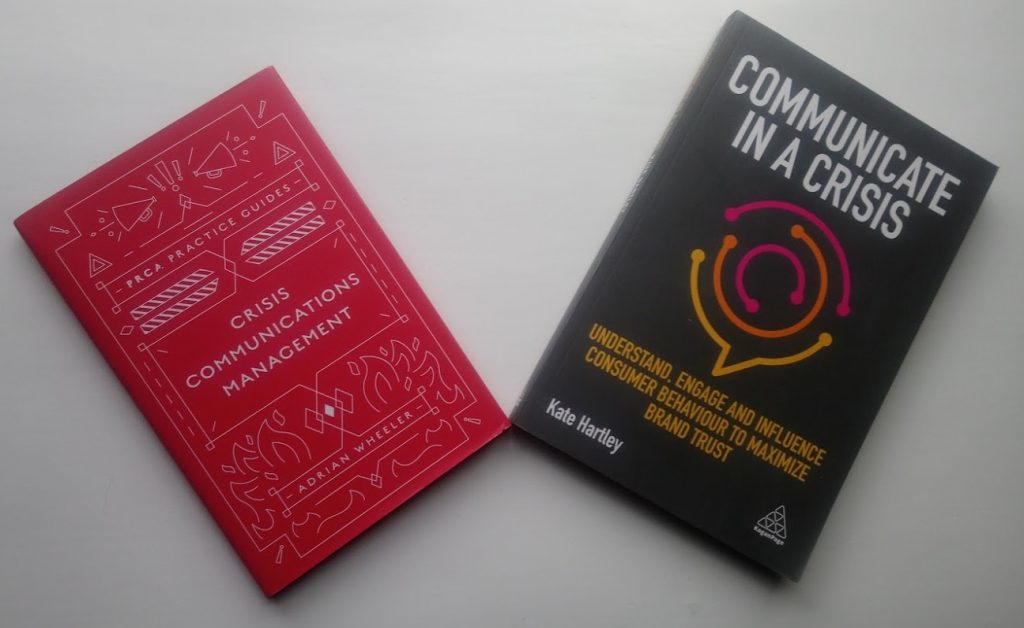

Crisis Communications Management

Adrian Wheeler

PRCA Practice Guides / Emerald, 2019, 134 pages

Communicate in a crisis: Understand, Engage and Influence Consumer Behaviour to Maximize Brand Trust

Kate Hartley

Kogan Page, 2019, 237 pages

It certainly feels as if we’re living through a crisis, though it may be more accurate to describe the coronavirus pandemic as an emergency. But this seems a good time to review two recent practitioner books on this topic.

Adrian Wheeler is a well-known public relations consultant and trainer. This addition to the pleasingly dinky series of PRCA Practice Guides takes the distinctive stance that while you may know what a crisis is, why it matters and how it should be handled, your boss or client is unlikely to. So the book presents the arguments you can use with them around preparing for a crisis and handling one when it happens. As Wheeler reminds us of the likelihood of a crisis in the social media age, ‘it’s no longer ‘if’ but ‘when’.’

He provides a primer that many will find useful, but I’m uneasy with the rather pat advice that ‘the option of doing nothing and saying nothing is not an option.’ Sometimes, in a world of fake outrage and misinformation, it’s best not to feed the trolls. What about ‘keeping shtum’ (Steven Olivant) or strategic silence (Roumen Dimitrov)? What about Tony Langham’s warning (in the same series) that ‘if communication did not cause the problem, it cannot fix it’?

But there’s much that’s useful here to a public relations or corporate comms practitioner who may be encountering their first crisis. You may find yourself working with lawyers for the first time, and their point of view may differ from yours. They may be more risk averse, but the argument that ‘lawyers are not paid to protect reputational assets’ feels outdated, certainly when you consider the way Schillings describes its services.

This is a small book, with short chapters, and the author has attempted to cover the basics while avoiding complex arguments. So it may appeal to many. It’s a useful guide, strong on the basics and with some practical checklists, though I recommend the more analytical and broad-ranging approach of Andrew Griffin’s Crisis, Issues and Reputation Management published in 2014.

There are many books published on this topic including from academics. So why did Kate Hartley, co-founder of crisis simulation training company Polpeo, feel that another book was needed? Her focus is less on what companies should and shouldn’t do in a crisis, but on how consumers react. She’s interested in the psychology of crises even more than in the processes involved.

But it’s not just consumers. She points out that our experience of Uber is shaped by its local drivers more than by its corporate comms team in the US; a supermarket by its checkout staff. So employees are also central to our experience of businesses.

It’s easy to forget about employees in a crisis, focusing instead on external audiences. But your employees will be at the front line of the crisis, answering questions from stakeholders, often fielding questions from media, and talking to friends and family about the situation outside of work. They will be the people who either support you through the crisis and defend your reputation, or damage it.

Hartley gives us five reasons why people are so quick to get angry with brands and explores this paradox: why people love to hate. ‘Social media has empowered everyone with an internet connection to express their views to, and be heard by, brands that break their psychological contract. Where people were powerless before social media, they now have power to influence a brand’s behaviour – or at least to make the brand sit up and take notice.’

If Adrian Wheeler has written a traditional book on crisis communication, Kate Hartley’s is contemporary. She addresses hoaxes and fake news – and asks why we fall for this stuff (‘these play to our fears, or to our hopes’). ‘Most people don’t stop to think about whether a story is true. With a declining trust in media sources, people seek out news that they instinctively believe, and they share it.’

She talks us through media consumption, influence, and the social media echo chamber. She discusses instant gratification: ‘In the age of Netflix and Amazon, we don’t have to wait for anything, anymore. If we want something delivered, we can get it from Amazon in an hour. If we want to watch the next episode of a TV series, we don’t have to wait a week, we can binge watch the whole series on Netflix… When we post to social media, we get instant feedback from our friends as they like, share and comment.’

This is important because it explains the context and complexity of crisis management: why people are so quick to get angry, why they expect an instant response, why numbers involved can escalate so rapidly.

This potential for escalation may lead you to feel that everything is a crisis. So how to identify a crisis from background noise?

‘Some crises are obvious (an accident, a death, a fire, a scandal, an outrage). Others creep up on you.’ Jonathan Hemus is quoted here saying ‘a crisis for a company is if an event renders you unable to conduct your core business.’

Continuing the focus on psychology, Hartley explores the way we respond to threats (to the often cited ‘fight or flight’ she adds the option to freeze). But how do you build personal resilience? How can you train for the unexpected? The case study of Captain Chesley Sullenberger, who landed his stricken passenger aircraft on the Hudson River in January 2009 suggests one answer. This modest man explained ‘for 42 years I’ve been making small regular deposits in this bank of experience: education and training, and on January 15, the balance was sufficient so that I could make a very large withdrawal.’ All 155 passengers and crew were saved that day.

Both of these books were published last year, before the novel coronavirus pandemic. Yet Hartley talks about how technology can be used to predict and track emergencies and discusses the use of data in the handling of the Ebola outbreak in 2014.

Fluently written and well-informed, it’s a surprising and distinctive book. The only disappointment, given how well sourced and authoritative this book is, was the very limited, apparently random and not very useful selection under ‘Further Reading.’

Take your pick. Wheeler gives us the nuts and bolts to construct a conventional approach to crisis communication; Hartley brings us up to date by adding in emotion and the impact of technology.