Disease awareness days

How do we cut through the noise to change behaviour?

About the author

Michelle Cammack prepared this article as part of a CIPR Professional PR Diploma assignment while studying with PR Academy.

Disease awareness days are now so common that many fall on the same day or month in the year[i] with some non-disease awareness days also competing for air-time on the same day[ii].

Each event tends to be supported by a creative communications campaign including outreach across all media, sometimes fronted by a celebrity. This means that on any given disease awareness day, audiences will receive multiple health-related messages, some conflicting, as they are generated from different sources – multiple pharmaceutical companies, Patient Advocacy Groups (PAGs) and charities.

With this continuous stream of noise, the content is at risk of being ignored, resulting in little engagement and limited behaviour change. We need to ask ourselves ‘What is the intent of these campaigns, other than awareness? Are they effective in helping the respective audiences – usually the public – to understand the risk factors or symptoms of a specific medical condition? More importantly, do they drive behaviour change, so that it prompts an action? Overall, is the extensive pharmaceutical company spending behind these single-day events making a difference?’

Disease awareness in a highly regulated industry

The UK pharmaceutical industry is regulated by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) Code of Practice.[iii] This Code prohibits promotion of prescription-only-medicines (POM) to the public in the UK via communications activities, specifically the media and cannot be included in disease awareness campaigns (DACs). This is reiterated by the 2020 UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Disease Awareness Campaign Guidelines[iv]. DACs can be conducted, providing the pharmaceutical company has a medicine in the therapy area that is being acknowledged[v].

Interestingly, from a public relations and marketing perspective, the metrics and evaluation currently aligned to these campaigns focuses on the ‘number of impressions’, or from a social media perspective, ‘downloads’, ‘likes’ and ‘shares’, which are immediate, rather than long-term. These metrics are only reporting the number of people who were exposed to the message. Research shows that people who are simply given more information are unlikely to change their beliefs or behaviour[vi], and they don’t immediately respond to emotional story-telling.

Robust evaluation is critical to assess whether objectives have been met and provides feedback that can be used to reorient or adjust activities, if the campaign was not exerting the desired impact[vii]. If companies commit to this evaluation, it may become clear that competing for share of voice on a specific day is not optimal.

We should stop just ‘raising awareness’

A recent article in Psychology Today echoes the sentiment that when awareness campaigns are everywhere, they may not be effective, as how can people act on something just because they have been made ‘aware’ of it?[viii] They can also have a ‘backfire effect’, where the approach of awareness or knowledge campaigns alone, can ‘backfire’ where the audience ignores the evidence and messaging as it contradicts a view point that they currently hold.

An example case study focuses on raising awareness about substance abuse amongst teenagers, which can lead to the perception that this is rampant in that population. This leads to a negative situation where teens perceive that their counterparts are abusing substances, which in fact is misperception and overestimation. The conclusion is that there may be ‘too much awareness’ and the approach need to be different when it comes to certain topics.

A more strategic communications approach should focus on a long-term messaging platform as change takes time. The campaign should have consistent messaging, reinforced at regular intervals, underpinned by a clear call-to-action, to avoid misunderstanding and misinterpretation.

Applying this insight to DACs, a more strategic communications approach should focus on a long-term messaging platform as change takes time. The campaign should have consistent messaging, reinforced at regular intervals, underpinned by a clear call-to-action, to avoid misunderstanding and misinterpretation. These strategies will help the audience to understand the message with more consistency, over a longer period of time: ‘little and often’[ix].

Similarly, the 2017 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, expresses the need for organisations and ‘activists’ to adopt a more strategic approach to public awareness campaigns, and echo the thoughts of Gorman et al: when campaigns focus solely on raising awareness, they can fall short and do more harm than good[x].

The psychological approach to generating behaviour change

This is best described by a communication theory known as the Information Deficit Model[xi]. The term was introduced in the 1980s to describe a widely held belief about science communication – that much of the public’s scepticism about science and new technology was rooted, quite simply, in the lack of knowledge. If the public only knew more, they would be more likely to embrace scientific communication.

However, research shows us that people progress through different stages of change, including:

- Pre-contemplation: people are unaware that they have a psychological problem

- Contemplation: people consider how to make a change in behaviour

- Action: people modify a change in behaviour[xii]

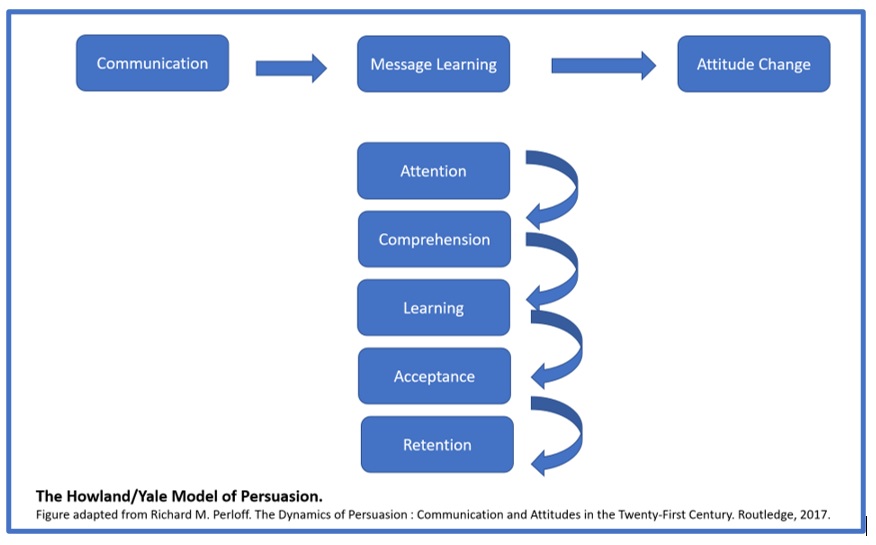

As illustrated in the Figure below, researchers Howland and the team at Yale University were interested in understanding why messages changed attitudes, with a focus on learning and motivation. Persuasion entailed learning message arguments and noted that attitude change occurred in a series of steps. In order to be persuaded, people had to attend to, comprehend, learn, accept and retain the message, before behaviour change was observed[xiii]. This takes time.

Creating longer term campaigns that lead to action

Research has identified a number of steps that should be taken in order to maximise the likelihood of success, including audience segmentation and tailored messages. Efforts should be co-ordinated across media, and messages repeated over time, remembering that it is sometimes easier to promote a new behaviour, than to convince people to stop a dysfunctional behaviour.[xiv]

Another consideration, with DACs is that they need to be flexible, adapt to the environment and to build on their story[xv].The University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications is building an academic discipline called ‘Public Interest Communications’[xvi]. This is defined as ‘the development and implementation of science-based, planned strategic communication campaigns with the goal of achieving significant and sustained positive behavioural change or action on an issue that transcends the particular interests of any single organisation’.

A case study: Bowel Cancer UK

A UK-based PAG, Bowel Cancer UK’s awareness campaigns are not reliant on specific disease awareness days or months. Following their recent campaign, spearheaded by their Patron, Dame Deborah Jones, the PAG has acknowledged that ‘without doubt [she], saved lives because of her openness and honestly about her own diagnosis and experiences, which has forever changed the way people talk about bowel cancer’. Deborah was regularly visible across many communications channels, leading a BBC Podcast: You, Me and the Big C, and particularly active on Twitter with her tag @Bowelbabe[xvii].

The organisation recently launched their #GetOnARoll campaign in conjunction with several supermarkets in the UK, with a call-to-action written on toilet rolls. An example of an evolution of messages and a campaign with ongoing momentum[xviii].

The future of long-term public interest communications campaigns

Based on research[xix], and looking at a more strategic long-term solution, as companies plan the next phase of DACs, there are essential elements that underpin a successful public interest communications campaign:

- Segment and target your audience: identify your target audience (which sub-set of ‘the public), specifically the individuals or groups whose action or behaviour change will be most important to help you achieve your goal, perhaps based on demographics or age

- Create compelling keys messages with a clear call-to-action: craft campaign messages, stories, and a call-to-action that does not threaten an audience. Research into how your target audience forms opinions and who influences them

- Develop a theory of change: a road map of how you will achieve change – what do you want your audience to feel, think and do? Building a strong theory of change requires: a clear goal, a clear understanding of what will be different and what will cause it to change, and an understanding of what will influence people to act.

- Use the right channels and ‘voice’ or messenger: in order to inspire and persuade people to adopt a new behaviour or a new way of thinking, having the message come from people who have authority and credibility in your audience’s world matters (for example @Bowelbabe).

- Partner with a patient organisation: many PAGs will be sharing messages at the same time, so work together for greater impact

- Evaluate: conduct robust evaluation to assess whether your objectives were met and use this feedback to refine your future activities

Below is a quote from a recent blog from The Financial Brand, commenting on the number of times an audience needs to hear a message before they register it: “marketing experts like to debate the ‘right ways’ to calculate effective frequency. Some say repeating a message three times will work, while many believe the ‘rule of seven’ applies. A Microsoft study investigating the optimal number of exposures required for audio messages, concluded between six and 20 was best”[xx].

Disease awareness days still have a role

Disease awareness days are still valid. However, they should add value to the evolution of a broader ‘public interest campaign’ with a call-to-action, to prompt an action. In addition, as a longer-term communications strategy is mobilised, an awareness day should provide another opportunity to share your campaign, rather than the only opportunity.

In this way, campaigns will cut through the noise and ultimately contribute to a change in behaviour.

Sources of information

[i] List of awareness days | UCL Human Resources – UCL – University College London. www.ucl.ac.uk/human-resources/wellbeing-calendar. Last accessed 5 July 2022.

[ii] Awareness Days in United Kingdom in 2022 | There is a Day for That!. www.thereisadayforthat.com/united-kingdom. Last accessed 7 July 2022.

[iii] www.abpi.org.uk. Last accessed 7 July 2022

[iv] Appendix_7.pdf (publishing.service.gov.uk). www.mhra.gov.uk. Last accessed 7 July 2022

[v] 2021-abpi-code-of-practice.pdf (pmcpa.org.uk). Clause 26 and 27. Last accessed 7 July 2022

[vi] Christiano A. Neimand A. 2017. Stop Raising Awareness Already (ssir.org). Last accessed 12 July 2022

[vii] MLA 9th Edition (Modern Language Assoc.). Richard M. Perloff. The Dynamics of Persuasion : Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2017. Chapter 14: Health Communication Campaigns. Last accessed 19 July 2022

[viii] Gorman S. Gorman J. 2018. Does Raising Awareness Change Behavior? | Psychology Today. Last accessed 12 July 2022

[ix] Gorman S. Gorman J. 2018. Does Raising Awareness Change Behavior? | Psychology Today. Last accessed 12 July 2022

[x] Christiano A. Neimand A. 2017. Stop Raising Awareness Already (ssir.org). The Stanford Social Innovation Review. Last accessed 12 July 2022. (SSIR is published by the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, at Stanford University)

[xi] Information deficit model – Wikipedia. Last accessed 12 July 2022

[xii] MLA 9th Edition (Modern Language Assoc.). Richard M. Perloff. The Dynamics of Persuasion : Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2017. Chapter 14: Health Communication Campaigns. Last accessed 19 July 2022

[xiii] MLA 9th Edition (Modern Language Assoc.). Richard M. Perloff. The Dynamics of Persuasion : Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2017. Chapter 14: Health Communication Campaigns. Last accessed 19 July 2022

[xiv] MLA 9th Edition (Modern Language Assoc.). Richard M. Perloff. The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2017. Last accessed 20 July 2022

[xv] Perloff RM. The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2017. Last accessed 20 July 2022.

[xvi] Home – UF College of Journalism and Communications (ufl.edu). Last accessed 20 July 2022

[xvii] Home | Bowelbabe Fund www.bowelbabe.org. Last accessed 20 July 2022

[xviii] Our #GetOnARoll campaign | Bowel Cancer UK. Last accessed 20 July 2022

[xix] Christiano A. Neimand A. 2017. Stop Raising Awareness Already (ssir.org). Last accessed 12 July 2022

[xx] Say It Again: Messages Are More Effective When Repeated (thefinancialbrand.com). Last accessed 20 July 2022