Fake news: how to solve a ‘really wicked problem’

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

‘Amongst many other things, academics give us frameworks and critical thinking’. This was Dr Nicky Garsten of University of Greenwich welcoming us to virtual Mind The PR Gap 2020.

She was responding to Dr Kevin Ruck of PR Academy who had restated the original purpose of Mind The PR Gap – to bring researchers, academics and practitioners together to share thinking.

Yet the academic approach rewards reason, deliberation and evidence. Today’s Mind The PR Gap session raised the intriguing challenge of how to understand, incorporate and respond to emotion – often emerging at the speed of a tweet.

Professor Vian Bakir of Bangor University referenced Ulrich Beck’s concept of the risk society and argued that Covid-19 is a classic example because of the uncertainty and the risk to death.

‘We have to respond to risk without adequate knowledge. We just don’t know.’ This example of an ‘uninsured society’ (Beck again) is a challenge to policymakers and government communicators.

In our post-truth universe, objective facts are less influential in public opinion than emotions.

So much for experts and evidence. She went on to argue that ‘when health messages are ambiguous, people are less likely to change their behaviour’ and was critical of the Dominic Cummings affair, saying that lying in public was a breach of the principles of good public communication.

Earlier, her university colleague (and life partner) Professor Andrew McStay had given a rather more optimistic summary of the connection between emotions and technology (‘emotional AI’). This may sound troubling and dystopian but he cited scientific antecedents dating back to the nineteenth century and also discussed some positive developments such as the tracking of drivers’ emotions and concentration levels for future in-car safety features.

Clearly, there are ethical issues around surveillance and the collection of personal data, and he was keen to open up the question of reputational issues facing technology companies in this area. He framed the whole issue as one of collective rights.

Influence was a central concept.

If we can influence emotions, we have a better than average chance of affecting cognition.

His advice to those in public relations was to ‘understand the technologies, but also to tell positive stories about companies trying to do the right thing.’

The expert panel, chaired by Philip Young and Ann Longley included consultants Stuart Bruce and Kevin Read and Stuart Youngs from insights business Texture AI.

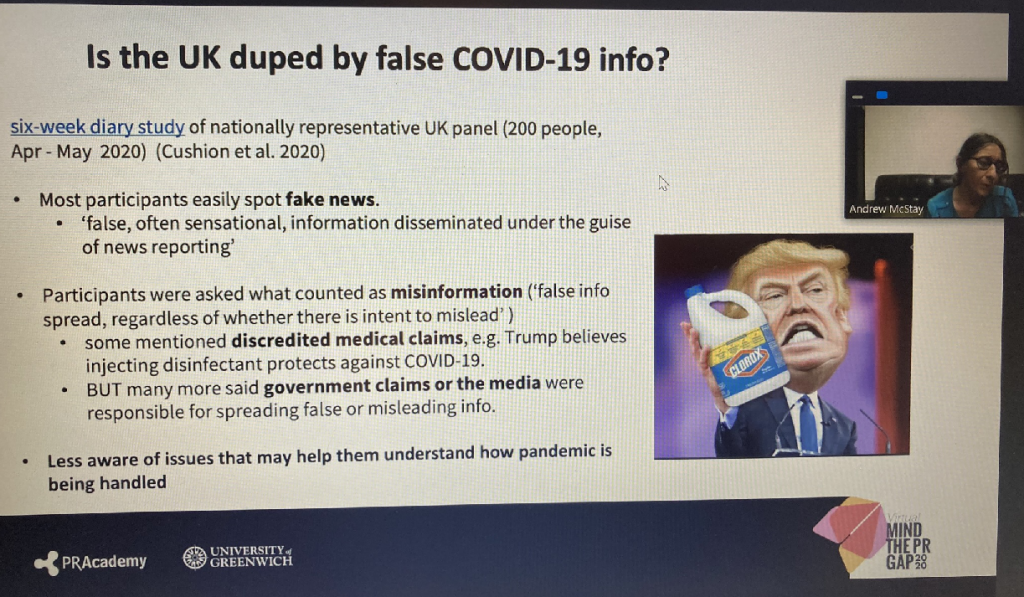

Among the contentious topics raised was the question of conspiracy theories and the rejection of expert opinion seen for example in the rise of anti-vax sentiment. Philip Young indicated a divergence between those receiving their news from the mainstream media compared to those receiving their news from social media such as Facebook.

Vian Bakir had earlier indicated that trust in mainstream media was twice as high as trust in social media. ‘60% of people think that the news media have helped them understand the extent of the crisis. We all want more information and the news media are doing a good job at providing this. You can’t get away from the fact that this is a risk issue. I think this is what is called a ‘really wicked problem’ in the bad sense of the word.’

And yet the conspiracy theory linking conoranvirus to 5G infrastructure persists.

‘The risk society shifts from indifference to hysteria and vice versa’ said Bakir, citing Beck.’This hysteria is precisely what governments want to avoid. We all remember the panic buying of toilet roll earlier, and now I wonder if we’re moving more towards indifference’ she said, citing the much lower usage of facemasks in the UK than in other countries.

‘Governments are instructing their citizens to engage in profound and rapid behaviour change: they’ve asked us to cut physical contact; not to go to work; not to go to school. This is a really big problem for government: how to get people to comply with profound behaviour change while maintaining public trust in a risk issue full of uncertainty in what many people think was already a post-truth universe.’

Post-truth: relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’ (Oxford Dictionary).

We’re back tomorrow for a session focused on careers and professionalism. I hope to see you there.

Read our write up of day 2 of Mind the PR Gap 2020: The Future of Work