Issue management in public affairs

About the author

Our guest authors are what make PR Place such a vibrant hub of information, exploration and learning.

Coca-Cola case study

Guest author: Dr Conor McGrath

Strategic planning in public affairs fundamentally concerns two key elements – developing plans by which public policy issues can be managed, and then communicating those plans to Government.

Chase and Crane (1996, p. 138) offer a thoughtful call for companies to pay equal attention to “strategic profit planning” and “strategic policy planning”. It is in an organisation’s issue management that both these existential functions are integrated.

While there are nearly as many definitions of issue management as there are academic articles on the subject, several basic features which demand attention by practitioners are clear.

First, issue management has to be concerned with identifying potential issues which could impact upon the organisation – this is the essential precondition to all else, as if an issue evades detection then nothing can or will be done about it.

Second, it is necessary to prioritise issues in terms of the extent to which they could matter to the organisation – the more important the issue is to the organisation (or what researchers term the issue salience), the more likely the organisation is to engage in political activity intended to influence the outcome. The rational organisation will further prioritise issues in such a way as to only focus on those which are not merely important but also which are most likely to be influenced effectively – in other words organisations should concentrate on those issues which are critical to their strategic objectives where the organisation’s input will make a material difference.

Third, there is little value in identifying issues unless the process then goes on to set objectives, formulate a plan of action in respect of each, and implement and evaluate that activity. Here the organisation is arriving at its own internal policy position on the issue.

And, fourth, issue management must involve the organisation in attempting to influence public policy since each significant issue will become important not just to the organisation itself but also to its stakeholders in government, regulatory agencies, pressure groups, public opinion, and so on.

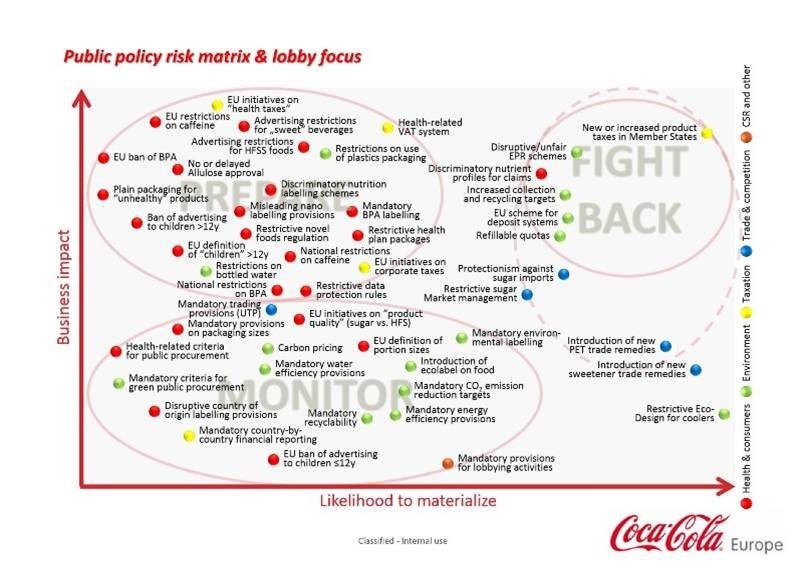

While we don’t often get this sort of detail about internal planning from major organisations, in 2016 a whistleblower leaked a set of documents relating to Coca-Cola’s public affairs strategy. The graphic below shows their thinking about policy issues in the EU, and was actually developed by a senior manager for EU government relations.

The far right hand side of the diagram shows that all policy issues have been categorised into 5 colour-coded agendas: red for health and consumers; green for environment; yellow for taxation; blue for trade and competition; and orange for CSR and others.

The horizontal axis shows Coca-Cola’s expectation of how likely each issue is to be implemented, while the vertical axis assesses the potential impact of each issue on the company’s operations.

Issues have further been classified into three groupings, by which Coca-Cola prioritises them: monitor (for issues least likely to happen and least likely to affect the business); prepare (for issues which aren’t likely to pass but which would have a significant impact); and fight back (for those issues which are both likely to materialise and likely to have a serious impact on the firm).

Several elements of this diagram are striking. To take the negatives first, most of the issues Coca-Cola was then considering relate to health and consumers (the red dots), but only one of these was thought to be relatively likely to actually happen – that is a criticism more of the EU system than of the company.

Similarly, most of the trade/competition issues were thought relatively likely to be enacted, but none were deemed likely to have significant impact on the firm. While most environmental issues were thought unlikely to happen, four out of the six issues Coca-Cola intended fighting actively relate to increased environmental regulation.

Another is about the labelling of its products. But clearly out on its own in the top right corner – both very likely to happen and having a substantial effect on the company’s business – was the issue of a soda tax in the EU. It is, finally, revealing that the top priorities are placed in a category called ‘fightback’ – Coca-Cola’s public affairs team in Brussels prioritised only issues which were negative from the firm’s perspective, and were not actively pushing any positive policies.

More positively, though, whether one likes Coca-Cola as a company or not, it obviously takes issue management seriously and thinks about it in a professional and strategic way. And this diagram does provide a template for how other organisations could visualise their own issue management in a comprehensive and clear manner.

Reference

W.H. Chase and T.Y. Crane (1996) Issue Management: Dissolving the Archaic Division Between Line and Staff In: L.B. Dennis (ed.) Practical Public Affairs in an Era of Change: A Communications Guide for Business, Government, and College. University Press of America: Lanham, MD; 129-141.