Review: F**k Business: The Business of Brexit

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

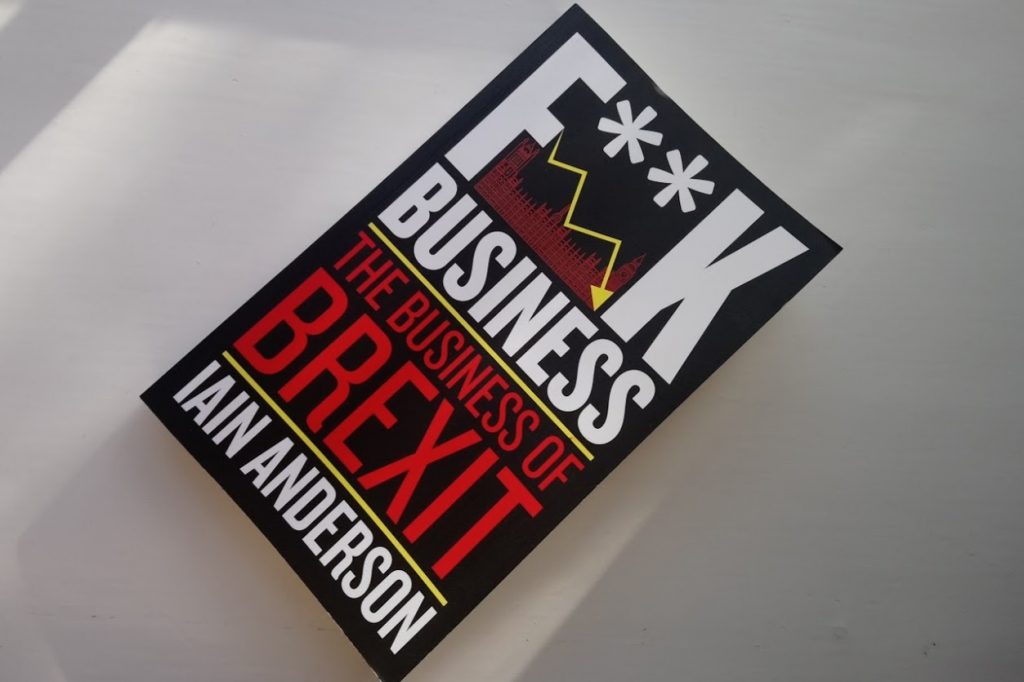

F**K BUSINESS: The Business of Brexit

Iain Anderson

290 pages, Biteback Publishing, 2019

‘No trust left’

All good business books set out to answer a pressing question. And this is an important one: how did a supposedly business-friendly Conservative party set itself on the other side of the argument from most business leaders and organisations?

Who better to answer this than Iain Anderson, a Conservative insider who voted Remain but who has accepted the result of the 2016 referendum. As a lobbyist he sees his role as an intermediary between business and politics. Some job!

Nor is it a question with a simple binary answer (is it ever?). He recognises that there are prominent entrepreneurs who have been cheerleaders for exiting the European Union. But this isn’t a book about the details of trade and tariffs, immigration or regulation. It’s a book about politics.

That sometimes means policy, but mostly it involves people and the decisions they take, sometimes on principle but more often as a pragmatic response to circumstances.

So it’s also a story of two elections (in 2010 and 2015) and two referendums (in 2014 and 2016). David Cameron and Theresa May are central to the story; Boris Johnson less so (despite being quoted in the two word title) as the book was written in the first half of 2019.

Cameron had unexpectedly won a majority in 2015, so had a mandate to call the referendum and renegotiate Britain’s relationship with the European Union before backing Remain. Yet this was the same David Cameron who a decade earlier had removed the Conservative Party from the European People’s Party coalition that included Angela Merkel’s CDU.

It’s not just about Cameron (who is treated kindly by Anderson). The election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader made it easier for the Conservatives to become a pro-Brexit party because most businesses had an even greater suspicion of his agenda.

But it is all about Conservative politics. Where is Nigel Farage in this story? He gains just two fleeting mentions.

The same chronology is covered with more forensic detail in Sunday Times political editor Tim Shipman’s books All Out War and Fall Out. But I enjoyed the subjectivity in Anderson’s telling: he places himself throughout the story. We learn about his politics – he’s Scottish and Conservative, and went to the same Aberdeen school as Michael Gove; he’s been friends with fellow Aberdonian Craig Oliver since university. We learn about his husband, about his relationship with his parents who still live near Aberdeen. Above all, we learn how well connected an effective public affairs operator needs to be.

This is an anecdotal, even gossipy, book – but that makes it a good read. Here’s Anderson commenting on the launch of the Stronger In campaign before the 2016 referendum:

How do you think that went?’ [BBC politial editor Laura Kuenssberg] asked me. ‘A bloody disaster’ was my response. Then we sat equally bewildered as top City spinner and Remain campaign grandee Roland Rudd invited what appeared to be his family onto the stage, where they all sat on the set while the tabloid snappers took photographs of them like the royal family posing for a rather relaxed wedding portrait. Laura and I looked at each other in disbelief.

Top city spinner indeed! Here’s another example of when he slips into airport bestseller writing style: ‘[Will] Tanner is a very tall figure and was easy to spot in the crowded, gilded IoD reception room in the heart of London’s clubland on Pall Mall.’ Surely he can’t have involved a ghost writer, can he?

More likely, given the hectic schedule he describes, it was partly written in airport lounges. This is a genuine insider’s account, and where it tells a fresh story is through its focus on the services sector that dominates the UK economy, and above all financial services. Most of the political debate revolved around goods and Northern Ireland border checks, yet the status of London as Europe’s financial capital has attracted less attention.

In 2018, Anderson’s own firm Cicero decided to set up shop in Dublin. ‘There were many reasons for that choice, but the key one was the preponderance of our clients moving operations to Dublin to be ready for Brexit.’ (Elsewhere, he notes that Jacob Rees-Mogg had taken the same decision, for the same business reasons.)

And that’s one positive from the political turmoil. ‘At Cicero, we had seen our business grow over 20 per cent by the end of 2016… as it became clear there was a huge appetite for political risk analysis. Uncertainty, sadly, was rather good for business.’

Where the narrative was clear at the start and has become so again since the book was written (thanks to another Johnson slogan – ‘Get Brexit Done’) it’s surprising how indistinct the story became during the May years, the very recent past. The key theme is loss of trust: between the the prime minister and her cabinet colleagues, between government and parliament, between politicians and business, between parliament and the public.

To the mistrust between politicians and business, Anderson observes:

I am often asked by pro-Brexit politicians why business remained so wedded to the EU passport and was not willing to embrace the new opportunities. The answer remains simple. Business can only operate within a known and secured legal and fiscal regime.

Perhaps there’s another positive lesson to take from this. Ever since the Clinton and Blair eras, we’d assumed that globalisation meant that national leaders and parliaments had limited autonomy. As a result, politics had felt largely pointless and people came to feel disillusioned and disempowered.

Now we know that politics matters and just as emotion trumps reason in campaigns, political decisions can trump financial and business interests. It’s not (all) about the economy, stupid!