The comms and key workers question

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

Are you a key worker?

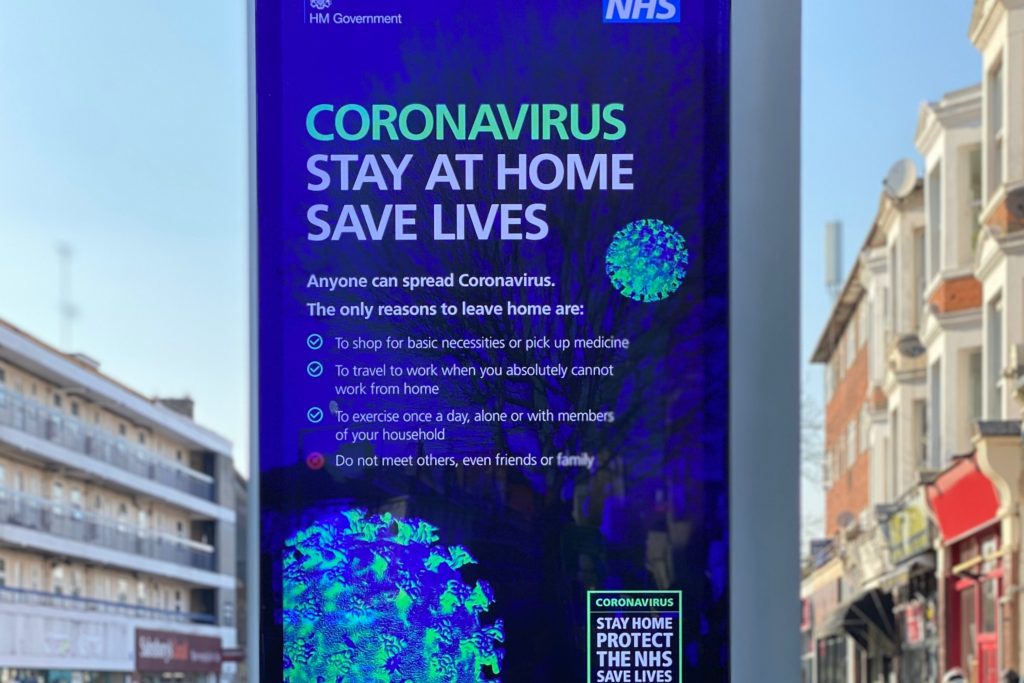

The lockdown has led to a formalisation of the concept. These are ‘people whose jobs are vital to public health and safety during the coronavirus lockdown.’ Key workers are encouraged to go to work, while all the rest of us are required to work from home as best we can.

The government has published its list of sectors critical to the COVID-19 response, and comms professionals are not included, except in some limited areas of the public sector:

Local and national government

‘This only includes those administrative occupations essential to the effective delivery of the ‘COVID-19 response.’

Public safety and national security

‘This includes police and support staff, Ministry of Defence civilians… fire and rescue service employees (including support staff).’

Clearly, these are exceptional circumstances. But this challenges us to rethink how vital our roles are, and how essential a service is provided by public relations and comms practitioners.

We all like to think what we do is important, or why would we go to work? Textbooks and academic definitions provide plenty of reassurance of the elevated status of the role. AMEC has taken the lead in giving us tools to assess the value of comms. But the current crisis asks a very stark question of each of us, and the lockdown gives us plenty of time to reflect.

I asked some PR Academy colleagues for their experiences of how central the comms role was, particularly in a time of crisis or when working on key projects – and share mine below.

Ann Pilkington

Some people may scoff at the idea of PR people being key workers but it depends what we mean by PR.

Many who work in communication (and may have the title PR) for emergency and public services will be accustomed to taking part in multi-agency, major incident scenario planning. Otherwise, who is going to ensure the media and other stakeholders are kept informed, who is going to monitor what people are saying or asking and help the organisation to respond? Who ensures that the CEO is well briefed with the correct facts before attending a press conference? Who sets up the press conference?

I worked as a press officer in financial services during “Y2K” – the cut over from one millennium to another. Those old enough will recall the fear that computers would stop working because they hadn’t been programmed to take account of years beginning with 20 not 19. For banking it was compounded by extra public holidays meaning the banks would be closed for longer. Would they be able to keep the cash machines topped up? (Cash was still king back then.) It was a critical project and PR people were part of it. We had major incident table top exercises, media practice for key spokespeople, press teams were called up to the Financial Services Authority (as it was then) for briefings and many of us spent that New Year’s Eve sober and on call.

But it’s not just those working with external stakeholders that have a role to play.

In any major incident or crisis (and they are different things) ensuring employees know what is happening and what it means for them is paramount. We see this more than ever in the current situation.

Many will be worried about their jobs, furloughed, working remotely for the first time, or in a role which means implementing new measures to protect their health and safety as well as that of customers.

PR also has a role to play in influencing policy decisions. Communicators should not be there just to deliver the message however flawed they think it is. I don’t know if any PR practitioner was involved in the message sent from Mike Ashley owner of Sports Direct to reassure us all that he would be staying open. But I would like to think that there was some PR-led common sense in the subsequent apology and support offered to the NHS. Of course it isn’t always easy to have influence, you need to be in an organisation that is willing to listen and we have seen from some responses to this pandemic that not all are.

Chris Tucker

As with Ann my first brush with Crisis Communications at a senior level was with Y2K or the so-called Millennium bug. I was heading up Business Banking PR for Barclays but had also been given the role of PR lead on the preparations for Y2K. The role had seemingly gone on for years and had almost become business as usual. I was then shocked beyond belief when in the run-up to the day itself I was given a letter signed by the then Metropolitan Police Commissioner saying I had the authorisation on the day itself to travel freely across the City to wherever I was needed. I am kicking myself I did not keep it as a souvenir.

Having since studied Crisis Communications from an academic point of view I can see at a high level what my role would have been if the worse was to have happened. When a crisis hits it creates a vacuum so real it can almost be felt. Normal activities largely cease and stakeholders, especially internal stakeholders, await instructions from the leadership team. That leadership team is going to need to some help to disseminate those instructions widely and at speed. It is the communications team that knows best how to do that.

However, that is largely a technical role and given the amazing platforms we now have – Zoom, Microsoft Teams etc. to work collaboratively and how many internal and external communications channels have now moved online, we can see how the communications levers can be pulled remotely. As long as our organisations are willing to embrace the new WFH reality (and some are doing so quicker than others) we should not have to be in the office to perform this part of our role. But as we know there are many other facets to the PR leader’s role.

Professor Anne Gregory and Paul Willis illustrate this well in their book Strategic Public Relations Leadership.

Gregory and Willis talk about the senior PR leader’s role as to some extent holding up a mirror to the organisation. It is the PR leader’s role to articulate the views of all stakeholders and make sure they are heard; to speak truth to power even when it is uncomfortable; and to ensure the organisation acts according to its values – even in a crisis.

This is much more of a strategic role and that is much harder to do effectively from home. Nowadays it seems many organisations are more likely to want someone performing this type of role near to where the decisions are being taken. I believe it is a demonstration of how far the PR profession has come.

Richard Bailey

In the good times (remember them?) the often-used phrase ‘it’s PR, not ER’ was a cheerful reminder not to take ourselves too seriously. While we may not be life savers, we’re probably not responsible for the loss of life either.

I always took this phrase as a gentle rebuke, though. That’s because I recall being taken on hospital ward rounds on Christmas Day by my consultant father. He loved his work, and rarely seemed to take time off. My two sisters became doctors while I followed my mother and have variously worked in publishing and teaching.

So each time Christmas comes around, with the inevitable hiatus in my work stretching to beyond New Year, I feel a pang of guilt that my work has never been so important, so vital to life, as to require my presence on Christmas Day.

I’m not alone in this. I remember when I first went up to university there was a final year student who was much more celebrated than any other. Hugh Laurie – famous then for representing our unfashionable college in the Cambridge crew for the annual boat race. He’s since had a much more stellar career as a comic and serious actor, and yet another as a musician. And yet, I read, he too feels similar guilt that his work has not amounted to as much as his GP father’s.

I’ve signed the Official Secrets Act. I’ve been on call at evenings and weekends, and have been the communications lead on incidents involving nuclear radiation. But I’d say these were health and safety issues rater than matters of life and death.

As a lecturer, I visited the Royal College of Physicians and opened their box files of archive papers relating to their first ever press conference. It was Ash Wednesday, 1962, and it marked the launch of the global health campaign against smoking. It linked my father’s work to mine, and was a reminder of how communication campaigns can make a difference – though it’s sobering that this one took decades before it could claim success.

I hope to have added value to my clients and employers; I hope I’ve made a difference to some of my students. But key worker? Leave me at home.