A year of learning virtually

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

On 16 March 2020 I posted two messages to the online site of the university module I was teaching. The first spoke about my plans for a staged shift from classroom to online teaching; the second, responding to new government instructions issued that day, confirmed that the change would be much more abrupt.

I’ve not taught a face-to-face class in the year since then.

Like everyone else, I’ve been forced to adapt. But this piece is not about online teaching; rather, it’s about online learning. It’s about the behaviour of learners, and the experiences we’ve all had as receivers of learning at the virtual events that have taken place in the year since then.

In October 2020 we welcomed new students at the university. There had been fears that many would choose to defer, but student numbers have been surprisingly robust (perhaps many came to realise that their alternatives to university – work, travel – were also going to be constrained during the pandemic).

Class attendance has been higher than I have come to expect from first year students (oversleeping, delayed buses, even outfit anxiety are no longer available as excuses for missing class since students can wake up and login without leaving bed.) PR Academy has also seen an upturn in candidates starting professional courses during the past year – perhaps as a positive response to job uncertainty.

Then, when it came to the first assignment deadline, submission rates were higher and so was the pass rate. In previous years, word has quickly got out that first year ‘does not count’. Technically – though not educationally – this is true since first year grades do not count towards final degree classification.

It would appear that one welcome response to the lockdown has been to make students more studious.

Plus there are upsides to being a student in the past year: many have saved on travel and accommodation costs, and it’s been good for widening participation since there are fewer barriers to education when all you need is an internet-enabled device.

That’s one narrative. It took me longer to realise the counter-narrative. That while participation rates may have been higher, engagement rates have been lower. My students have found it easy to log-in, but have been reluctant to switch on cameras, unmute their microphones and join in as they would have done in a conventional classroom.

You will probably be wondering why I didn’t require cameras to be switched on as part of the ground rules for our class. Well, some students will have notified the university about their additional support needs (again, part of the diversity and inclusion issue), and we educators have come to learn that you can’t assume that people are all able to participate in the same way.

Then there are the distractions: not everyone’s living arrangements are as conducive to concentration as we would wish; not everyone is ready for their lack of attention to hair, makeup and clothes to be exposed – and some may indeed still be in bed.

So having struggled not with participation but with class engagement, I conducted an experiment in one of our last sessions, a class based around the theme of curiosity. For one hour, a colleague they’d already met joined us to answer any questions from the class (any personal, professional or education-related question). The students could put their hands up and speak, or simply type their questions in the chat box. It wasn’t the most fluent hour, despite the efforts of my very open and chatty colleague. It’s just that the questions were rather stuttering and not very probing. I was forming the conclusion that students are willing recipients of education, but not active seekers after learning.

For the next hour of the same class, I set a writing task. The students were to write a short blog post on the topic ‘I’m curious’ and send it through to me. The results were pleasing to me – and evidently surprising to students not used to being set ‘vague’ assignments.

I then asked the class where they felt they had better demonstrated curiosity: in the real-time chat or in the writing exercise? All but one of the class members agreed with me that they had expressed themselves better in writing.

I should be happy with this level of literacy and this ability to express ideas in writing. University rewards those who can write – as does the world of public relations.

And yet… What if we’re producing a generation of introverts who are more comfortable communicating behind a screen and keyboard? What if we’re not equipping them to conduct real-time conversations? How would that prepare them for working in public relations?

I posted a summary of these thoughts on LinkedIn and there were a range of responses. One thought I was being alarmist; young people are resilient, and they will bounce back. Others have noticed a similar pattern.

I’ll go further: I think it’s a generational change. Young people are now so used to navigating almost all their relationships through their devices that even using the phone for its original purpose is becoming unfamiliar. Face to face contact with strangers can cause anxiety.

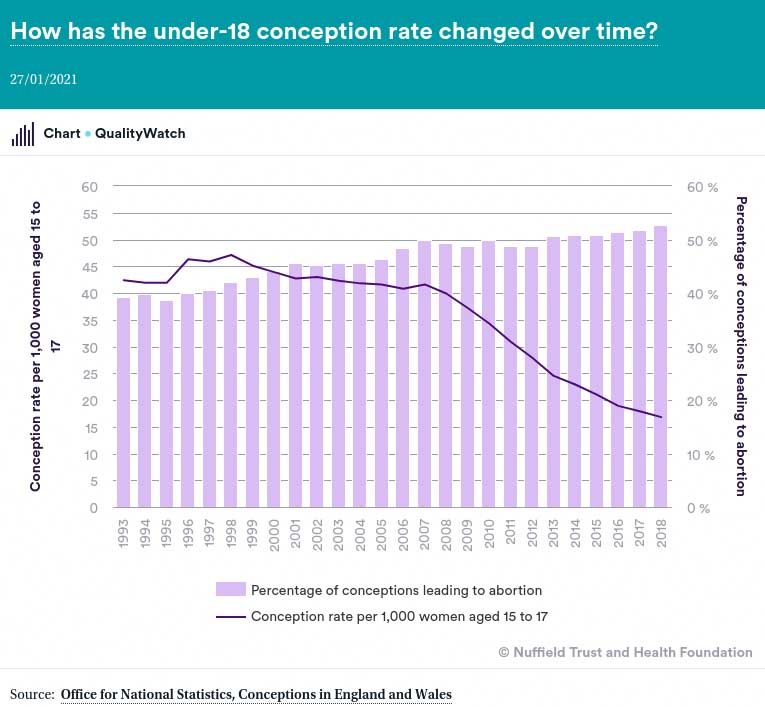

I don’t think it’s just the lockdown to blame: I think it’s a longer-term trend. Just look at the statistics for teenage pregnancies. How to explain the sudden and sustained drop over the past 15 years? The Office for National Statistics credits the launch of a Teenage Pregnancy Strategy for England, but I’m more persuaded by the argument that the arrival of smartphones has led to profound behaviour change.

Participation inequality in education and training

In the early years of the web, usability expert Jakob Nielsen explored the concept of participation inequality in online communities. He formulated the 1-9-90 rule to explain that in any online community of 100 people, one would be an active content creator, nine would be occasional contributors, and ninety would be passive lurkers.

Since then, social media and smartphones have arrived to give the impression of much more active participation and engagement. Yet have the fundamentals changed? My year of online teaching suggests a familiar pattern of participation inequality. It’s easy to turn up, but are people tuning in?

So much for a class of first year students. What of our experiences of online events in the past year?

Many doors have opened. I’ve suffered from Bled-envy in many past summers (this is many public relations academics’ favoured academic conference) and was able to join the opening sessions last year thanks to Facebook – at no cost, and saving the time and expense of travelling to rural Slovenia.

Whether free or paid-for, there’s the same participation-engagement equation as I’ve noted with my first year students. It’s easy to sign up for online events, but it’s much less easy to make the time to be an active participant.

In my experience, it’s a mistake for event organisers to assume that willingness to attend a two-day event in person translates to willingness to join the same event running over two days online. They are not equivalent. For one thing, the breaks at a real conference are often where the greatest value and enjoyment is gained (we’re social animals, remember). Yet breaks in an online conference that expect yet more online engagement are not breaks at all. Whose heart doesn’t sink at the mere mention of a breakout room?

One innovative response to this participation-engagement challenge was a conference that ran all week and was free to attend live, but made recordings available only to those who’d paid the conference fee. (This is similar to the MOOC model of higher education that makes the lessons free, but charges for assessment).

Other events have rethought the schedule and compressed the time to suit people’s online attention spans.

PR Academy’s Mind the PR Gap event in summer 2020 was turned from a one day face to face conference into two 90 minute sessions over two days.

Stephen Waddington’s free-to-attend #WaddsCon goes further and compresses four speakers into its one-hour lunchtime slot. Each is given just five minutes and a maximum of three presentation slides, followed by ten minutes for questions, thus rebalancing the participation-engagement equation. The first event had a speed-dating energy to it and brought together students, practitioners and educators. The second takes place tomorrow.

But there is still space for long-form, paid-for events. I’m looking forward to the PRCA International Summit next week that is scheduled in two half-day blocks over two days in much more traditional speaker and panel format.

Value can be delivered in traditional event formats, but what level of participation will be expected from delegates, I wonder?

At least it’s never been easier and cheaper to attend events: we maintain a busy PR Calendar here.