Briefing: public relations membership bodies

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

I’ve seen a couple of posts on LinkedIn asking for advice on whether to (re)join the CIPR or the PRCA. It’s not an easy question to answer without knowing the individuals. But it’s also becoming harder to distinguish between the roles of these two UK-based public relations membership bodies.

It was once easy. But since the PRCA started offering membership to in-house teams (in 2009) and to individual members (in 2011) there’s now considerable overlap. So how to make sense of the choice? And should you also consider joining other specialist or international associations since it’s not a simple binary choice between these two?

For part one of this briefing paper, focusing on CIPR and PRCA, I’ve sought a range of opinions on social media and through private conversations.

There are more contentious topics of conversation (Brexit comes to mind), but I find that people have fixed and firm views on their chosen associations. Many object to any discussion that the two bodies might even come back together to better serve the wider profession.

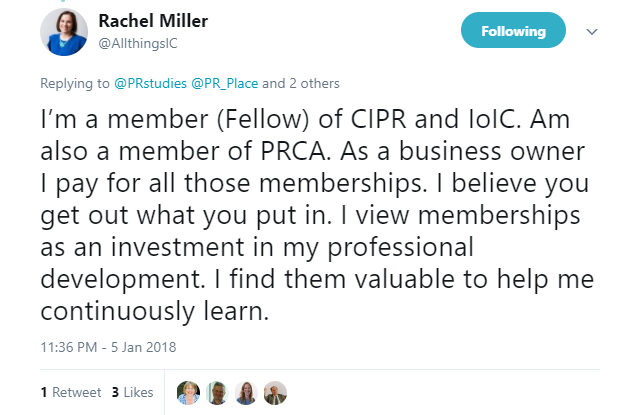

Rachel Miller probably tweeted the definitive answer to my open question about individual preferences.

Both the CIPR and the PRCA can provide value to active members (those willing to put in as well as taking out). Membership is an investment in professionalism, and for business owners and sole traders, membership of both is tax deductible (be sure to tell your accountant).

But Rachel Miller, as an internal communication specialist, is also a member of IoIC – the Institute of Internal Communication.

So if there’s no one primary professional body that we’re obliged to join, why should the choice stop with two? There are bodies representing specialisms (like IoIC) and there are others representing international practitioners (IPRA, IABC, Global Alliance, ICCO) – the subject of my next briefing.

For the record, I’ve been a member of the IPR (now CIPR) since 1998 – and was made a Fellow in 2013. I joined the PRCA as an individual member in 2011, having much earlier in my career been involved in the PRCA through previous employers.

I pay £225 a year to the CIPR and £120 a year to the PRCA (£100 plus VAT). There are additional costs to attending conferences, events and training through either body, though members receive discounted rates.

Rather than focusing on the costs, Rachel Miller’s tweet reminds us to view membership as an investment – in ourselves, in our profession, and possibly also in colleagues facing financial difficulty.

We are where we are

This year marks the 70th anniversary of what’s now known as the Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR). The Institute was established in London in 1948, the same year as the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA); it gained its Royal Charter in 2005.

The founding fathers were typically drawn from government comms roles – and the timing was no coincidence. Many of them had been involved in wartime comms and were looking to turn their backs on propaganda and establish a credible professional association suitable for an age of peace. From that day onwards, membership has been open to individuals (rather than to teams or organisations) and the emphasis has been on leading the industry towards professional status through qualifications and continuous professional development (CPD).

This historic emphasis on in-house and public sector comms led to the formation of breakaway body designed to serve the interests of commercial consultancies. In 1969, the PRCA (then known as the Public Relations Consultants Association) was formed to represent and regulate consultancies, a sector which was to experience remarkable growth.

For decades, the division remained clear. The (C)IPR was a professional body for individual members and the PRCA was a trade association for the larger consultancies. There was limited overlap and no individuals felt obliged to pay two membership fees.

Then it became personal.

Francis Ingham leads the PRCA, having previously been number two among the salaried staff at the CIPR.

Under his leadership, the PRCA has increased its numbers (it claims 400 consultancy members – and has expanded to include 500 in-house teams and many individual members). By adding up the numbers employed at these consultancies and within these teams, Ingham claims to regulate more members than any other public relations association in Europe (and that, in case you missed it, includes the CIPR – which counters with the claim to be ‘by far the biggest member organisation for PR practitioners outside of North America’).

To recognise this shift from being a trade association for the larger consultancies, in 2016 the PRCA changed its name while retaining its letters. These now stand for Public Relations and Communications Association and it now describes itself as a ‘membership body’ (while the CIPR describes itself as a ‘membership organisation’). Confused?

CIPR and PRCA both offer training and qualifications; both have codes of conduct. Both compete to be the voice of the industry and claim to regulate practitioners.

So it was a good day for Francis Ingham when the PRCA ruled that one of its member consultancies, Bell Pottinger, had breached the code of conduct in South Africa. Bell Pottinger was expelled from the PRCA last year and the news headlines precipitated the loss clients and the collapse of the business. The CIPR had no say in this since it regulates individuals, not companies.

But neither the CIPR nor the PRCA had much to say when Max Clifford died last year, since he’d avoided membership of either body (and wouldn’t have been made welcome, certainly not at the CIPR, for his honesty about not telling the truth).

And this brings me to the weakness of current arrangements. No one is required to join either body in order to work in public relations, and it’s hardly in the interests of bodies that gain their income from membership fees to exclude many from membership or make the entry criteria too exacting.

There’s no threat of sanction such as faces rogue medical practitioners who can be ‘struck off’ the medical register.

Even the most optimistic calculations leave most public relations practitioners outside the limited regulation of either body. The CIPR has a membership of around 10,000 individuals. If we accept Francis Ingham’s claim to regulate more than this, then we could assume a joint membership of up to 25,000, though this will be an inflated figure and it ignores those like me who are counted twice.

So let’s cautiously estimate at 20,000 those who are members of one or the other body. If 60,000 is a low estimate for the total number of public relations practitioners in the UK (not everyone doing PR-like work identifies it as public relations), then only about one in three practitioners opts into one or other professional body.

Since you don’t have to join any of these associations, Rachel Miller’s commitment to multiple memberships is all the more impressive.

So it’s not a binary choice between joining the CIPR or the PRCA. You are also free to find a more suitable group for your interests – or even to establish one if it doesn’t exist and if you believe there would be a demand from others.

Two approaches

There are two views on the current state of play in UK public relations.

There’s the free market view supportive of choice and competition. This ensures that all membership bodies continually strive to serve their members, and are forced to set their fees and prices for events at competitive rates. If they lose sight of our interests, we can punish them by cancelling our membership.

Some argue that this therefore is a golden age for practitioners. Take advantage of it while you can!

This same argument welcomes specialist groups serving the interests of specialists in analyst relations or investor relations, say. Again, many welcome the choice. But the logic of this argument is to splinter the broad church of public relations into many fragmentary groups with no common interest. Many of these would argue to ditch the term public relations for communication(s).

Those in science communication, to cite one example, are reluctant to acknowledge their links to public relations. And aren’t actors, speech therapists, telecoms engineers and many others paid for their skills in communications? Where does this leave public relations as a potential profession worthy of promotion, regulation and – no doubt, grudging – respect?

Then there’s the closed shop approach adopted by trades unions. If the workers’ voice is to be listened to by management, then they need to speak with one voice, through one set of representatives, backed by a credible threat of industrial action. Free choice of different unions would dilute the strength of this voice and management could get its way through divide and rule tactics.

Is this relevant to public relations? We know more about the power of network effects since the rise of technology and the internet. In short, networks increase in value as the group size increases (a phone network of one would have no value).

One strong, assertive membership body representing the majority of practitioners would have the power to increase standards through a mix of incentives and sanctions. Once the tipping point of majority membership had been reached, the minority would look increasingly exposed and amateurish, and employers might begin to doubt their seriousness and credibility and make hiring and promotion decisions accordingly.

The case for reunification

Since the reasons for the PRCA to have split from the then IPR no longer apply; since the interests of both bodies overlap; since the person now running the PRCA was once a senior manager at the CIPR – there does seem some logic to proposing a merger. I understand some such offer exists on the table.

The CIPR would probably keep its name (since the Royal Charter applies to this organisation), and because it has the longer history. But Francis Ingham would be in a strong position to negotiate either the top executive role or a big pay off.

Yet I also understand that there’s too much mistrust and ill feeling for this to be widely welcomed. Some feel the opportunity has been missed and the split may continue indefinitely.

Short of a breakthrough led from the top, then the only prospect for change would come from members ourselves. Yet many seem happy with the present arrangements and are willing to pay out for multiple memberships and to live with the contradictions. (Living comfortably with paradox: that probably describes daily reality for all public relations practitioners).

The case for the status quo

One of the problems both organisations face is reaching out to their members beyond London. Both bodies have regional and sectoral groups, usually run by volunteers, and these are often the main point of contact between the members and the national body. If your specialism is not currently offered, and you are willing to put yourself forward as a volunteer, you will probably find the support from the centre to set up your own group.

So, in summary, a membership body draws strength from its members. It’s about us, not them.

At the centre, the premises and salaried staff mostly perform an administration function – and there’s a tension between paying for a prestigious building and serving all members. This has been most evident at the CIPR which is proposing to change headquarters location once again to save money.

The public face of the CIPR is the practitioner chosen to act as president each year (sometimes through contested elections). Last year’s president, Jason MacKenzie, injected much energy into the drive for membership and professionalism and he’s been succeeded this year by Sarah Hall, whose vision for a #FuturePRoof public relations is of a more elevated advisory practice.

In this, and in some other matters, she has a shared agenda with the PRCA’s Francis Ingham.

Greater cooperation on topics of shared interest: it’s a promising development, if some way short of achieving a single voice for the profession.