Briefing: The misinformation age

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

Summary

Human behaviour is hardwired and slow to change; for evolutionary reasons, we are seekers after gossip and information. Advances in technology mean that what was once just idle gossip can now lead to the rapid spread of misinformation leading to disinformation and propaganda. Studies have shown that falsehoods spread six times as fast as the truth. The public relations playbook needs updating for this algorithmic, post-mass media age.

Introduction

The movie Wag the Dog was released in the UK in 1998. It tells of an attempt to bury a White House sex scandal days before a presidential election. A ‘spin doctor’ played by Robert De Niro is brought in to distract attention from this scandal. Working with Dustin Hoffman’s Hollywood producer they fabricate the appearance of a war in a faraway country few will have heard of (Albania, apparently a base for Islamist terrorists), complete with a returning American war hero and a catchy song. The trouble is, ‘you can’t tell anyone about this…’ The dark satire was about to take an even darker turn.

It’s funny. It’s shocking. It’s one of the stronger, though negative, portrayals of public relations on film. Yet it’s fiction; it didn’t happen. So there’s nothing to see here.

Except that fiction can reveal truths. Note the date this film was released. We’d had a White House sex scandal in the 1990s; we were soon to have an overseas war on a ‘false prospectus’. We had the mysterious death of an expert weapons inspector. We were soon to become all too aware of Islamist terrorism. And photographic evidence is becoming less and less convincing given the ability to manipulate images pixel by pixel and create deepfake images and video using AI.

The imaginary world of Wag the Dog is not so far from our reality.

Fiction directs us to the difficult questions through entertainment. What is fact? What is fiction? And what is the role of public relations: master manipulator or truth teller?

The information age reaches high tide

11 September 2001, the most notorious date this century (widely known as 9/11 following the US date-day order, and suggesting the emergency dial code 911).

I’d heard the shocking news of a jet crashing into the World Trade Center building and like so many others turned on 24 hour rolling TV news in time to see the second tower struck.

In retrospect, was this the high water mark for the information age? Newspapers still commanded large circulations. The BBC was a largely respected broadcaster in the UK and internationally though it had competition. At a time when the news was so attention-grabbing and disturbing, who else to trust but our national broadcaster?

The information about the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington preceded any disinformation or inevitable conspiracy theories.

The internet was more limited than it is today but it was good for one thing: providing us with information. This was exemplified by the great enduring achievement of the web’s first decade: Wikipedia. That a not-for-profit community run by volunteers was capable of building and verifying so much information is commendable and improbable. Yes, it contains errors. Yes, it can be vandalised. But it’s a self-healing system. It serves no commercial interest.

Yet Wikipedia is problematic for public relations practitioners since we’re not deemed worthy to create or edit an entry on the grounds that we do not meet the test of having a ‘neutral point of view’. In other words, we can’t be objective reporters of the truth since we’re paid advocates for one point of view.

This is precisely the distinction made by journalists, who will sometimes make the case that only they can tell the whole truth about a story, while we can only see one perspective on it.

So I may be painting a picture of an overly-idealised world that had respect for the truth and objective fact but I’m acknowledging that public relations was a peripheral player in this information ecosystem.

That was a quarter of a century ago. Was there something prescient in Robert de Niro’s spin doctor in Wag the Dog? Could public relations be such a dark art? Could it manipulate reality?

We’re about to enter a world of ‘alternative facts’, a world Gareth Thompson calls Post-Truth Public Relations.

What is true?

One of the techniques used by those spreading misinformation and disinformation is to create such noise around a topic that we begin to doubt the truth. It was used for decades by the tobacco industry; it’s been used in more recent decades by those seeking to challenge the consensus among climate scientists.

Yet is it even helpful to seek an overly simplistic contrast between true and false because those seeking to manipulate perceptions (and these are often public relations practitioners, remember) will base their arguments on a kernel of truth. So rather than attempting to demolish arguments fact by fact, like a lawyer in court, it’s more useful to discern the communicative intent.

Who is behind this information? Are they a reliable source? What are they seeking to achieve by communicating this information?

Misinformation, disinformation and public relations

Before moving on with this argument, let’s be clear on one thing. I’m not dreaming up some long lost golden age in order to draw a contrast with the present day.

Public relations has always been manipulative (its aim is usually to manipulate, or change, people’s awareness, attitudes or behaviour). It has its origins in propaganda.

Take two examples relating to one industry. Edward Bernays is praised as a master of social psychology and the story is still told of his ‘torches of freedom’ publicity stunt which was part of a campaign to double the market for cigarettes by making it socially acceptable for women to smoke. So smoking was presented by Bernays as advancing the cause of ‘women’s lib’.

This was decades before the medical evidence came clear on the connection between smoking and ill health (gathered in a report from the Royal College of Physicians published in 1962).

Yet the tobacco industry had jobs and profits to protect and for decades tried every trick in the public relations playbook to obstruct the truth, to obscure the science, and to delay the inevitable.

Long before widespread talk of misinformation and disinformation, we were aware of the uses of fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) to obscure the truth.

To this day, there’s a team of activist-researchers at the Tobacco Control Research Group at University of Bath ‘exposing tobacco industry influence on health policies around the world to reduce smoking and save lives’.

Public relations being used to obscure the truth: it’s on the record. Meanwhile the truth itself has become contested ground, seemingly incapable of objective verification.

The (simple) psychology of persuasion

When did you last change your mind on a matter or any importance? There’s much talk at election time about marginal constituencies and swing voters, but that’s because it’s so hard to get people to change their mind. Many people have long-established party affiliations and there’s another large group convinced that ‘all politicians are the same’ and that there’s no point voting for any of them. Others would rather simply stay at home than cast a vote for ‘the other side’.

I’ll give you an answer to my question. The fact that I can remember the moment when I changed my mind shows these to be exceptional. It was a female undergraduate asking in class why those sectors that men have traditionally found interesting (let’s say business, politics and sport) are deemed more important than sectors more commonly associated with women’s interests (let’s say fashion, beauty and celebrity). Ouch. I’d been found guilty of unconscious bias and should strive to be better.

It’s a privilege of being a university lecturer that I not only have the opportunity to shape how others see the world, but I open myself to different worldviews and life experiences. Yet how many of us are regularly exposed to people of different ages, different backgrounds, different worldviews?

Don’t we seek out people like us? Don’t we take comfort in a close circle of family and friends? Isn’t it fun to cheer ‘our’ team, to join that march with many other likeminded people, to sign that petition. We’re tribal animals with herd instincts, remember.

It’s hard for us to change our minds because it’s expensive for us to do so. Humans have evolved large brains that absorb considerable resources and in evolutionary terms the time and resources spent thinking through a problem could cost us our lives. Much easier to follow our instincts, or simply follow the crowd.

This is what’s meant by ‘thinking fast and slow’ in Daniel Kahneman’s phrase. Fast thinking is instinctive; slow thinking is rational and deliberative.

It lies behind behavioural economics (sometimes known as ‘nudge theory’). Since it’s often too big a leap for people to make a considered, reasoned decision, even if in their own best interest, then what are the triggers that can nudge them towards different behaviour?

So following the earlier example, a rational health warning – even one as stark as Smoking Kills – will be ineffective in the case of the addicted and habitual smoker. Yet increasing the tax on cigarettes can act as a punitive nudge to behaviour change. Or the warnings over passive smoking send a signal that while it may be within the law for you to damage your own health by smoking, it’s not socially acceptable for you to harm those around you. If those close to you then choose to apply some pressure over your smoking habit, then all the better.

Misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories

This may feel like a long detour through recent history and through human psychology to reach the point of this briefing: a discussion of misinformation and disinformation.

But it’s important to establish the long view so we can place the last two decades in context. Technology progresses fast but human evolution is slow.

There have always been conspiracy theories; they’re effective because they appear to explain otherwise confusing events. They save us from having to think the hard and slow way and also reassure us by telling us that we’re privy to insider knowledge that others want to suppress. They place us in the in-crowd.

What’s new is the way conspiracy theories can emerge as fast and with apparent equivalence with reported fact via social media channels. What’s new is the ability of technology to create the full multimedia experience, as with the fake war in Wag the Dog.

There’s an important distinction, and a memorable way to recall it. Misinformation is spread mistakenly. Disinformation is deliberate.

‘When disinformation is deployed in the service of a political agenda, state-sanctioned or otherwise, we call it propaganda’ writes Sander van der Linden, the Cambridge academic and author of Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity. ‘Disinformation and propaganda are the more dangerous subsets of what everyone generally refers to as ‘fake news’.’

Public relations can be guilty of misinformation and of disinformation, yet is simultaneously in the first line of defence against both.

First, the case for the prosecution. The outputs of public relations are ‘on the record’ complete in many cases with a digital audit trail. So any factual errors can be copied and shared (and traced back to source). This gives us an obligation to check and double check any names, facts and figures we’re sharing. But it’s not so simple, as facts can be contested and interpreted in different ways. A multi-million pound bonus paid to a chief executive may or may not be excessive; but it may well be a figure we choose to leave out of a results announcement, preferring to focus on increased profits, say. Is the omission of this figure likely to lead to misinformation? What obligations do we have beyond accuracy to provide as full a picture as possible?

Then there’s the charge that public relations can be used to spread disinformation. Examples of this are elusive in commercial public relations and I still cite the pre-Wag the Dog example of the eyewitness testimony by ‘Nayirah’ presented to US Congress following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait that preceded the first Gulf War. Hill & Knowlton was subsequently condemned for disguising the affiliation of the key witness (she was a member of the Kuwaiti ruling family) and preparing her emotional testimony (she’d apparently witnessed Iraqi soldiers throwing babies out of incubators in a maternity ward). Certainly, Hill & Knowlton received a handsome fee from Kuwait’s rulers for its efforts.

Then there’s the knowing fictional example of disinformation from Robert de Niro’s spin doctor character in Wag the Dog. ‘There is no B3 bomber – and I don’t know why these rumors get started!’

Examples of disinformation are much easier to cite from political campaigns, where it’s normal practice to attack your opponents below the belt. Was the Vote Leave message that remaining in the European Union risked millions of migrants arriving from Turkey an example of disinformation? Turkey’s application for membership of the European Union was on hold and the most optimistic timetable would put its accession decades into the future. So it was certainly an exaggeration and arguably deliberate spreading of an inaccurate rumour. Yet campaigners are unapologetic: they say it’s an example of what could happen given the free movement of people within the European Union. And besides, they won the vote!

So public relations has the ability and motive to spread misinformation and disinformation, hence the increased emphasis on standards of ethics and professionalism in the age of digital and social media and generative AI. Public relations, like propaganda, is a powerful tool that can be used for good – or for the other side.

Polarisation

I still chuckle over a piece of dialogue from the Just William stories. ‘Opposite of cat? Dog’. In a child’s worldview, this question is easily answered with no thought needed.

Yet why should a cat have an opposite? What is the nature of this opposition? What about the evidence of our own eyes that cats and dogs can coexist happily in the same household? The adult mind can make things much more complicated.

Everywhere we look, binary choices present an easy way to simplify the world: Democrat or Republican. Capitalism or Communism. Unions or management. Coke or Pepsi. Liverpool or Everton. Tea or coffee.

They’re hardwired into some electoral systems such as the first past the post elections for the UK parliament. Multiple parties and even independent candidates can stand in any one constituency, but at a national level the choice is binary: Labour or Conservative.

Binary choices simplify a confusing world; there’s a drama to the choice (heaven or hell). Such contrasts make it easy to win the argument (because who would choose the latter, given this choice?).

Yet such easy choices can be countered by alternative binary choices. A woman’s right to choose appears to be a winning argument in that who outside the Taliban would argue against this right? So the counter-argument is presented as an unborn child’s right to life (again, who could argue against that?). There are now two tribes, both fervently believing they’re right.

Then, in the algorithmic way (if you like this, we think you’ll like that) people in one camp are more easily converted into different coalitions. Welcome to the culture wars.

How to debunk conspiracy theories

Having discussed flat earthers and the reptilian conspiracy theory, Sander van der Linden argues ‘all conspiracy theories have something in common: they are characterized by persistent beliefs about secret and powerful forces which are operating behind the scenes to implement some sinister agenda…. They are a fascinating example of an evidence-resistant worldview.’

However irrational and inexplicable they may seem, ‘conspiracy theories offer simple causal explanations for what otherwise seem to be chaotic and random events.’

This is the key point. Nor should conspiracy theories always be seen as malign: sometimes the fates conspire against us, as the saying goes. ‘Conspiracy theories establish a sense of agency and control over the narrative of world events.’

This becomes a public relations issue because in our roles we may seek to put the record straight on misinformation and disinformation. Yet a straight rebuttal of an argument could merely serve to reinforce it. Sander van der Linden explains this using the example of the conspiracy theory around the MMR vaccine being linked to autism. ‘The statement ‘vaccines do not cause autism’ may just strengthen the association people have between ‘vaccine’ and ‘autism’. A negative becomes a positive reinforcement.

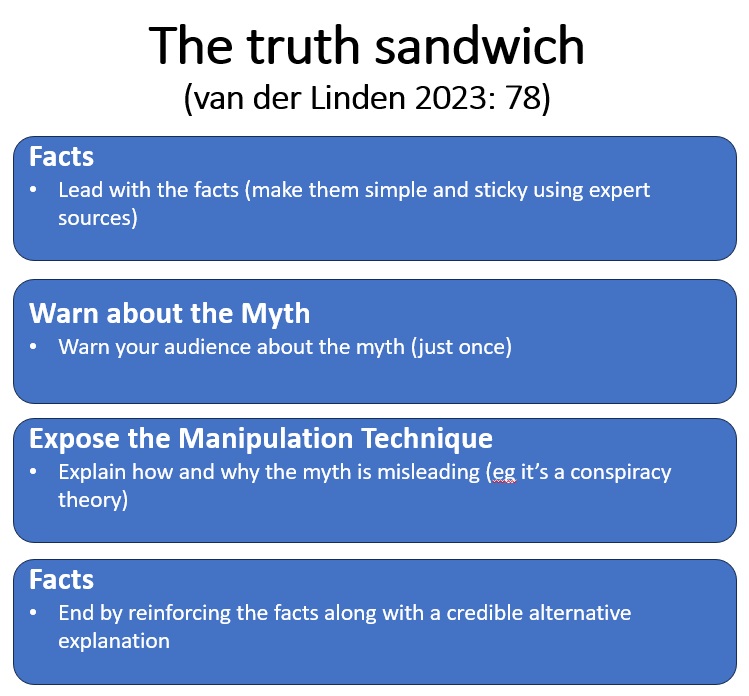

So how should you debunk a conspiracy theory? Van der Linden cites a model referred to as ‘the truth sandwich’. ‘The idea is to layer the falsehood with the truth, which should contain an alternative explanation for the myth. The ‘meat’ of the sandwich should consist of explaining why the myth is misleading (without repeating it).’

How misinformation spreads

It’s in human nature to gossip; in evolutionary terms , our survival has depended on us being well informed on matters that could affect our safety. But for most of human history, idle – or malicious – gossip has had a limited reach. Yet successive technology advances from the printing press to email, the internet and private messaging services have increased the speed and effectiveness by which messages spread. And in all these cases, the message is spread by a named or known, credible person.

We became familiar with the R (reproduction) number during the pandemic. This is a number an infected person could pass the virus on to. Just as viruses can spread through a population, so ideas – including fake news – are spread person to person. A couple of decades ago this process was seen as highly desirable: viral marketing was seen as a clever ploy in the early years of social media. Now, the rapid spreading of ideas on social media (and on encrypted private messaging services such as WhatsApp) is more often seen as a negative phenomenon.

Indeed, this negative influence was proven by an MIT study from 2018, looking at the spread of rumours on Twitter. The study found that falsehoods spread more widely than the truth.

‘The researchers calculated that, on average, it took the truth about six times as long as a falsehood to reach 1,500 people. In other words, lies had literally made their way halfway around the world before the truth had time to get its shoes on’ explains van der Linden. ‘In total, falsehoods were 70 per cent more likely to be retweeted than true claims.’

‘Fake stories are more infectious than true stories.’

Perhaps this is just another way of saying ‘the devil has all the best tunes.’ Vice is so much more interesting than virtue.

Nor can the public relations business credibly pose as guardians of the truth while continuing to use 1 April (April Fool’s Day) as a hook for spreading entertaining falsehoods for promotional ends. #sorrynotsorry

Neither can journalists claim to be gatekeepers of the truth when the commercial pressure to be first with the news, to deliver a striking headline, means that the entertaining headline has been a goal in itself (‘Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster’) regardless of the truth or the reliability of the source (in that case, Max Clifford). Nor do published corrections carry the prominence or the virality of the original fake news.

Echo chambers and filter bubbles

As Sander van der Linden explains it: ‘by entering an echo chamber people are able to selectively seek out information that reinforces their pre-existing views about the world, whilst avoiding exposure to counter-content that may question these beliefs in potentially uncomfortable ways.’

The concept of the filter bubble originated with Eli Pariser in a book of the same name. This is where social media algorithms give you more of what you like to the exclusion of other content or perspectives.

The same applied in the mass media age when readers of The Sun newspaper, say, would be buying into an editorial worldview. But in the UK broadcast TV news was held to greater standards of impartiality.

Yet in the age of streaming, someone spending their time binge watching Netflix is not exposed to any news at all (whether partial or impartial). My students tell me they receive their news from social media.

A distinction between filter bubbles and echo chambers is that the former is algorithmic and so can only exist online whereas the latter can exist offline. Most of us have a tendency to surround ourselves with ‘people like us’. We are instinctively tribal.

Why we love to hate

Researchers have shown that negative or divisive content achieves more engagement on Facebook and Twitter than positive content. You could say we love to hate.

Since most public relations content is necessarily positive, and since practitioners are under constant pressure to achieve results, then this pushes us towards ever more contentious and edgy content. This runs the risk of creating a backlash which may be great for engagement, but is potentially bad for reputation. It also raises ethical questions, which leads us to the Cambridge Analytica case.

The British political consulting firm had acquired Facebook data harvested via a fun personality quiz (and scraped from their friends’ profiles too) to develop models on how to micro-target voters with political messages based on their known likes and preferences. This was a service they could sell to political campaigns: big data enlisted in pursuit of election victory. It was eagerly taken up by far right interests, as documented by investigative journalist Carole Cadwalladr and by the subsequent investigations of the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

Yet is this another example of fake news? We want to believe that malign forces are attempting to influence elections. And it was in Cambridge Analytica’s commercial interest to talk up the potential persuasive power of its use of data. Subsequent researchers are not so convinced. Remember, it’s hard to get people to change their mind, so the best you can do is reinforce people’s existing preferences and prejudices. Powerful, but not necessarily a guaranteed election winner. As with most advertising, the persuasive power is surprisingly low.

And yet it might be enough in a close-fought election such as a US presidential election or the Brexit referendum in the UK.

Sander van der Linden’s verdict? ‘Although traditional campaigns may have struggled to persuade voters, social media can now help optimize the identification and micro-targeting of those individuals most open to persuasion via their digital footprints.’

Prebunking (inoculation theory)

The phrase ‘prevention is better than cure’ is well known in medicine. It also applies to misinformation and disinformation.

The aim is to build preemptive resilience (in other words, to inoculate the brain against falsehood).

Van der Linden argues: ‘the ideal application of psychological inoculation is purely prophylactic: before people have been exposed to the misinformation.’ But ‘therapeutic inoculation’ – after people have been infected by the misinformation – can be effective too.

‘Of course, there must come a point where the virus spreads so deeply that you are simply left with no option other than plain old debunking… Effective debunking requires that you provide a compelling alternative explanation.’

We need to heed the primacy effect: we tend to remember the first and the last thing we hear; so it’s always better to get your retaliation in first.

Six Degrees of Manipulation

Just as there are established principles behind persuasion and influence (Robert Cialdini identified six: reciprocity, commitment, social proof, authority, liking and scarcity), Sander van der Linden suggests Six Degrees of Manipulation based on the DEPICT acronym.

Discrediting: Those producing disinformation know they will face challenges from journalists, fact checkers and other sceptics. So they attack the source of the criticism to deflect attention away from the accusations (‘fake news’, ‘mainstream media’).

Emotion: Emotional content is more likely to gain traction; fear and hate are powerful motivators..

Polarisation: Polarisation involves the deliberate attempt to drive people apart, to move them away from the political centre.

Impersonation: Medical practitioners may be especially credible experts on questions about vaccines. But what’s to stop anyone with a doctorate in any discipline using their title to gain implied authority? Indeed, what’s to stop anyone claiming to be a doctor online?

Conspiracy: ‘An effective conspiracy theory leverages real events to cast doubt on mainstream and official explanations,’ writes van der Linden.

Trolling: Online trolling uses emotional content to provoke a response. They range from mere attention seekers to those using the technique to manipulate public perception. The difference between a troll and a bot is that the troll has a human touch.

The new public information playbook

Here’s a summary of some of the challenges we face along with some approaches to solving these challenges.

- Media literacy

In the mass media age (broadly, the twentieth century) there were limited and often government-controlled media channels available to the public. We needed to be aware of the dangers of state propaganda and to inform ourselves of the likely bias through private ownership of newspapers. But we shared the same few media channels and so had a common narrative to learn about and help us understand events.

We’re well past that stage. Someone watching Netflix is not exposed to any news; that same person probably receives news through social media. But because social media algorithms give us more of what we like, there is no longer a universal, shared experience. YourTube is not MyTube.

This fragmentation makes it easier for those seeking to polarise people and drive them into opposing tribes.

Therefore media literacy has never been more important. Some may dislike the BBC for its perceived bias; many may resent paying the licence fee; but all should understand the impartiality rules that apply to broadcasters in the UK. No such rules apply on social media. We should acknowledge the valuable work journalists perform weighing up various sources (including public relations sources) and fact checking their sources and stories.

The prebuttal and inoculation approaches recommended by Sander van der Linden involve educating and informing. His team of researchers have used games as a more entertaining way to educate people about the dangers of misinformation.

Since public relations practitioners work with and in the media, we are informed professionals who can all contribute to the challenge of educating people about misinformation in the age of social media algorithms and AI. We can do this through our own social media channels (see below for some recommended experts to follow), through the training we provide to new team members and by volunteering to talk in schools and universities.

- Fact checking

While artificial intelligence can add to the problem through massive misinformation campaigns supported by bots, generative AI and deepfake audio and video, the truth will always be chasing after the falsehood.

Yet AI tools can also aid the process of fact checking by matching the power of AI to generate false narratives with real time fact checking.

Fact checking has long been an important adjunct to quality journalism; it now needs to be enlisted for the purposes of quality, ethical public relations.

- Prebunking and inoculation versus rebuttal and debunking

If someone shares a falsehood about you, your organisation or your client in public, then the automatic instinct is to correct the falsehood fast. Yet in the age of social media this may not be wise. Official messages rebutting a rumour or falsehood can merely serve to magnify the harmful message. ‘Vaccinations do not cause autism’ merely restates the supposed link between vaccines and autism. It adds more results to keyword searches for these terms, thus appearing to endorse the original conspiracy theory.

A better approach is to inoculate people against misinformation. Just as prevention is better than cure in medicine, then prebunking is better than debunking in public relations. Sander van der Linden uses this inoculation metaphor throughout his book.

‘Just as exposing people to a severely weakened (or dead) strain of a virus triggers the production of antibodies to help the body fight off future infection, the same can be achieved with information.’

- Social media

Stay away from social media as the best defence against misinformation suggests Sander van der Linden. ‘About 50% of the population get their news from social media, which is problematic.’

Perhaps this isn’t as hard as it sounds. Many of us have chosen to stay away from X (formerly Twitter) and many more are using it less, and are becoming more mistrustful of what they find there.

And yet as people use ‘traditional social media’ less, they’re relying more on ‘dark social’ channels such as WhatsApp which is more problematic for public relations, as these messages are shared in private rather than in public.

- Ethics

Given its roots in propaganda and its role defending the indefensible, it’s hard for public relations practitioners to pose as ‘good cop’ when it comes to questions of truth and reliability. That’s why ethical practice is more important than ever: we are under suspicion so need to be demonstrably transparent and reliable. Are we checking and double checking the facts we share in the public domain? Are we taking steps to avoid exaggeration? Are we omitting any significant information? Are we sufficiently robust in challenging our bosses and clients? Are we disclosing that public relations is the source (and thus avoiding discredited techniques such as ‘astroturfing’). Are we disclosing our own use of AI?

- Resilience

Consultancy Kekst CNC, part of Publicis Groupe, has been tracking misinformation used against FTSE 100 companies and advises companies to build resilience against information attacks (just as they have had to build resilience against cyberattacks) in the following three ways:

- ‘Identify vulnerabilities to disinformation, with a frank audit of how you might be exposed and who is likely to target you with disinformation, and how. Monitor mainstream media, non-credible outlets, social media, and influential voices for emerging themes and campaigns.

- ‘Be prepared for disinformation campaigns when (not if) they come. Have a plan, including how to assess the motivation of disinformation, counter it without amplifying it, reduce its ability to propagate, mobilise third-party voices, and work with partners. Put in place clear guidance for handling potential scenarios.

- ‘Build resilience in high-priority audiences that are most vulnerable to disinformation. Pre-empt possible campaigns by explaining in advance their motivation, so audiences expect and discount them. Project trust-worthiness: Pre-bunk; Reliably Inform; Offer balance; Verify quality; and Explain uncertainty (PROVE).’

Sources and further reading

Books

- Alison Goldsworthy, Laura Osborne, Alexandra Chesterfield (2021) Poles Apart: Why People Turn Against Each Other, and How to Bring Them Together, Random House Business

- Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway (2011) Merchants of Doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming, Bloomsbury

- Thomas Rid (2021) Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare, Profile Books

- Philip M. Taylor (2003 ) Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Era (third edition) Manchester University Press

- Gareth Thompson (2020) Post-Truth Public Relations: Communication in an Era of Digital Disinformation, Routledge

- Sander van der Linden (2023) Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity, Fourth Estate

Website

- https://inoculation.science/ Resources for educators

Reports

- Kekst CNC: FTSE 100 State of Disinformation Report, H1 2023 (PDF available on request from Michael White, see below)

- Sarah Cook, Angeli Datt, Ellie Young, and BC Han (2022) Beijing’s Global Media Influence: Authoritarian Expansion and the Power of Democratic Resilience, Freedom House

Podcast

- The PRmoment Podcast: Alex Aiken on how the UK government attempts to counter the disinformation campaigns of Russia and China (1 November 2023)

Organisations and individuals to follow

- Alex Aiken, GCS

- Nick Barron, MHP Group

- Global Disinformation Index (not for profit organisation)

- Alison Goldsworthy

- Shayoni Lynn, Lynn Global

- Holly Mercer, Logically

- Chris Morris, Full Fact

- Stefan Rollnick

- Michael White, Kekst CNC