Educator, teach yourself!

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

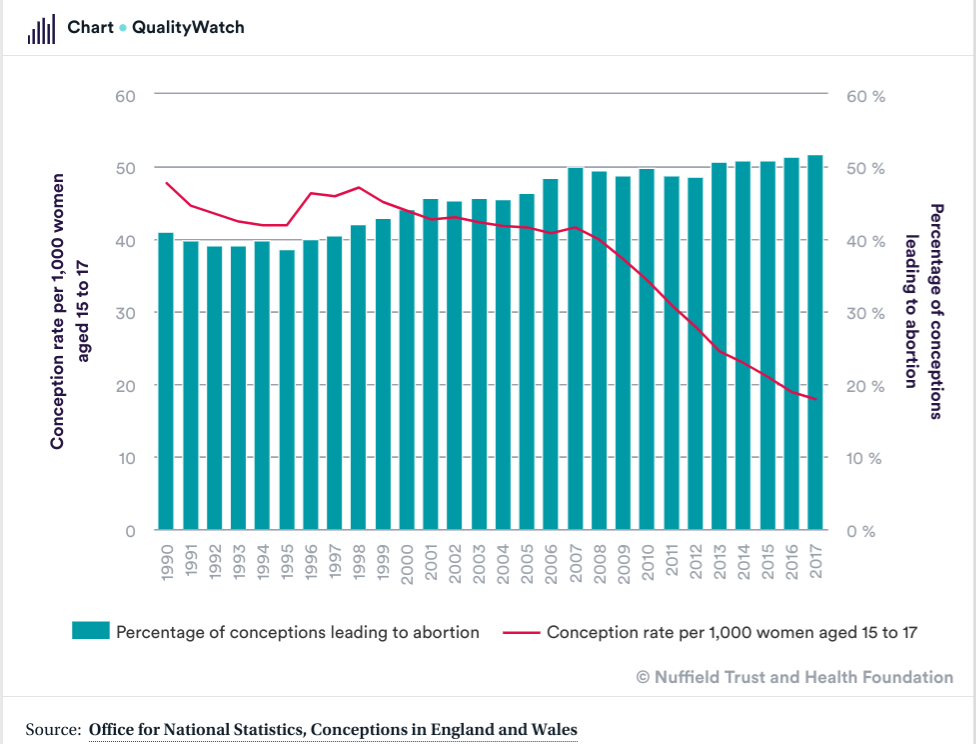

The UK teenage pregnancy rate had for a long time been persistently high, at between 40 and 50 pregnancies per thousand females aged 15-17. Then something changed. From 2007 the rate started dropping and has continued to do so ever since, so that by 2017 it was under 20. Just look at the line in red.

What could explain this sudden and sustained behaviour change? Was it the wider availability of contraception? Was it thanks to a new public health message? Was it to any change in sex education in schools? How I’d love to credit an effective communication campaign.

What could explain this sudden and sustained behaviour change? Was it the wider availability of contraception? Was it thanks to a new public health message? Was it to any change in sex education in schools? How I’d love to credit an effective communication campaign.

No. The most credible anwer I’ve seen comes from a consumer technology development. 2007 was the year Apple introduced its iPhone. The fall in unplanned teenage pregnancies is in inverse proportion to the adoption of smartphones. How so?

Picture the scene in households up and down the country. Teenagers being criticised for wasting time anti-socially in their bedrooms, messaging their friends. What did parents want? For their teenage sons and daughters to be outside getting drunk and risking getting pregnant or contracting sexually transmitted infections?

Two lessons emerge from this anecdote. The first is that technology adoption is often driven by young people. A generation earlier Vodafone executives had decided to bundle 160 character text messaging for free into their new mobile phone services, because they could not see this service being of much use to business people using the numeric keypads common at the time. Guess what happened next?

The second lesson is that there are unintended consequences of technology – and they’re not all bad.

Now back to our present predicament.

I started teaching ‘Digital Communication Management’ to a class of postgraduate students in January. The class is still running, though it’s had to switch to online delivery. The course is of my devising, but it covers much of the same ground as the recently-introduced CIPR Digital Communication Diploma.

Class members come from four continents (the Americas, Europe, Africa and Asia). Some returned home while they could; others remain in isolation, in some cases far from home. It’s unlikely we’ll meet again which is a loss because the university experience is about so much more than a series of lectures, classes and assignments.

But as a learning experience, the timing could not have been better. Many people across the world are suddenly confined to home and unable to go to work or to their normal meeting places.

Some have resorted to traditional pass-times: board games, learning musical instruments, reading those unread books. But most have turned to digital and social media to replace face to face interaction, just as a decade ago texting began to replace sex.

We’re living through a live experiment in sudden technology adoption. When did you last take out cash from an ATM? When did you last use notes and coins? Thinking ahead, will there be a dash back to cash or will we have learnt to do without?

Not all work can be readily done from home, nor can all work be digitised. There will be pent up demand for plumbers, builders and car mechanics when we’re allowed to return to near-normality. But much more can be done remotely than would have been possible before smartphones and reliable internet connectivity, as discussed by the BBC’s technology correspondent Rory Cellan-Jones.

There will be losers. Airlines may not only have a short-term cashflow problem, and what of train operators?

I’ve found it harder to switch to online delivery than I should have, given the subject I’m teaching.

Ann Pilkington, Heather Yaxley and Chris Tucker have already shared their much lengthier experience of running online classes, and I’ve learnt some lessons from them. But I’m still finding the nuts and bolts hard.

Why, when Netflix can stream feature films and TV series as you watch them, are PowerPoint slides with a video and audio track added such monstrously large files, even when compressed? Why does it take so long to upload them to the VLE, and why do they have to be downloaded before they can be watched or listened to? I’ll have to give Panopto another go; it’s been designed for just this purpose.

What else have I learnt?

I’ve learnt that while adults and teachers are turning to Zoom or Skype or Google (Hangouts) Meet, the teens have turned to Houseparty. Me neither until last week.

While Instagram has struggled to find a purpose during #stayathome (all those aspirational travel pictures are either not possible or are now socially unacceptable), TikTok is having a really good lockdown.

It’s a stream of 15 second videos featuring dance moves set to music that readily become memes. You’ve not tried the Oh Na Na challenge yet? Or watched people apparently levitating upstairs attempting a #stairshuffle?

But there are educational moments too: I learnt from a nurse how to remove surgical gloves.

TikTok suits our times. It’s small scale, suitable for home, and it provides endless feelgood moments alongside the remorselessly worrying news.

It’s good too to recall a time when the terms infectious and contagious were seen as positive concepts. It’s a reminder that we’re a social species, and we’re also creative.

These are my two highlights from media interviews with academics in the past week. Robin Dunbar from Oxford – whose ‘Dunbar number’ describes the limits of social connections our primate brains were evolved to manage – was discussing another primate behaviour: our need for touch, now so much curtailed during the lockdown. And Sapiens author Yuval Noah Harari talking from Jerusalem, was explaining that universities had spent twenty years talking about online learning and doing little, but then managed to switch all courses online with just one week’s notice.

Progress is sometimes indiscernible; at other times it’s sudden and dramatic.

I mean to remind my class there’s never been a better time to hangout on social media – and call it work. Never has studying Digital Communication Management seemed more timely.

Tick tock, tick tock. How are you spending your lockdown?