Mind the Truth and Lies Gap

Summary of day one of Mind the PR Gap 2022

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

What’s the difference between a bullshit artist and a liar?

The liar cares about the truth – their aim is to stop others from learning it.

Whereas the bullshitter doesn’t care about the difference between truth and falsehood.

This insight, from Professor Marianna Fotaki of Warwick University, is an example of why we should listen to academics; they can give us new ways of looking at old problems.

The issue of fake news is not new; what’s changed is our mediatised society – the ability of everyone to make news and influence others.

What's behind the rise in post-truth politics? Who could she have in mind when she talks about 'bullshit artists' and dishonest leaders? #MindthePRGap

— PR Place Insights (@PR_Place) July 13, 2022

She talked of ‘narcissistic leadership’ that thrives in post-truth circumstances. Populist leaders create narratives to portray themselves as indispensable, the only ones who can resolve problems and defend us against potential enemies.

The ability to lie and get away with it creates social power.

She’d referred to examples from the US and UK, so it was easy to assume that the populists she had in mind included Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Yet her prime example of narcissistic leadership was former Nobel Peace Prize nominee Vladimir Putin. She argued that our press had turned a blind eye to Putin until he proved a direct threat to western Europe over gas supply and by invading Ukraine.

Are the media giving a special pass to certain individuals? Just three companies dominate 90% of the national press in the UK.

So much for the problem; what about the solution? She talked about values-driven leadership. Leaders are not invulnerable: they share the same planet and all our lives are limited. Leadership must involve more than attaining and staying in power.

If this analysis of nationalism and populism can be viewed as focusing on the political right, what about a left-wing perspective?

Our next speaker, Dr Carol Stephenson from Northumbria University, provided a case study from County Durham, classic Red Wall country. The themes of her case study were environmental activism, localism, and legitimacy.

For context, deep mining for coal ended in this area in 1980. The case study involved a campaign to prevent open cast mining near Consett on the grounds of environmental protection. Where the miners’ strike in the 1980s had been a unifying event for the left, by the 2010s coal had become demonised and the environment had risen up the agenda. So how to balance environmental protection with economic development? How to balance local with national and international interests?

She noted how she’d grown up with ‘carboniferous capitalism’, with miners and steelworkers in her family. The area had a long and proud history of trades unionism. She referred to the previous weekend’s Durham Miners’ Gala attended by 250,000 people celebrating coal and their shared past.

In terms of the collapse of the Red Wall, she mentioned that Laura Pidcock, the young Labour MP, ‘very left wing, very close to Corbyn’, had lost her North West Durham seat in 2019. ‘Unthinkable – but it happened.’ Some argued she’d lost local support for backing this environmental protection campaign. The association with coal in County Durham runs deep, and is associated with self-respect.

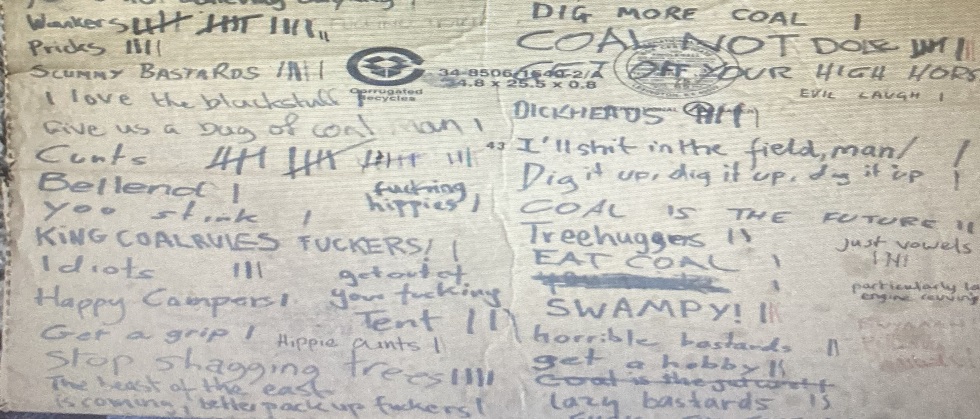

A key piece of research was the ‘insult board’, a record of what was shouted by those passing by the protest camp and by those on social media.

Here’s the insult board. ‘They look like fucking tramps’. Primeval fears are being drawn on. #MindthePRGap pic.twitter.com/EB2kR8z4KQ

— PR Place Insights (@PR_Place) July 13, 2022

In general, the protesters were characterised as outsiders (not local and so not legitimate) even though there were locals among them. The protesters were being ‘othered’ by the community. ‘Get a job!’ is probably the most important thing that was being shouted at the protesters, and is among the more polite insults recorded (‘stop shagging trees’, see image above).’ When we look online it gets even worse!’

‘If today is about Being Human, there’s very dehumanising language here. Primeval fears are being drawn on.’ She cites Imogen Tyler’s book Stigma that explores the demonisation of groups including asylum seekers and working class mums.

An important concept is the ‘generative’ nature of insults, especially online. I say something, and you add to it. This leads to an increasingly shrill echo chamber as people outbid each other in their righteous indignation.

She observes that this is not accidental; it’s a part of divide and control, of rule by division. Who or what is to blame? In her analysis, it’s austerity and neoliberalism rather than the media and social media that has pushed people to the political right rather than to the political left.

So, we’re in a post-truth age of divide-and-rule politics. We’re also entering a period where artificial intelligence will become more pervasive. What can we learn about algorithmic public relations? About human brains and computer algorithms? About the computational turn? Are humans in opposition to data and computers?

Dr Simon Collister, a consultant with a past life as an academic, provided a not-entirely-pessimistic overview.

He argued that algorithmic PR has the potential to improve the efficiency of day to day operations, but runs the risk of smoothing out nuance and reinforcing and amplifying problems. ‘The computational turn has forced things into a binary choice: either it’s wrong or it’s right. There’s no grey space.’ But will algorithmically-inspired comms strategies respect the truth?

He turned to neuroscience to argue that our brains function as a series of algorithms, as ‘prediction machines’.

In comms planning, we used to work on the model ‘think, feel, do’ but if you look at the neuroscience, we should be looking at it from the perspective of ‘feel, do, think’.

We respond emotionally, make decisions and then afterwards post-rationalise these decisions. Clearly this echoes the political landscape discussed by the first two speakers.

Our brains are optimised to feel which is why emotional messaging always trumps reason.

Collister’s conclusion suggested that rather than machines being somehow opposed to humans, perhaps being superior, the risk is that AI will better mimic the human brain and echo our deepest traits. Worrying!

The final speaker was Dr Angie Ratcharak, a human resources researcher from University of Greenwich. Her theme was leadership and emotion: how to be a human being in the workplace.

What does it take to be a manager and leader of fellow professionals?

She presented three approaches to emotional leadership, two of which involve acting (is this being honest and truthful?): she talked about ‘surface acting’ (faking emotion rather than feeling it); ‘deep acting’ (feeling the emotions of team members); and genuine emotion (with the risk of loss of control).

Then there’s the problem of the feedback loop. If leaders only receive positive feedback from their followers based on their acting, then this can be harmful to their own wellbeing.

In the real world, leaders don’t choose their followers, so there’s rarely perfect alignment of values.

You can easily see how this dysfunction relates back to the bullshit artists and narcissistic leaders in the political sphere, discussed earlier.

.@GreenwichNickyG is summarising the four presentations and the comments from the discussion thread. She focuses on the 'spectrum of lying'. #MindthePRGap

— PR Place Insights (@PR_Place) July 13, 2022