Read books, ask questions, become media literate, don’t give up, write every day

How to succeed on your MA in Public Relations

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

There are many valid reasons to take a taught MA course in public relations. You might want to pursue something more vocational than the subject you studied for your bachelor’s degree; you might want to experience life in a different city or country; or improve your language skills and cultural awareness; or simply delay leaving education for one more year.

Probably the least likely scenario is that a student sees this as a stepping stone to an academic career – though that’s an option too.

We recognise and welcome the wide variety of backgrounds and experience in any group of students.

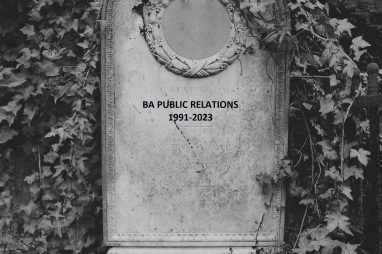

Yet something else is going on within universities in the UK. I’ve previously noted the decline in undergraduate public relations education (you can only apply to study single honours public relations degrees at two universities – London College of Communication within University of the Arts London and Ulster University).

This decline in public relations courses has been offset by the rapid expansion of taught MA courses in public relations, with this growth coming overwhelmingly from international students.

This decline in public relations courses has been offset by the rapid expansion of taught MA courses in public relations, with this growth coming overwhelmingly from international students.

It’s a international phenomenon, reflected in published UK immigration statistics and much discussed in the media and parliament. In the year to March 2023 there were over 632,000 study visas issued by the Home Office, up 34% on the year before. That’s almost 5,000 fee-paying international students for each of the 130 higher education institutions listed in the Complete University Guide 2024 plus there’s the contribution to the wider economy through the cost of their accommodation, shopping, hospitality and travel.

Migration statistics are a political issue in the UK because one factor influencing the majority vote to leave the European Union in 2016 was the promise to end uncontrolled migration. That may have since happened in terms of EU migrants but they’ve been replaced by even greater numbers from non-EU countries. Why short-term student visas even appear in migration statistics is a question for politicians to answer.

It’s always hilarious and baffling to me at the time that the UK Gov wants international students to pay a fortune to come here and study, and the same Gov makes us move mountains and seas to be able to work here – the time the paperwork the MONEY. Like go off, sis.

— Son Pham (@beyondson_) June 11, 2023

There are many arguments in favour of these large numbers of student visas: international students are cross-subsidising the education of home students at a time when student fees have been frozen rather than keeping pace with inflation. And the UK has acute labour shortages that can partly be met by an influx of young people keen to work alongside and for two years after their programme of study, as their study visa allows.

Then there’s the soft power argument. Britain long ago lost an empire; again, part of the Brexit prospectus was about ‘global Britain’. So a generation or two on from independence, the soft power of the English language and a British education still appeals to young people from countries such as Nigeria and India that are themselves important regional and global players. To adapt a well-known phrase about Britain losing an empire and struggling to find a role, you could argue that Britain has lost power but retained influence on the global stage.

Whatever the motivations these large numbers of international students have for travelling to the UK, after the time, trouble and expense of gaining your study visa and reaching the UK, we want you to succeed.

This article has sought opinions from those who have studied on and those who teach on MA Public Relations degrees. We address a range of academic, cultural and linguistic challenges facing international students once they’re in the UK.

Academic

We understand that most of those applying to study an MA in Public Relations will be new to the subject – academically and vocationally. Yet some may have studied a subject (marketing, mass communication or journalism, say) that gives them some background or context. Others will have relevant work experience.

So no Master’s degree can simply be an extended introductory course: you are expected to emerge with some mastery of the subject.

This means moving beyond basic knowledge (for this, you can never compete with Google, Wikipedia and ChatGPT) to being able to make recommendations for future action informed by data and insight.

Whatever your reason for applying to study public relations, you can expect to be taught by subject experts, so the very least you should do would be to show some curiosity about your chosen subject. Your lecturers will be flattered to be asked about their own work experience and professional affiliations and/or about their research interests and publications.

Ask yourself why you applied to study public relations. In answering this, you will be forced to enquire about the subject. Start with a working definition of public relations – and be prepared to join the course with an open mind.

Because for everyone who thinks it’s just publicity, the disciplines of reputation management and crisis management will show that there are many situations when organisations and individuals would prefer not to be talked about.

For everyone who thinks it operates primarily through media relations, open your eyes to the many internal communication practitioners whose focus is on employees and the many public affairs practitioners whose focus is on politicians.

Those who set out thinking public relations is just a part of marketing, ask yourself this. Why is it still taught as a separate discipline within universities? Why are there distinctive professional bodies (such as the UK’s CIPR)? Are customers necessarily a more important group than employees or investors?

For all those who see public relations as a short-term promotional tool (stunts and award-winning campaigns do seem to garner disproportionate attention), ask yourself why it claims to be a strategic discipline and not just a tactical tool.

You may start out thinking ‘how hard can it be?’ After all, we all communicate. So a more interesting question is why communication so often fails. Admit it, you’ve tuned out while a teacher or lecturer has been talking – and that’s in a face-to-face classroom environment. Online communication is more challenging because we’re so easily distracted. Attention has to be earned.

Read books; and learn how to use the library; at a good university, librarians are your friends. Start with core texts and build upwards.

Philip Young is a Senior Lecturer in Public Relations at Birmingham City University. He advises:

Read books; and learn how to use the library; at a good university, librarians are your friends. Start with core texts and build upwards. I read far too many essays that happily quote papers on cat fish breeding in Malawi but appear never to have encountered Tench and Waddington or Theaker, despite repeated unsubtle prompts. Distinguish between blogs of varying quality and peer-reviewed articles.’

Carina Gama offers similar advice from an international student’s perspective:

‘I didn’t do a MA in PR but I did a BA as an international student. It was difficult to adjust to a new country and a new educational system but I did it! My top tips would be emerge yourself in the UK media and political landscape, ask tons of questions (to peers and tutors) and take advantage of the library and the million online resources the university provides. Where I come from I’m not used to having this many resources available so this was a huge cultural shock for me.’

Tom Rouse is a practitioner at Pitch who also teaches, and he also focuses on the need for students to immerse themselves in the media landscape of the country they’re studying in. He stresses the vital importance of media literacy.

‘Media literacy is the most underrated skill in the UK right now, but I think it’s utterly crucial for all students. Being able to explain why Vogue will cover a fashion story differently to a national newspaper will get you a long way. And you’ll get even further if you can then tell me why HypeBeast or a fashion influencer will approach it from yet another angle. This also means developing a healthy degree of scepticism – why is this news, why have the written that angle, and can I trust this source of information are utterly vital questions for a student to ask and be able to answer.

‘My final tip – take every opportunity to ask why. The best students are curious – they don’t just accept that a channel is useful or that a story is relevant. They ask why – what problem is this solving or communications goal is it delivering on.’

Cultural

Raluca Moise from City, University of London talks up the benefits of the ‘culture shock’ experienced by international students.

‘As a PR lecturer with lived experiences in different academic & educational systems (Romania, France, Belgium, UK), I would say that international students adapt very quickly to clearly outlined expectations. The cultural shock is something that enhances adaptability and cultural awareness. The interaction between home-based and international students is always culturally rewarding for both groups, deconstructing their in-awareness and helping to build bridging types of relationships. Academic environments can create meaningful intercultural experiences, which, as we all know, are crucial to today’s PR profession, where the majority of PR practitioners are communicating to international publics.’

There’s the need for a culturally inclusive curriculum combining domestic and international case studies, longer induction ahead of semester 1, socio-cultural (including media and political landscape) training for students and staff.

For Ramona Slusarczyk who teaches public relations at Newcastle University, there’s a need for cultural adjustment by faculty as well as by students.

[There’s the need for a] ‘culturally inclusive curriculum combining domestic and international case studies, longer induction ahead of semester 1, socio-cultural (inc. media and political landscape) training for students AND staff, additional language and academic skills support (eg some students never had to write essays, but only had exams), and learning materials made available way ahead of in-class teaching, to name just a few key adjustments. Here is a superbly insightful study on how PGT students experience a transition to UK academic culture.’

Diane Green, a public relations lecturer from the University of Sunderland agrees that adjustment is needed on both sides:

‘I agree it’s challenging for students and tutors alike. My tip would be for lecturers to embrace students’ experiences, but also to encourage students to immerse themselves in the UK media and social media landscape too to fully understand some aspects of our teaching in practice.’

Miriam Pelusi is originally from Italy. She came to the UK to study an MA in Public Relations at Leeds Beckett University and returned years later to study for a part-time PhD. She writes:

‘Studying in another country and using your second language is a great challenge that in the long-term will make you more resilient, but it’s likely you’ll have moments of discouragement, it happens. Don’t give up and carry on. My tip for success is to keep working on your adaptability skills as you’ll need to adapt to small and big changes. It takes time to learn how things work, so don’t be hard on yourself if it seems that you don’t make progress.

‘Teaching and assessment will be different in the UK, understanding how it works is a big challenge. There will be things that do not make sense to you. For example, thirty is the highest grade in Italy, whereas it’s a fail in the UK. The academic quarter is not a thing in the UK, and unlike the UK there are no extensions and mitigations. My tip for success is to spend time familiarising yourself with the new education system, ask questions as and when needed. Check the course handbook and the academic regulations.

‘Another challenge is to fit into a new academic culture, the academic mindset is different. The way you’ll approach your academic writing will change but it takes time and effort. For example, Italians tend to use extended prose, whereas in the UK you need to go straight to the point. My tips are to read widely (journal articles, newspapers, books); attend academic workshops delivered by study skills support; use an academic phrasebank like the Manchester phrasebank.’

Linguistic

Miriam Pelusi adds:

‘Another major challenge is working in a second language. Be aware of some issues that you might experience, particularly at the beginning like the ‘silent period for second language acquisition’ in which you’ll absorb new words, phonemes but at the same time it will be difficult for you to produce as much. First language interference is another challenge as your first language will influence the way you express yourself in your second language.

‘My tip for language learning is to build your vocabulary; use an online dictionary to check the meaning of words, its pronunciation, and examples of how the word is used in context. Take notes in English as you’re listening to your lectures as it will help you enormously with your listening and writing skills. If you have an oral assessment, you could try recording yourself whilst practicing. Listen to the recording to hear how you sound in English, adjust your pace, pick up errors that you can correct. Practice with a friend.

‘When I started my PhD, I was advised by the Language Learning Adviser at University to read this book:

Swan, M. and Smith, B. (2001) Learner English : A teacher’s guide to interference and other problems. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge handbooks for language teachers).

‘It’s for teachers but I found it very helpful as a language learner because it covers ‘the typical problems and error-patterns of a wide range of learners of English from particular language backgrounds’. For example, English learners who have Italian as their first language will face similar problems. There are dedicated chapters for several languages.’

Experience

Prakriti Roy is a current Master’s student in the UK and our #CreatorAwards23 winner. From Delhi in India, she suggests that students from her home country would benefit from a period of work experience.

Those who come to the UK for a Masters should [first] gain a few years of experience in their home countries, even if it is not in the same stream as their Masters.

‘I strongly feel that those who come to the UK for a Masters should [first] gain a few years of experience in their home countries, even if it is not in the same stream as their Masters. It helps develop a sense of discipline and work ethic and makes it easier to fit into the style of teaching here.

‘In India barely anyone works during their undergraduate degree. As a result, if they arrive here without any work experience, they are thrown into a system that is really alien, considering that they come from a protected environment where family takes care of everything and the style of teaching is monumentally different.’

Martin Agunwa recently graduated from this same MA course and has since gained experience in various public relations roles in the UK. He emphasises the importance of personal branding and networking in transitioning from being a student to an employee.

‘My advice is for students to start early on in their studies to think about their personal brand. This for me means being deliberate in how they use their social media platforms especially LinkedIn.

‘I’ve found LinkedIn to be a useful platform to demonstrate skills, competences and interests by way of the kind of content we put out. More so, although it should go without saying, it’s good platform for networking.

‘I’ve connected with almost every hiring manager on LinkedIn immediately after an interview whether it was successful or not. The reasons are simple – 1. I like them to see my profile (if they haven’t). 2. I’d like them to remember me.

Finally, I’d suggest that students participate in industry events organised by the PRCA & Chartered Institute of Public Relations. And connect with industry professionals. A lot of professionals are willing to support students.’

Teela Clayton is unique among the people I spoke to in having recently been a student on an MA Public Relations course which she now teaches on (she’s also working towards a PhD). She focuses on the need to become an accomplished writer:

‘“Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.” This mantra, pilfered from Picasso himself, has been my go-to since embarking on a teaching career *some* years ago. It is wonderfully ubiquitous, from carpentry and cricket to cookery and er…cubism. But the area in which it holds most weight is writing.

‘The CIPR State of the Profession study cites copywriting and editing as one of the major skills used every day by professionals working in Public Relations. But so many students embark on the Master’s journey with scant knowledge of the rules and limited practice of different professional genres. So my advice is simple: write.

‘Write every day. Write poetry. Write in prose. Write letters to your friends and family. Write lists. Write about your journey (in life/to work/through education, delete as appropriate). Write reviews of your favourite restaurant. Write missives filled with idioms and superlatives and incorrigible promises and expectation and longing. Write stories that awaken the senses and burden the heart. Write recipes that open doors to wondrous exotic lands thick with spices. Write a blog. Write a thank you note. Write that thing. Write. “A writer is someone who has taught his mind to misbehave,” says Oscar Wilde. So learn the rules. And then break ‘em.’