Report: Charity Comms Psychology of Communication conference

About the author

Kevin is a co-founder of PR Academy and editor/co-author of Exploring Internal Communication published by Routledge. Kevin leads the CIPR Internal Communication Diploma course. PhD, MBA, BA Hons, PGCE, FCIPR, CMgr, MCMI.

More and more people are becoming interested in understanding how to use psychology in communication planning.

The evidence for this was a bumper turn out for the Charity Comms Psychology of Communication Conference in London on 28 June.

It has often intrigued me that relatively few public relations and communication management practitioners have a psychology background. Understanding how people process information and form attitudes that affect behaviour are fundamental to practice. And yet there still seems to be little crossover from academic psychological research into communication management. (For a deeper discussion on this issue see my conversation with Dr Heather Yaxley here).

Given this background, it was heartening to see a conference that was dedicated solely to the psychology of communication. This is the first time I have seen this happen. It may be a sign that the work of the Behavioural Insights Team is starting to have a wider impact in the comms world. Or it may simply reflect the nature of charity comms with its natural focus on fundraising and social issues. Whatever the reason, it is hopefully the start of a broader movement that explores the psychology of communication management in more depth.

This review is based on the keynote opening presentation and four of the twelve optional breakout sessions that were available on the day. Some of the presentations from the conference can be viewed here.

One of themes that presenters highlighted was social learning, or as Mark Earls (@herdmeister) describes it ‘Copy, copy, copy’. To illustrate the point, he got delegates to stand up, hold hands with the person they were sat next to and then get them ‘off the ground as much as possible’. Within seconds nearly everyone was jumping up and down…because they just copied everyone else. The influence of social learning is well established in psychology and is often associated with the work of Albert Bandura. However, this quick, fun, icebreaker missed the point a bit as there were not really any other obvious ways to get off the ground.

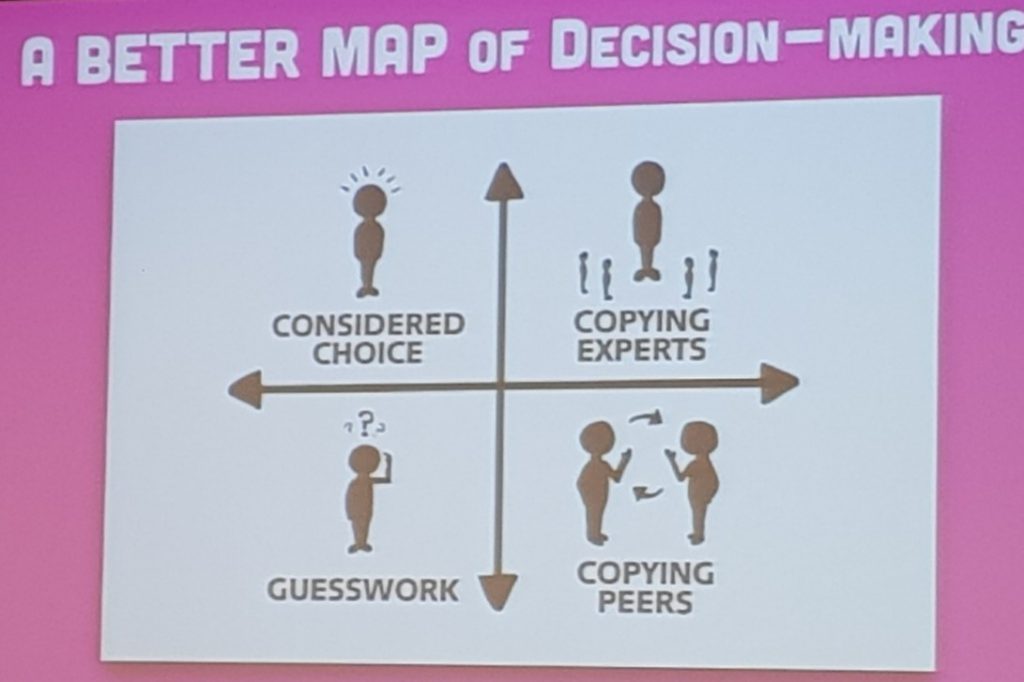

Earls suggested that you can break decision making down into four biases: copying experts, copying peers, considered choice and guesswork. He argued that people don’t think much at all, we are impulsive and intuitive and then think later. However, this is really dependent upon the situation. As the well-known elaboration likelihood model illustrates, we do sometimes think hard.

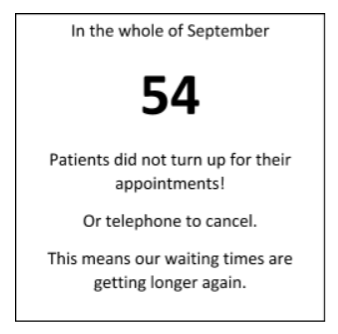

Social norms are often simply understood as the expectations or rules that exist in society. As David Hall (@FreelanceBrain) highlighted, we’ve become accustomed to thinking that a full restaurant is likely to be better than a half-empty restaurant. We’ve also all seen the message in hotel rooms about reusing towels. Hall suggested that a ‘save the environment’ message was less effective than the ‘75% of guests in this room participated in the towel reuse program’ message. Making it personal seems to have a much stronger impact. However, attempting to use social norms can be counter-productive. Hall provided an example of a GP surgery using a poster with the following:

The negative takeout from this is more likely to be that so many other people are missing appointments that it won’t really matter if I do.

Hall provided a handy social norm message generator:

80% of people

Most people

More and more people

Like you

In your community

In your city

Do (be specific)

However, watch out! Credibility is important, especially if using a percentage. On a further note of caution, Hall highlighted how a nudge campaign to get walkers on the South Downs Way to be more polite attracted negative local media attention, with it being called a waste of money.

A key theme of the conference was the basic notion that you have to understand motivations to change behaviours.

Mats Postema (@PennockPostema) provided some interesting examples of how nudges can be used to influence behaviour. Postema argued that we are generally bad at long term thinking. Applying this to healthy eating in a sports centre restaurant resulted in giving athletes a card to pre-order their food and this led to an increased take-up of a healthy food choice.

Tim Hall and Bijal Rama reminded delegates about the importance of priming which they described as a process whereby exposure to one stimulus influences a response to a subsequent stimulus without conscious guidance or intention. An example of this is reminding a prospective donor of a previous donation increases giving. But context is key here. Messaging on organ donation in Michigan was focused on outlets most popular with women as they are central to family decisions about organ donation.

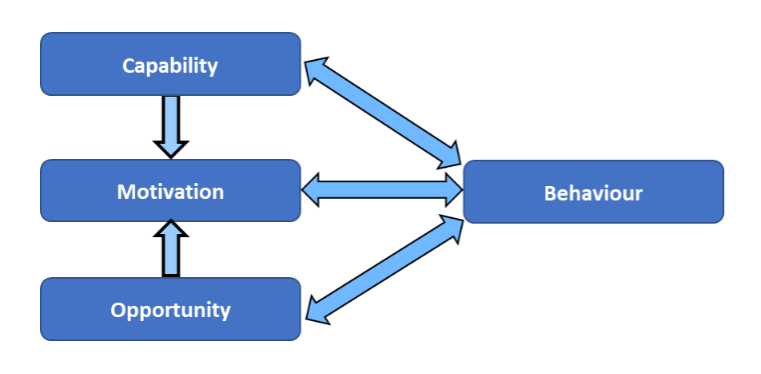

Although the breakout sessions that I attended were interesting enough, it was Kate Brennan-Rhodes (@kate_brennan) who addressed the key point about how to incorporate psychology into your comms strategy. As Kate stressed, communication management people are good at doing information, but that is just one component of an effective strategy that leads to behavioural change. Kate’s simple Com-B model is a good reminder of how to think more about behaviours:

When applied to the Think Bike, Think Biker campaign, ‘capability’ can be related to motorists not seeing bikers; ‘motivation’ can be to humanise bikers in the minds of motorists; and ‘opportunity’ is when driving.

Kate had two other commendable mantras. The first is that tactics are never just ‘comms’, they should be seen as a continuing journey. And the second was ‘test, test, test’. Amen to that.

And I would add that we should always research to assess the situation and understand motivations and then develop meaningful communication and behaviour objectives. I suspect that Kate is a rarity in the public relations and communication management world as she says she ‘loves to draw up testing plans’. Testing would go some way to avoid much meaningless and ineffective communication that wastes money.

In summary, this conference is a welcome addition to the programme of events in the UK with its dedicated focus on the application of psychology in communication management. It feels that the occupation is still often only at 101 levels of understanding psychology and there is so much more that could be learned. But this is a great initiative and the interest shows that it is a topic that resonates with practitioners.