Review: Poles Apart

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

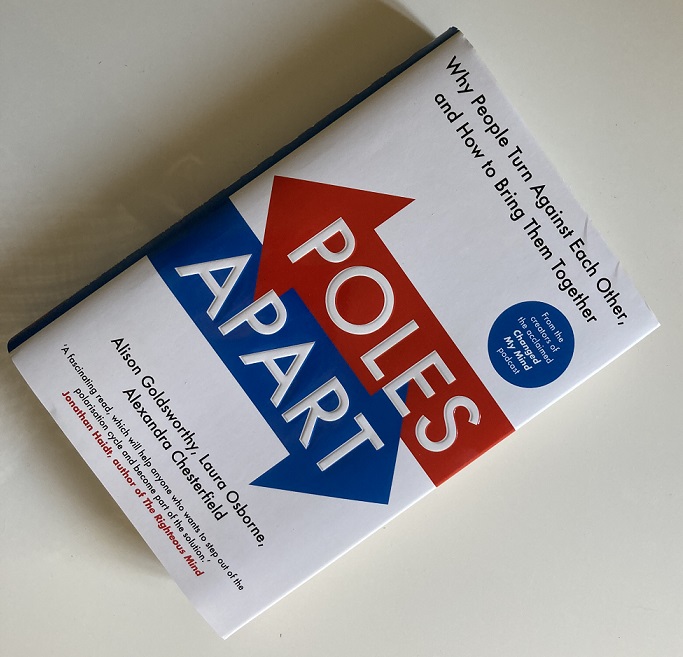

Poles Apart: Why People Turn Against Each Other, and How to Bring Them Together

Alison Goldsworthy, Laura Osborne and Alexandra Chesterfield

2021, Random House Business, 301 pages

This is an important book, addressing the question of how free access to information has not been met with greater understanding, but rather with ignorance and division. It’s also a useful book, providing a crash course in psychology and anthropology.

It’s some achievement: to write such a well-researched, well-reasoned and serious-minded book about our unreasonable behaviour!

This book takes the long view of human behaviour. It’s a reminder how deeply-embedded are our responses to threats and uncertainty, and that it’s too simplistic to blame it all on Facebook and Twitter.

We form groups, tribes, because we’ve always needed to do so to survive. Loneliness hurts. As the authors note, ‘During the 2020-21 Covid-19 pandemic, when millions were forced to keep apart from one another and observe social distancing, it was estimated that almost a fifth of the UK population required some measure of mental health support.’ What’s more ‘The United Nations defines as torture any period of solitary confinement lasting more than 15 days.’

Our group allegiances prevail over rational, individual choice. ‘In short, we distort reality to meet our fundamental human needs – belonging, reducing uncertainty, increasing self-esteem and status within our groups.’

Not only this, but as Harvard psychologist Gordon Allport wrote after the second world war: ‘Whenever [times] change for the worse… in-group boundaries tend to tighten.’ Conflict theory tells us that when resources are scarce, groups will become more competitive with each other and prejudice and discrimination will multiply.

Nor do resources even have to be scarce: the mere perception of scarcity is sufficient. And it’s not hard to list those scarce resources that should worry us: money, security, water, energy, clean air.

‘Our group identities act as a kind of heuristic – a rule of thumb or short cut designed to help us process and evaluate information quickly…. Such a strategy is one that requires little effort, and so saves precious cognitive resources.’

‘It comes as no surprise that we look to strong leaders in uncertain times.’ Others have noted the rise of ‘illiberal democracy’.

The authors remind us that ‘narratives and conspiracy theories that polarise are nothing new’, citing the long history of anti-semitism stretching back to medieval times.

What’s changed in the social media age is the speed at which messages can be amplified.

So much for the problem. What solutions can the authors propose?

Could stronger political institutions have helped prevent the former Yugoslavia from splitting and turning to violence (becoming polarised along national, ethnic and religious dividing lines) they ask?

Communicators will find the section on message framing useful. Telling people to eat less meat can be counter-productive, since it implies they are doing something wrong which challenges their positive sense of self. Yet if the message is framed neutrally as ‘meat consumption has gone down by 12% since 2008’, this suggests that people like you are cutting back on meat consumption.

The authors conclude this section: ‘it is difficult to reshape groups in such a way as to reduce polarisation. But that doesn’t mean it is impossible.’

What does make us change our minds? ‘Not, as a general rule, facts.’ Nor should we necessarily seek to win the argument.

‘A zero-sum, winner-takes-all mentality makes both sides think that if the other side wins, they lose.’ It’s better to seek to understand than to seek to win.

The book ends with a postscript listing the steps we can take to reduce polarisation, to turn ‘us and them’ narratives into stories we all can share.

They contain lessons in empathy and negotiation that will be useful to all communicators. And yet the pressure continues on many in our business to achieve links, coverage and engagement in a world of short attention spans that almost inevitably forces colleagues to heighten emotions and court controversy. We’ve always had polarisation, but we haven’t always had social media algorithms.

Cambridge Analytica gains one passing mention, and does not even make it to the index. I’d have welcomed their assessment of this scandal, and also of the use of troll farms to sow uncertainty and stoke division.

The Bell Pottinger scandal, by contrast, is well handled. Most of the interest in public relations circles was in the firm’s expulsion from the PRCA and its subsequent collapse. Here, we’re reminded of some of the dirty tricks they’d employed in South Africa on behalf of their client, the Gupta family. ‘Playing on political fears to pursue business interests, it involved setting up 200 fake Twitter accounts that sent out more than 220,000 tweets with hashtags such as #whitemonopolycapital and #respectguptas. Websites called WMC [White Monopoly Capital] Leaks and WMC Scams were created.’

It’s good to take the long view, but the authors seem to have turned a blind eye to the state of social media. They are perhaps too reasonable and too academic in their approach, and lacking in journalistic flair. Carol Caddwalladr could have filled in these gaps, but perhaps she’s working on her own book?

The impressive authors, all from the UK, are Alison Goldsworthy, a political campaigner (Liberal Democrat), Alexandra Chesterfield, a behavioural scientist (who has served as a Conservative councillor) and Laura Osborne, a professional communicator with a background in public affairs and corporate communication. They are behind the Changed My Mind podcast and the Depolarization Project.