Review: The Art & Craft of PR and Myths of PR

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

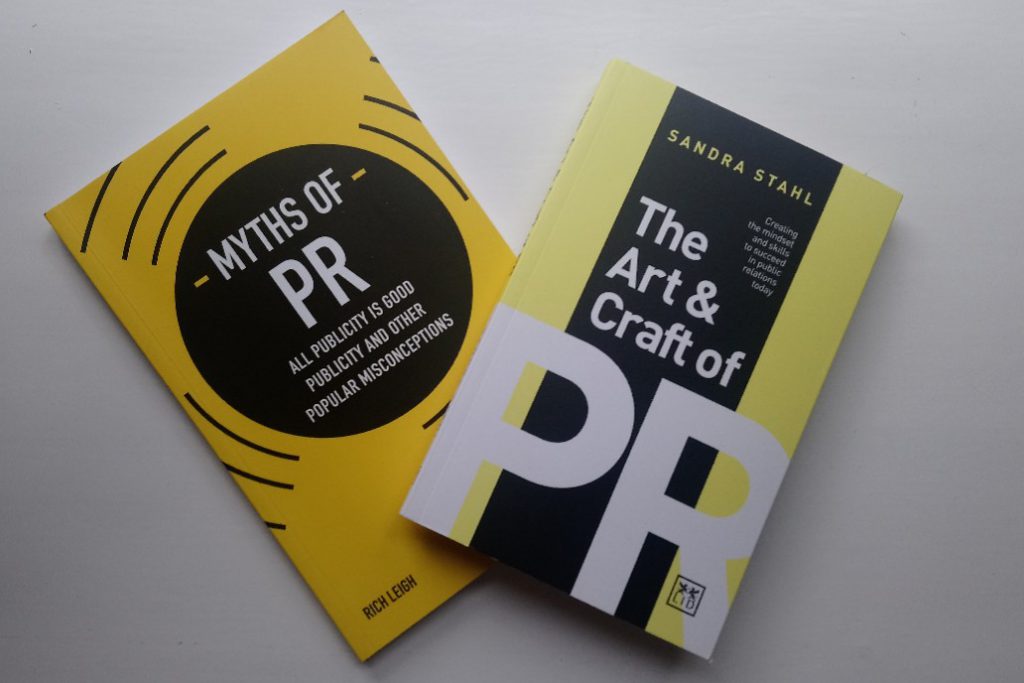

The Art & Craft of PR: Creating the mindset and skills to succeed in public relations today

Sandra Stahl

2018, LID Publishing

Myths of PR: All Publicity is Good Publicity and Other Popular Misconceptions

Rich Leigh

2017, Kogan Page

We’ve recently reviewed several new academic texts, so I thought it time to take a fresh look at public relations through practitioners’ eyes.

One book is new: newly published, and from an author I’d not heard of. The other is more familiar to me. One is from the US; one from the UK. One from a woman; one from a man – though both are consultants.

There’s a school of academic thinking that dismisses practitioner books as ‘instrumental’ (ie merely serving the purposes of management) and which looks down on skills-based approaches. I don’t share this view, but nor do these authors fall into either trap.

Sandra Stahl’s approach is to look top-down rather than bottom-up at the public relations role. She’s as keen as any academic (I note that she also teaches graduate students in New York) to position public relations alongside other disciplines and to try to paint the bigger picture.

Her motive comes clear right at the end of this short book. In the epilogue, she writes:

‘I wanted to encourage students of philosophy, psychology, human behaviour and other social sciences to feel they have a path into PR. And conversely, for journalism, PR and media students to expose themselves to a wider range of classes, such as business and business management. The industry needs all of these skills in order to thrive and continue providing perspective and distinct worth.’

In other words, public relations is a complex activity drawing on different disciplines that needs smart people.

Her top-down perspective can be seen from some chapter headings: ‘PR has no boundaries’; ‘Don’t just listen; really hear and include’; ‘Inspire to change behaviour’.

The chapter ‘Think attraction, not promotion’ is excellent. ‘Promotion is one-way communication, a ‘push’ of information… It is, essentially, a demand to be heard and seen.’

‘Promotion asks for stakeholder time, attention and consideration, without regard to their schedule or need. As a result, promotion can be seen as irritating.’

‘Attraction is different. Attraction is mutual. It is a joint desire to connect.’

This is not new, perhaps. Seth Godin’s Permission Marketing made a similar argument in 1999, but Sandra Stahl is a gently persuasive guide. She writes without ego (though there are a few ‘war stories’) and allows other senior practitioners to have their say throughout the book.

The chapter ‘Perfection is overrated’ had my favourite of her ‘war stories.’

Her team was facilitating a symposium for a pharmaceutical company client. They had managed to book a prestigious and in-demand keynote speaker, who lived up to expectation. The problem was, this speaker had enjoyed the hospitality too much and almost slept through the keynote appointment, which caused alarm among her team.

‘Was this project a success. It certainly seemed so. Did it achieve its objectives? Yes, without question. But was it perfect? I think we all know the answer to that. Perfection is not a reasonable measure for most professionals or assignments.’

The paradox here is that we need smart and intelligent people in public relations. But it’s not a job for control-freaks as we’re not puppet masters who control others’ thoughts and actions. So it also demands people with agility and persistence.

I don’t agree with one of the reviewers who said that she ‘has written a must-read primer for anyone considering a career in PR.’ It’s more advanced and sophisticated than that (just as public relations is more advanced and sophisticated than many believe).

Which leads me to a significant book addressing the many misconceptions surrounding public relations. Rich Leigh addresses 18 myths.

Myth 7: PR is glamorous. ‘Public relations is routinely fictionally depicted as being a glamorous and/or hedonistic career, full of people with questionable ethics.’

‘As long as this myth of PR as being one party is allowed to prevail, young people around the world are making the decision to spend years of their lives and varying sums of usually-borrowed money on their education to embark on a career that looks nothing like they think it does.’

If Sandra Stahl’s book is deceptively sophisticated, Rich Leigh’s is a choice read for those considering embarking on a career – or a degree course – in public relations.

He’s an ideal author, since he’s a (still) young high-achiever who became a teenage father, never went to university, and worked his way up the ladder into business ownership in his twenties (an age when some graduate students might still be disabusing themselves of visions of the imaginary Samantha Jones lifestyle).

Myth 10: You have to be an extrovert to succeed in PR. ‘There is a misconception that PR professionals have to be charismatic extroverts.’

‘I am, by nature, an outgoing person. I’m sociable, unduly confident in new situations, often outspoken and…. sometimes an idiot,’ he writes.

Citing Carl Jung and Susan Cain, Leigh goes on to list some of the traits introverts can bring to organisations. Listening comes first, which echoes the emphasis placed on this trait by Stahl.

Most controversially (I remember the discussions when the book was first published), Myth 18 tackles the gender pay gap. Leigh cites recent evidence from PRCA, CIPR and PR Week surveys to show that men are paid more than women in public relations. He takes this in an unexpected direction:

‘These are the industry figures that stick in your mind. Students will be taught them and industry entrants will begin their careers believing they are being held back. Two-thirds of PR industry employees in the UK are women… so that’s a huge number of the industry affected. Only… these figures aren’t telling the whole story.’

‘Headlines and Twitter-friendly takeaways like ‘women in PR earn £15,040 less than men’ help nobody, because they’re inaccurate and liable to spread like wildfire.’

‘They are inaccurate because it is a simplification of a complex issue, compounded by the fact that the necessary questions to determine the pay gap have not been asked.’

It’s also rather a long and complex chapter, but it reveals another truth. Aren’t PR people meant to simplify complex stories and turn them into headlines? Or is that another myth?

Sandra Stahl argues for critical thinking in public relations, and Rich Leigh is demonstrating it in this example.

It’s easy to accept sources and repeat headline findings (particularly so when virtue signalling on social media). But as advisers with a duty to act responsibly and ethically, we also need to challenge received wisdom and be willing to go against the crowd.

It’s been an enjoyable detour. Thanks to both these authors, I feel much more positive about public relations, and optimistic for its future.