Review: The Indispensable Community

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

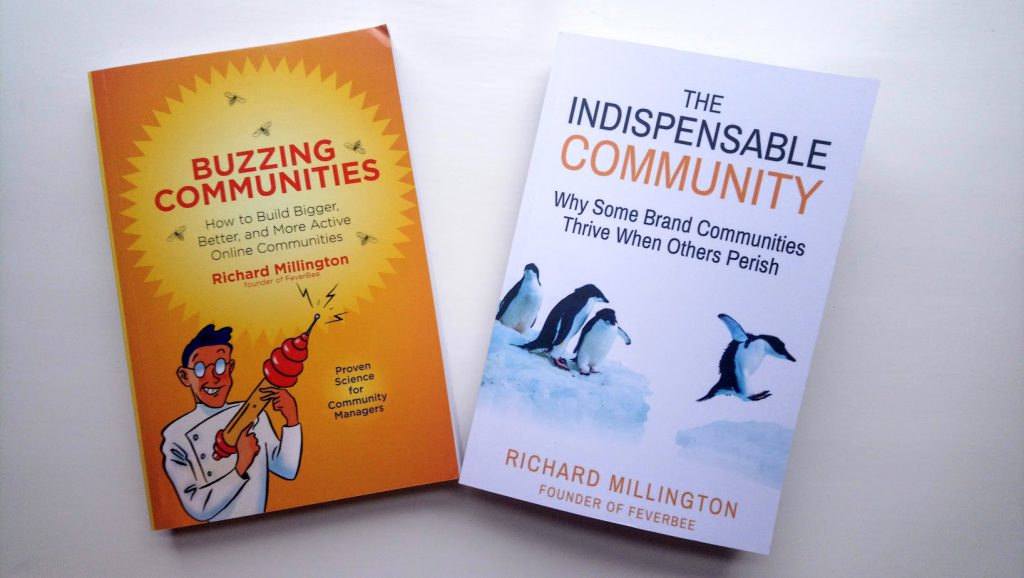

The Indispensable Community: Why Some Brand Communities Thrive When Others Perish

By Richard Millington

FeverBee, 2018

Advocacy is the desired outcome of community engagement

Community management is not a new idea. Nor does it require technology. But there’s been growing interest in the field in the age of the web, social media and smartphones. Wikipedia (founded in 2001) is a prime example of a volunteer-run online community that serves a public good rather than seeking private profit.

This is a useful start point because it explains where Richard Millington sees community differently from many in public relations. His starting point is that a community should serve the interests of its members and be self-supporting, rather than sponsored by or serving the interests of a business or brand. Meanwhile, communities should be measured not on members or engagement, but on demonstrable return on investment (ROI).

This is the ground covered in Richard Millington’s first book, Buzzing Communities, published in 2012.

The Indispensable Community is his recently-published follow-up book. It shows his thinking has evolved and he’s now ready to reconcile the interest of brands and the interests of community members.

He opens by telling the story of a tech startup, Fitbit, that first embraced its online community as a means of managing tech support, and then as a way to crowdsource marketing ideas and product improvements. Many have tried, he notes, but few have succeeded as well as Fitbit. Why should this be?

‘With today’s technology, and a generation that has grown up digital, there should be a lot more indispensable communities than there are today… It’s a lot easier to launch another Twitter account than to take a group of customers aside and build something special.’

This book is written in business-book style. Millington tells a fresh and compelling story, then follows up with the lessons that can be learnt from the story. (It’s the opposite approach to an academic textbook, which would lead with the theory and then perhaps choose an example to illustrate or challenge the theory).

The book itself tells a community story, since the author crowdsourced ideas and welcomed comments on drafts.

He’s become a very accomplished writer, too (this is noteworthy, since he graduated with a marketing degree from University of Gloucestershire only ten years ago). Since then, he’s taken an entrepreneurial career path, launching and leading his FeverBee online community management consultancy, working with clients and delivering training worldwide. The book reflects his global perspective.

In reality, he has more than a decade’s experience since he’d been working as an online community manager since his teenage years. So he’s a poster boy for turning a passion into a life’s purpose.

As presented here, one purpose of community engagement should be advocacy. ‘The most successful advocacy programs begin with the members most likely to advocate for the organization and gradually expand the circle from there. But finding advocates is only half the battle; keeping them is harder.’

The answer to this riddle may involve a combination of micro-factors (points and prizes for engagement by community members) and macro-factors (‘a sense of tribal identity’).

At this point in the narrative, I’d have welcomed some interviews with some of these self-appointed advocates, but Millington continues with the organisation-led narrative (which is probably most useful for his intended community manager readers.) Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody from 2008 contains the best explanation I’ve read for what motivates community volunteers (including those involved in open sources coding projects).

I’d also have welcomed some examples from sectors other than technology and gaming. Virtual communities are the focus here, but there are valuable lessons to be drawn from communities that blend online discussions with real-world relationships (football fans, charity volunteers and activists would be others).

Customer support is a win-win example where communities can improve service while cutting costs. Millington’s example is the SIM-only mobile phone service GiffGaff that says that questions posed in its community are answered in an average of 90 seconds.

Millington reconsiders the role of so-called ‘lurkers’ – the most common type in communities – and renames them ‘learners’. Communities should not only be designed for advocates or for leaders, but for learners too.

This leads to an insightful two-by-two grid comparing ‘learners’ with ‘posters’ based on an analysis of what they know they’re looking for/sharing and what they don’t know they’re looking for/sharing. Social norms is in the don’t know/don’t know box (a real world example would be how dress codes evolve at work by the example set by colleagues). ‘A social norm is what the majority of members (or those considered peers) already are doing.’

The engagement trap

A discussion of value revolves around what Millington describes as ‘the engagement trap’ (when the community is measured by active members, posts, likes, shares etc). ‘Anyone whose job is measured by engagement metrics is caught in the engagement trap… Once a community begins to fall down the ladder of valuable contributions, it’s very hard to climb back up.’

In a useful parallel for public relations practitioners, he explains that advertisers seek engagement whereas community managers seek behaviour change. Tools such as Google Analytics were designed to answer the former, but are unable to help answer the latter problem.

So what is a community worth? It’s like trying to value the impact of public relations. ‘Unless a community has meaningful goals, it’s impossible to know which behaviors matter. You can’t hit a target that doesn’t exist.’

The biggest paradox of all was that research showed that volunteer-led communities were more successful than those with full-time community managers and the resources of an organisation. This is partly explained by the passion that volunteers bring to their projects. It’s partly explained by the low risk of failure involved in volunteer-led communities (a theme of Clay Shirky’s book).

‘Communities created by professionals get tangled up in a web of their own restraints. They often make the communities about themselves.’

Having read this book, I’m more convinced than ever that community management and public relations are closely connected disciplines. I suspect the author may have shifted his thinking in this direction too (since PR teams do more than write promotional press releases).

Certainly, the sections on objectives, strategy and evaluation will all resonate with PR teams who face the same challenges. It might also help solve a problem Millington addresses – that there aren’t many ‘chief of community’ roles in the world. Community objectives are consistent with public relations objectives, so logically the boss would be a ‘chief communications officer’ or equivalent.

The author has come a long way since publishing Buzzing Communities in 2012. He’s developed admirable expertise since graduating in 2008. There’s so much we can learn from him – and this is a wise and valuable book.