Review: Understanding Public Relations

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

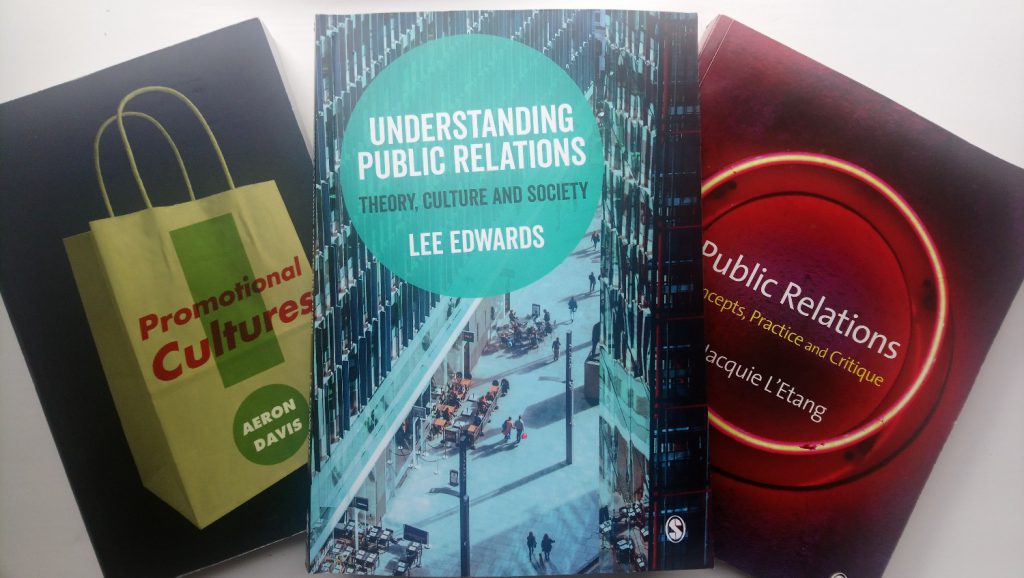

Understanding Public Relations: Theory, Culture and Society

Lee Edwards

2018, Sage

Public relations has many critics. For outsider critics (media sociologists prominent among them) it’s a malign and undemocratic force that can do no good. Insider critics are more interesting: they understand the industry but prefer to look at it outside-in rather than inside-out.

Prominent among these insider-critics, Jacquie L’Etang seems to me to be the academics-academic, though she is less widely read or cited by practitioners. Since her retirement, the baton of leading critical scholar has been passed to Lee Edwards, now of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

We know that scholars can display mastery of narrow subjects; this book shows one scholar spreading her wings and tackling the big questions. This is her manifesto for a socio-cultural approach to public relations.

The starting point for this text is the ubiquity of public relations. PR people are no longer the ‘hidden persuaders’ of the past, but operating in public to maximise their persuasive power.

‘In this book, I argue that understanding the importance and influence of public relations in the contemporary world is best achieved by examining its effects on society and culture. I consciously depart from the functional approach to studying public relations, which tends to focus on its role within organisations.’

Edwards follows Aeron Davis in placing public relations within the promotional industries, and explores it alongside branding and advertising.

‘In contrast to both branding and advertising, public relations deals with more discursive forms of communication in order to persuade…. Public relations is the only promotional profession that engages in behind-the-scenes work to ‘coach’ organisations into appropriate communication.’

Chapters cover discourse and power, political economy, the public sphere, globalisation, race and class, and feminism. One chapter addresses ethics and another turns inwards to look at the occupation.

‘Public relations fits into the category of knowledge-based occupations, alongside other modern occupations such as management consultancy, project management and recruitment.’

Yet there are problems with the professional project, as she identifies. ‘In general terms, the notion of professionalism is itself a classed term, given the historical association of professions with elite occupational groups and social status.’

The chapter on ethics is an important one for practitioners and industry bodies.

‘The vagueness of ethical principles in public relations is due to the fact that the context for practitioner decision-making is increasingly complex and there are many different ways of approaching ethics in public relations, none of which has a clear advantage over the others.’ Yet ‘for any profession, engaging with ethics is an ontological necessity, essential for shoring up claims of professional morality.’

The author picks her way through what ‘has become a polarised debate about whether public relations is good or bad for society and democracy.’

The context for this study is neoliberalism – the dominant force in politics and economics in the past few decades. The author shares a widely-accepted narrative that the growth of the public relations industry has coincided with the advance of globalisation and neoliberalism, and the introduction of market concepts into the public sector.

I described this as a manifesto, and had expected a polemical book (having anticipated the focus on race and gender and discourse around power). What we have instead is a balanced and nuanced read. (‘Public relations cannot be definitively framed as positive or negative in society and culture, since the power that it generates for different actors depends on the contexts in which it is deployed.’) This might make it less appealing to the general reader, but it’s much more useful for advanced students and educators, for whom this book will serve as a useful reader. There are 40 pages of references in a book that’s little over 200 pages long, so it’s a valuable guide to important sources in and around the field.

This is an important book. Not a must-read, as few practitioners will have the patience, but I predict it will become a milestone text that does just what it promises on the cover – help us to understand public relations in its wider context.