Selling our stories to the media

How the busier-than-ever newsroom presents a golden opportunity for the press officer

About the author

Kathy Peart prepared this article as part of a CIPR Professional PR Diploma assignment while studying with PR Academy.

American psychologist, Jerome Bruner, found we are 22 times more likely to remember a fact when it has been wrapped in a story. However, in our digital world, where instant gratification comes in the form of 10 second videos, 140-character tweets and endless (yet, often hilarious) memes – we are all easily distracted and so, our storytelling is more important than ever.

In terms of the media, we’re all consuming more news content than ever before but the stories we engage with need to grab our attention quicker and be interesting enough to keep us engaged.

As a result, journalists are working harder than ever before to keep their audiences ‘tuned in’.

Newsrooms are understaffed and over-pressured, with reporters striving to deliver multimedia stories, across multiple platforms (TV, radio, online articles and social media). A study, carried out by Perspectus Global in 2022, found a third (35 percent) of ‘time-poor’ journalists wish press officers would ‘realise how busy they are and adapt their pitching techniques accordingly.’ With such pressures on journalists, how a press officer shapes their content could be more vital than ever, and it could be the make or break as to whether their story gets covered or thrown in the (virtual) bin.

Having worked in multiple busy newsrooms in recent years, myself, I can vouch for what journalists today are looking for – a great story, great content to tell that story, and meaningful delivery of that story.

The story

While the way we consume content might have changed, the fundamental thing journalists are looking for has not – a great story that will keep people interested. One of the most frequent requests from journalists who took part in ‘Network Rail’s Transport Journalist’s Survey, 2021’, was for more ‘human stories’.

You haven’t got to try very hard to find research that backs the power of a great story. A study at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, in California, found that when people listened to pitches containing facts and figures, only 5% could recall a statistic. In comparison, if the pitch was told as a story, 63% remembered the detail. In his book, Tricks of the Mind, Derren Brown, discusses techniques he uses to remember long lists of information – by creating stories that link each part together.

At journalism school, I was always taught that a story should speak to a reader/viewer in one of four ways: via their heart, their wallet, their health or humour. In his book Lead with a Story, Paul Smith touches on the importance of the rhetorical concept of ‘pathos’ in story-telling, citing ‘positive emotions’ as key-players to a good narrative. Emotion in others can help raise awareness of worthy causes and demonstrate the human impact of real-world issues – this can be true of any story, positive or negative.

Human interest stories, put simply, can give readers something fun, amusing, emotional or thought-provoking to engage with.

But what if your industry doesn’t lend itself to ‘human interest’ storytelling? I argue there is always a way, and we shouldn’t be leaving it to the journalist to find that angle.

The public sector as a case study

The problem that public sector press officers face is their ‘stories’ are often very niche, data heavy or difficult to evoke emotion from. Communicators in this field have the exciting task of making transport, infrastructure, government policy and law enforcement stories sound sexy. As if that isn’t hard enough, they’re also having to carefully manage their organisation’s reputation alongside public and stakeholder expectation, while also justifying spending their hard-earned taxes. It can be tricky to navigate.

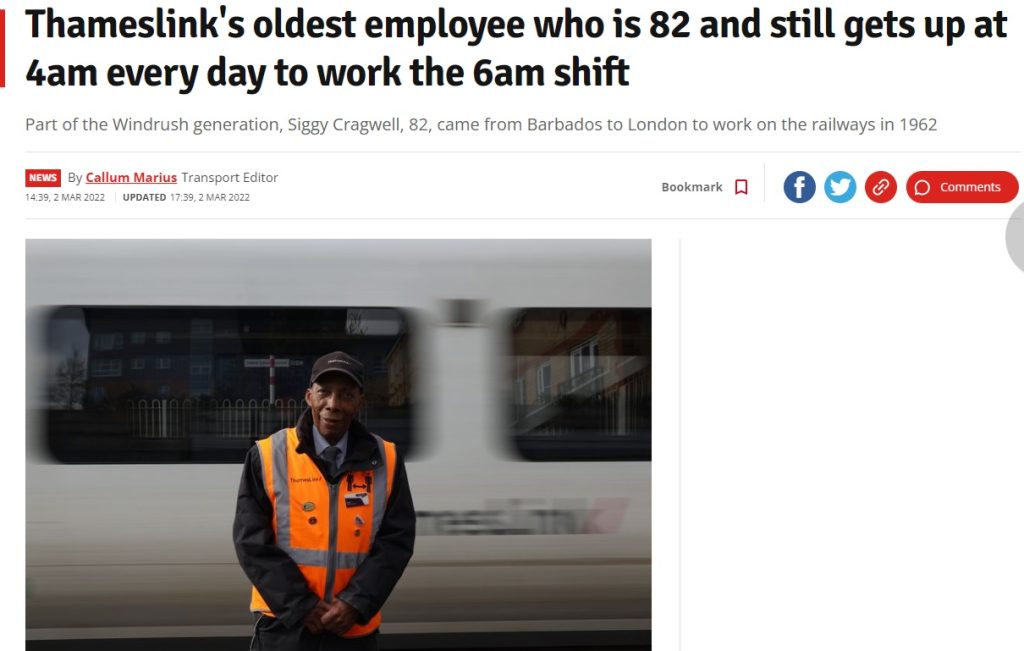

However, some public sector organisations are much better at storytelling than others. For example, Thameslink recently did some fantastic comms, promoting how the company is a great place to work – but there was no self-gratification involved. Instead, the story was told (in a roundabout way) by their most enthusiastic, veteran member of staff, 82-year-old Siggy Cragwell.

Another example is a story about delayed refurbishment works on a railway bridge in North Wales which was reported in The Times newspaper. A story that might not have had any news coverage, or perhaps, even, negative coverage, became a reputation booster for Network Rail, as the media ran with the story of how the organisation is dedicated to protecting wildlife.

The fundamental tool in media relations is the press release, as it remains an important source of reliable information for a journalist to base their story on.

Heather Yaxley talks about how, as communicators, we’re great at getting the ‘word’ out but there is a gap for ‘multimedia reach’ in PR comms. It’s still true, as Bradford Fitch highlighted in 2012, that the fundamental tool in media relations is the press release, as it remains an important source of reliable information for a journalist to base their story on and, as discussed, a great story can be very eye-catching. In a world of ‘fake news’, perhaps the press release is more important than ever but in the 21st Century, it is definitely not enough to earn you the coverage you are looking for.

Great Content

It’s not just broadcast media who are looking to visually tell stories these days. Online newspapers and social media channels are crying out for video and imagery to enhance their output, yet, according to the CIPR’s 2018/19 ‘State of the Profession’ report, the ‘changing social and digital landscape’ was rated the number one challenge facing the profession. I argue that the digital era is not a challenge for comms professionals but an opportunity to enhance their skillset, boost their storytelling and, as a result, get better endorsement from stakeholders and journalists.

According to the latest Cision’s 2021 Global State of the Media Report survey, 85% of journalists used imagery supplied to them with a press release, while 45% said they used video supplied in their coverage. The world moves a lot quicker in the digital age, so speed is prioritised in the gathering and sharing of information in the newsroom. This has, naturally, led to a rise in the use of user generated content (UGC) in the news. There’ still a craving from editors (and likely always will be) for first-hand accounts, behind-the-scenes footage and instant news, from otherwise inaccessible places. Time pressure on journalists can work to the press officer’s gain if we train ourselves to make the content that supports our press release readily accessible. Of course, by creating our own video content we’re also able to use it on our own channels – boosting our reach and engagement with stakeholders.

Since switching from journalism to media relations, most stories I’ve written that have achieved national media coverage have been the ones that include drone and/or timelapse footage, or ‘behind-the-scenes’ footage I’ve filmed, along with high-resolution images.

Drone footage has, for many years, been highly sought after by journalists, as discussed in 2015 by Press Gazette. Drone footage can help give your audience a different perspective or a different emotion. Remember the days when the only way to get aerial footage was if the newsroom had a helicopter? Drones are now an essential storytelling tool for the modern-day journalist, and this should also be the case for the modern-day comms team if we want to tell me innovative and insightful stories.

There’ve been instances where I’ve argued why I won’t publish a press release until I have a range of great digital content – because it’s the whole package of content landing in a journalist’s inbox that is going to boost the chance of getting that coveted coverage. That packet of content needs to include great imagery, spokespeople availability and don’t forget about radio – pre-recorded audio clips are a must for those big stories. It all circles back to the press officer needing to think more like a journalist and taking a step back to picture how easy it is for different news outlets to tell our story with the content we’ve provided.

As highlighted by Deitrich’s PESO model, there is great value in using all four types of media – paid, earned, shared and owned – to boost engagement with journalists, stakeholders and the public. Creating our own media means we can control our narrative and publish content on our own channels. This gives us somewhere to signpost people when we share our content on social media – a hub on information which can drive our readers/viewers to other content we own. When our digital content is good enough it will get shared. Support for your content could be a ‘favourite’, a ‘like’ or a click on a link – every little helps to spread your story more widely.

Meaningful delivery of the story

If we look at the ‘Press Agentry’ model, as identified by Grunig & Hunt in 1984, we can see why this method of story delivery is no longer favourable and it can explain why, in previous years, there has always been tension between journalists and media practitioners. As historian Eric Goldman put it – the press agentry model in the early days was known as “the public be fooled”. Media relations practitioners are seeking editorial endorsement, while journalists are conscious of their duty to report impartial news that interests their audience. That’s why it’s more beneficial for the press officer to adopt Grunig and Hunt’s ‘Two-way Symmetrical’ model – whereby meaningful dialogue, that builds a mutual understanding between an organisation and its ‘public’, is created.

So how do we do this? By taking the journalists on the journey with us. Researching this relationship between the journalist and the press officer, Professor Jean Charron said, ‘public relations practitioners cannot succeed in their job unless they collaborate with the press’ and ‘the incentives to cooperate follow from the interdependence of the two groups.’ If we build better relationships with journalists by knowing the stories they are interested in, asking how we can help them cover a story, personalising emails, providing press event opportunities and ‘exclusive’ stories – the earned endorsement will follow. Picking up the phone is also important to building those relationships and, perhaps more importantly, being reachable on the phone.

To Conclude

It’s important to note that stories still need to be factual. That’s why the press release is still considered to be the most trusted source of information journalists build their stories upon. I believe we can remain factual, and get our narrative told, by finding those human-interest hooks – essentially thinking like a journalist. Paul Smith wrote: ‘Stories are contagious. They can spread like wildfire without any additional effort on the part of the storyteller.’ Imagine how much quicker they could spread if we continue to adapt them to the ever-changing landscape of online media and consider how our multi-media adaptable stories can help journalists do their job.

I guess the take-away here is that we should all be thinking about selling our comms content like a sort of ‘package deal’ – a buy one (the story) get one free (the digital content) and delivering it all with a smile (the relationship).