The hard easy job paradox

I’ve seen public relations degrees recruit well, but struggle to shake off a reputation for being lightweight and non-essential. In short for being easy.

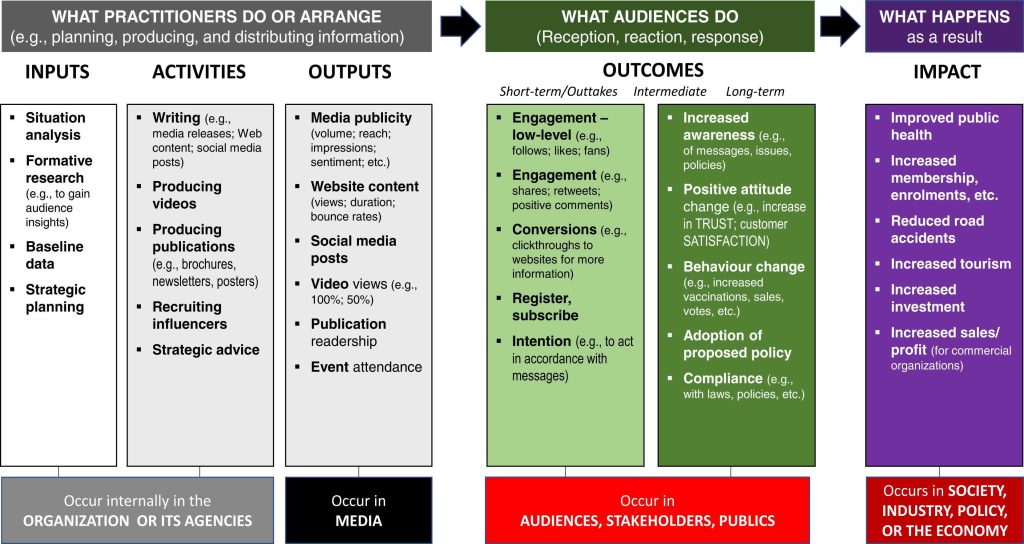

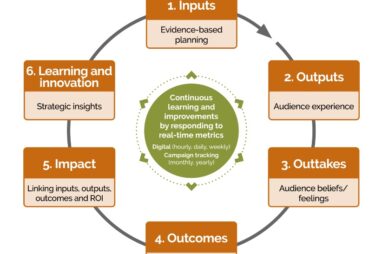

The problem of doing an apparently easy job that just happens to be hard is that we’re forever on the defensive: having to explain why our message did not land; why click or open rates appear so disappointing; and ultimately having to justify the value of the role.