Why reading is essential

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

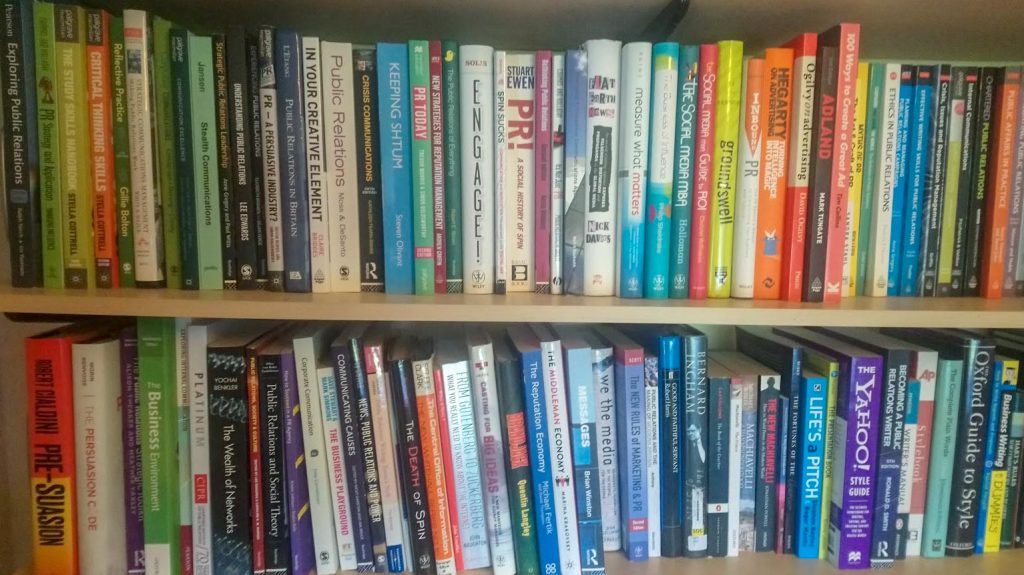

Books about public relations have been a talking point this week – a choice of words I never expected to use.

There was the issue raised by PR Week of the male domination of the PRCA’s reading list for its Diploma qualification. (I’ve also been wondering who’ll be first to note the male domination in the PRCA’s new series of practice guides. Five titles have been published or announced – and all the authors to date are men.)

This issue was picked up by Ella Minty who is running a Twitter poll to ask if we choose books based on the author’s gender. At the time I looked over 200 had voted with 99% claiming they did not. Obviously.

Why do you read a book? Because it’s:

— Ella Minty (@EllaMinty) March 11, 2019

Meanwhile, PR Moment editor Daney Parker has been inviting comments on whether practitioners read books about public relations – specifically, books covering theory.

Her piece has not yet been published, though some have posted their comments to LinkedIn.

There are two questions here: the question of gender and the question of a perceived divide between theory and practice.

I want to explore the role of books in transmitting ideas and theories in a professional field.

To set this in context, I know as a university lecturer how hard it can be to encourage students to read. Libraries have been rebranded as ‘learning centres’, as if to distance themselves from the fusty association with printed books.

Even academics at the leading research universities acknowledge that while students might still be assumed to be ‘studying’ for a degree, they can no longer be said to be ‘reading’ a subject. Setting high expectations around reading can be career limiting for academics in a world of ‘student satisfaction’. The consumerisation of higher education means following the laws of marketing: give the customer what they want!

But that’s not all. It’s also a question of channels and media. We’re used to reading on our devices – and audio books have become a surprise phenomenon.

Let’s keep an open mind about these questions. On several recent occasions I’ve continued ‘reading’ a book I’d already started by continuing with the audio book on a long car journey. If it’s well read (and that means usually by an actor rather than the author), then there are upsides to the audio book over the printed version.

I’m guilty of reading too many blogs. I live with what someone close to me calls ‘Twitter brain’. So it’s not just my students who suffer from a short attention span. We all do. It’s always been hard to distinguish between the urgent and the important.

But the case for books is, I think, similar to the case for news commentary.

There’s so much noise and confusion that we need commentators to make sense of all the ‘sound and fury’. That’s why I subscribe to The Economist, a news weekly. (And I’m completely neutral on whether I prefer the print edition or the online version. I like them both. All right, if I had to choose one, I’d pick the app.)

So, we can limit our reading to blogs, Twitter and other social media and we’d gain a huge amount. But we’d be missing out on perspective.

That’s where books have a place. Because they can’t attempt to be up to date (there’s always a time lag between researching and writing, between writing and publication) – they have to replace urgency with authority. (What is the meaning of ‘author’ if not authority?)

One assumption is that an author (an authority on a subject) should know what they’re writing about. Another is that they should know what others have written on the subject.

This process is embedded in the academic method (where it’s known at the literature review). Sadly, it’s too often lacking from practitioner books. I understand that practitioners are busy, and that having a comprehensive view of what’s gone before is time-consuming. But this isn’t an excuse: if someone isn’t an authority, why are they posing as an author? Surely it’s an argument for co-authorship where an academic contributes the theoretical perspective and the practitioner the real-world experience.

This combination is popular in the US (take for example John Doorley and Helio Fred Garcia’s Reputation Management) but uncommon in the UK. Practitioner Tony Langham solved the riddle in his own book called Reputation Management by inviting contributions from scholars and practitioners. The usual approach is for academics to edit a book and include contributions from scholars and practitioners. We saw this with Nicky Garsten and Ian Bruce‘s Communicating Causes.

So far, I’ve argued for a ‘best of both worlds’ combination of scholarly and practitioner insights. But what might practitioners gain from purely academic texts?

I think the answer depends on your view about professionalisation of the field.

If you view public relations as a practice that’s best learnt ‘on the job’ (ie it’s a trade or craft), then you can ignore the academic contribution as irrelevant to you.

But if you view public relations as a profession (or a would-be profession), then you need to seek out the body of knowledge. No doctor or lawyer could practice without awareness of the body of knowledge in their field. It would be negligent – dangerous even.

The body of knowledge is largely created and curated by scholars. So it’s self-defeating for practitioners to proudly proclaim their ignorance of the academic contribution to the field. That was the gist of the chapter I contributed to the CIPR’s Platinum book last year.

Not that I’m looking to apportion blame for a failure of communication on one side only. I can also accept that too little academic work crosses the divide, largely because the demands of peer approval mean that academics write for fellow academics and are incentivised to think narrowly rather than broadly about questions.

Our purpose at PR Place is to bridge the apparent divide between scholarship and practice. That’s why we publish book reviews, and are as likely to welcome books by intelligent practitioners as groundbreaking books by scholars.

And as a gift to anyone who’s read this far, here’s a very short list of books by academics and educators that speak as much to practitioners as to fellow scholars. View these as essential books, and keep an eye on our book reviews for more suggestions.

I shouldn’t count, but I don’t think you could fault my perfect gender balance. You’re welcome to suggest additions or substitutions to this essential reading list. But it needs to stay short as the truth is that people have many demands on their time, and reading can seem like a luxury.

Public relations: an essential reading list

Note: There are no affiliate connections, the link to Amazon UK is purely to be helpful. I have worked with most of those named, but this is my independent list and every academic and educator will feel they could do better. Thank you Routledge for being the dominant publisher.

Introductory

Ron Smith (2013) Public Relations – the basics, Routledge

This is a more sophisticated book than the title suggests, but US author Ron Smith’s skill is to simplify and make scholarly concepts accessible.

Intermediate

Trevor Morris and Simon Goldsworthy (2016) PR Today: The Authoritative Guide to Public Relations (second edition), Palgrave

An opinionated and no-nonsense book admired much more by students and practitioners than by academics.

Alison Theaker and Heather Yaxley (2018) The Public Relations Strategic Toolkit: An essential guide to public relations practice (second edition), Routledge

This book provides a broad overview of theory and practice and it has a valuable section on public relations planning.

Advanced

Anne Gregory and Paul Willis (2013) Strategic Public Relations Leadership, Routledge

This is a groundbreaking book in its focus on leadership rather than management. It also adopts endnotes rather than academic referencing, making it a shorter and easier read.

Johanna Fawkes (2014) Public Relations Ethics and Professionalism: The shadow of excellence, Routledge

This is the grown-up book on this subject. The reference to ‘excellence’ is that the book challenges the so-called dominant paradigm in public relations scholarship.