Consent is key to relationships

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

With a few exceptions, all relationships are based on consent.

No, this is not another post about #metoo or #timesup – though the principles are the same.

In public relations, we need to develop relationships based on consent, not conquest.

The Cambridge Analytica/Facebook episode provides a warning about the misuse of data, and the distinction between agreeing to terms and conditions and providing consent. The presumption is that consent is informed, and that it can be retracted if trust is broken.

The imminent arrival of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) should heighten our sense of the importance of consent.

Here’s a traditional example of how consent works in public relations practice.

The media ring-round is a persistent feature of some public relations consultancy work. The idea is that having sent out a press release, junior members of the team are tasked with phoning a list of journalists to ask ‘did you see our press release?’

Client service requires an ability to gauge the likely response to a news announcement, so the media ring-round is driven by the needs of client servicing, not by the needs of the media.

From a time-pressed journalist’s point of view, the press release was not requested. Nor was the follow-up call, offering nothing of value.

Some practitioners get around this by using the follow-up call to offer something new (photographs, an interview, extra information).

The best avoid phoning once the press release has been issued. They phone beforehand.

In this case, the call is used to outline the story and to ask if the journalist would like to see it early. (There’s an opportunity at this point to discuss exclusivity and embargo terms).

Given that offer, most journalists will give their consent – for fear of missing out on the story.

Now that you have consent to send through the news, you also have presumed consent to follow it up to check if the journalist has received it and if they have everything they need to prepare their report.

Public relations practitioners used to have a poor reputation for sending out unsolicited spam. The ease of email and the reluctance to pick up the phone have only made this worse.

Yet there are even worse examples from an industry that seeks a conquest rather than a relationship. This does not excuse bad practice in public relations, but it puts it in perspective.

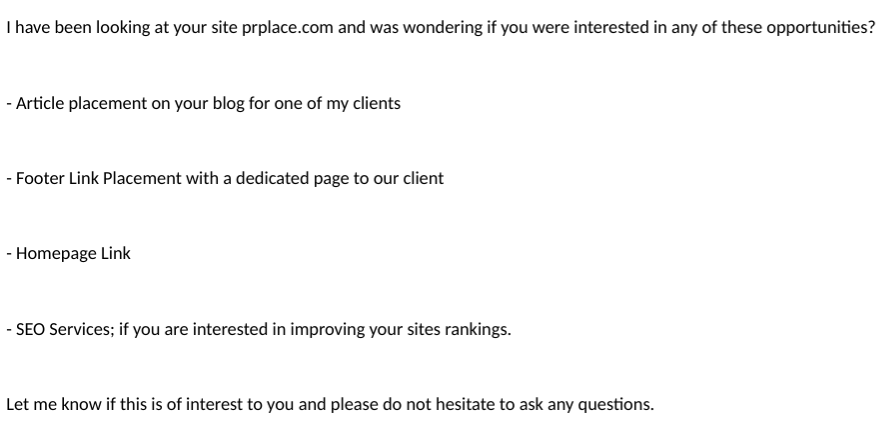

Here’s the approach of some in the digital search industry. There’s no attempt to hide that the approach is driven by the needs of their client. There’s no attempt to answer ‘what’s in it for me?’.

It’s not coercive and it’s easily ignored (I never reply, because that gives consent for a further dialogue where’s there’s nothing to say) though it is spammy.

The tools are there for easy dissemination of one-way promotional messages. Yet this approach can be counter-productive. Instead, we need to ask ourselves some different questions:

- What value am I offering to others?

- What am I contributing to the conversation?

- What happens if I gain a reputation for always putting my own needs first?

There’s nothing new in this. It was foretold in The Cluetrain Manifesto in 1999, and is known as ‘the golden rule’ in religion (‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you’).

If we’re in public relations and we see ourselves as expert communicators, then we need to review our approaches to relationship building.

So what are the exceptions to the principles that all relationships are based on consent?

Is it the citizens of nations who may have once given their consent to be governed in an election, but years later find themselves ruled over by a dictator for life? The state certainly has tools for coercion – but there are always limits. We saw how quickly communism collapsed in eastern Europe in 1989 and while the Arab Spring did not herald summer, it shows that citizen protest can be a potent force.

Prisoners are one exception, society determining through police, courts and prison service that certain people should be kept under control for a period of time.

And family relationships are the other. We do not choose our parents or siblings and cannot divorce them. These are relationships for life. All others need constant work and continuous adaptation.