Developing an influential Public Affairs strategy

About the author

Martin Flegg Chart.PR FCIPR is a PR professional specialising in internal communication. He is also a guest tutor and assessor for PR Academy on CIPR qualification courses.

This case study by Antony Bennett was developed for a CIPR Specialist Diploma in Public Affairs assignment while studying with PR Academy. It has been edited for publication by Martin Flegg.

Public affairs involves an organisation’s relationships with political stakeholders. Public affairs practitioners explain and expose organisational policies and views on public policy issues, assisting policy makers and legislators in creating better policy and legislation. They provide factual information and lobby on issues which could have potential or actual impact on an organisation’s ability to operate successfully.

This case study outlines an approach to developing a public affairs strategy, using the topic of the reform of Insurance Premium Tax (IPT) as subject matter, to demonstrate appropriate situational research methodologies and stakeholder analysis.

It explains the need and potential for strategic engagement with Members of Parliament (MPs) to reform IPT as an issue of public concern, and sets out a possible influential communications approach to build urgency and consensus to reduce the rate of IPT back to pre-2015 levels.

Background

Insurance Premium Tax is a tax on general insurance premiums, including car insurance, home insurance and health insurance. Since its introduction there has been a significant increase in the standard rate of IPT from 2.5% to 12%.

The insurance industry is concerned that if insurance becomes increasingly expensive, consumers may choose not to purchase its products. The Association of British Insurers (ABI) has highlighted that the number of people covered by personal health insurance dropped by nearly 10% between 2015 and 2019, coinciding with the period when the standard rate of IPT doubled.

The Social Market Foundation’s (SMF) report ‘The Impact of Insurance Premium Tax on UK Households’ (2020) described IPT as a regressive tax. It found that the lowest 10% of households, by disposable income, spent 4.1% of their post–tax income on insurance, compared to 1.6% for the highest income 10% of households.

Situational Research and Analysis

To better understand the approach and objectives of the required strategic engagement approach, research was undertaken to answer the following questions:

- Why was IPT introduced?

- What revenue does IPT raise?

- What impact does IPT have on consumers?

- What Parliamentary discourse has there been on IPT since 2010?

- What would an appropriate rate of IPT be?

To address these research questions, analysis of industry bodies, Think Tanks, Government reports and Hansard was undertaken, together with identification of key stakeholders and relevant political and economic contexts.

Why was IPT introduced?

IPT was introduced to correct for the exemption of insurance from VAT under EU law. Over time, government policy then deviated from correcting for the VAT exemption towards raising revenue.

What revenue does IPT raise?

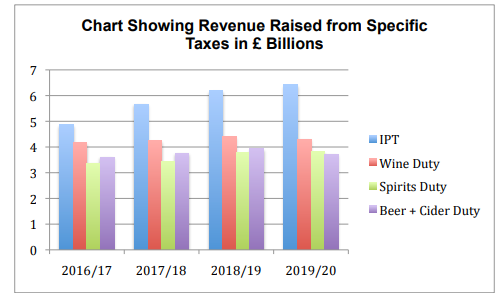

The rate of standard and higher IPT has increased over time, with the standard rate doubling between 2011 and 2017.

During the 2015 General Election many tax rises, including National Insurance, VAT and Income Tax, were ruled out by the Conservative Party. This explained the increase in IPT from 2015, as revenue needed to be raised but fewer taxes could be increased to do so.

In 2015, Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, supported this view stating “the refusal of all political parties to contemplate a rise in the three biggest revenue earners would heighten the risk of stealth taxes shouldering the burden”.

The available statistics show that total IPT receipts in 2020 were £6.347 billion. This was more than double the £3.043 billion raised by IPT in 2015, from which point a steady increase in revenues was seen.

The SMF report (2020) highlighted that standard rate IPT had increased much more rapidly than a number of other taxes, including tobacco and alcohol duties.

The chart below compares the revenue raised by IPT and selected ‘sin taxes’, with IPT raising considerably more.

For a tax on a public good and a behaviour benefitting society, raising more revenue from taxes on insurance, rather than on products deemed to have harmful impacts, could be considered to be an incongruous use of the tax system when considering its function in modifying consumer decisions.

For a tax on a public good and a behaviour benefitting society, raising more revenue from taxes on insurance, rather than on products deemed to have harmful impacts, could be considered to be an incongruous use of the tax system when considering its function in modifying consumer decisions.

IPT’s impact on consumers

In early 2020 the ABI referred to IPT as ‘the mother of all stealth taxes’ and one which penalised people for doing the right thing and saving the state money. They further outlined how IPT penalised drivers for complying with the law and hit those facing the highest premiums the hardest, such as younger drivers. This view was echoed by the SMF who stated in its 2020 report that higher rates of IPT translated into greater costs for households, which they either needed to live with or mitigate through reducing their use of insurance products.

The SMF went on to highlight that IPT impacted on households through its impact on businesses. This is because IPT cannot be claimed back by businesses in the same way that VAT can and costs may then be passed on to the consumer through higher prices.

The Taxpayers’ Alliance outlined that IPT not only made holidays, homes and electrical goods more expensive to insure, but over-taxing insurance meant that there would be too little insurance underwritten.

This part of the research concluded that the impact of IPT on consumers could mean that those on lower incomes could only afford a lower level of insurance than would be preferable, or that they went without insurance altogether. Lower income households could also face underlying reasons why their insurance premiums are higher. This was because of the way in which IPT is applied on the total cost of the premium, exacerbating the issue of lower income households paying proportionately more for insurance. Overall, this makes IPT regressive.

Parliamentary discourse on IPT since 2010

Early day motions

The research looked at Early Day Motions (EDMs) and parliamentary debates. This enabled the identification of supportive MPs, as EDMs are used to put on the record the views of MPs or to draw attention to specific campaigns.

- EDM 741, tabled on 29 November 2016 and signed by 19 MPs, sought to draw attention to the increasing cost the rise in IPT had on families and called on the Government to review its decision.

- EDM 543, tabled on 15 November 2017 and signed by 17 MPs, outlined that IPT had risen more than tax on tobacco since 1994 and penalised people for doing the right thing. The EDM also asked the Government to freeze IPT for the rest of the 2017 Parliament.

The signatories of these EDMs, the majority of which were current MPs at the time of the research, could be viewed as core supporters for reforming IPT.

MPs

A search for the phrase ‘Insurance Premium Tax’ on Hansard revealed that since 1 January 2010 there had been 287 references to IPT.

A number of MPs had raised concerns about increases to IPT and its impact on consumers, particularly those that faced higher premiums already. Their contributions had largely been made during debates on Finance Bills and Budget Resolutions. However, IPT had also been mentioned in other debates due to the relevance of insurance to a range of topics.

This analysis demonstrated a consciousness of IPT and its impact on the cost of insurance, albeit amongst a relatively small proportion of MPs.

Statements by Government Ministers

In a Finance Bill debate on 27 June 2016 Harriett Baldwin MP, then Economic Secretary to the Treasury, stated “IPT is a tax on insurers, so it is for insurers to decide whether to adjust their prices in response to this rate change”. She then went on to state “we do need to raise tax revenues”.

In the Finance Bill debate on 25 April 2017, then Financial Secretary to the Treasury Jane Ellison MP stated “By increasing insurance premium tax, we will ensure that we can maintain the balance between that investment and controlling the deficit”. She also highlighted that “Insurance premium tax is a tax on insurers, not consumers. It will be insurance companies’ choice whether to pass on the 2% rate increase … the impact would be modest, costing households less than 35p a week on average”.

This demonstrated a consistent HM Treasury position on the passing on of costs of IPT to consumers and its revenue-raising role.

In view of this, it was concluded that it would take pressure from MPs on the Government’s backbenches to bring substantive reform of IPT, given the financial situation of the UK as a result of the pandemic, and this would need to be factored into any communications approach.

Appropriate rate of IPT

The 2017 briefing note from The Taxpayers’ Alliance outlined that those sectors with high pay-out ratios are disproportionately taxed and to be genuinely equivalent to VAT at 20%, IPT for property insurance would need to be 8%, whereas for motor insurance it would need to be 3%.

This view was supported by Paul Johnson from the Institute for Fiscal Studies who stated in a 2016 newspaper article that “the ‘correct’ tax on insurance for households would be 20 per cent of the difference between premiums and pay-outs. Since IPT is levied on premiums alone, that would roughly equate to a low single-digit tax rate. So, a 12 per cent tax on premiums is much higher than the appropriate rate on households”.

Key Findings

The evidence gathered in the situational research and its analysis identified the following key findings:

- IPT was introduced to broaden the tax base, raise revenue and correct the under taxation of insurance, covering most general insurance, because extending the coverage of VAT to insurance was contrary to European Law.

- IPT deviated away from its purpose to correct the exemption of insurance from VAT and became a ‘stealth’ revenue raiser.

- For IPT to be equivalent to VAT, different sectors would require different rates due to varying pay-out ratios.

- Revenue received by the Government from IPT more than doubled from 2014/15 onwards, raising more than a number of ‘sin taxes’.

- IPT is regressive as it is applied as a proportion of the total premium, meaning those on lower incomes pay a higher percentage of their income than those on higher incomes. For this reason, it also impacts those facing higher premiums more.

- There were two EDMs in 2016 and 2017 that had a number of signatories, but the wider MP discourse on IPT has been limited.

- HMT’s position had been consistent since 2011. That IPT is a tax on insurers not consumers, and had a revenue-raising role, and it was up to insurers to decide whether or not IPT was passed on to consumers.

These findings were important as they summarised the analysis of where IPT policy had come from and how it was working and could therefore inform recommendations. As Thomson and John (2007) state, “without the knowledge of government thinking, how it has changed over time and what the current position is, the lobbying will not be successful”.

Stakeholder analysis

Stakeholders can be defined as being a person, group of people or organisation that is affected by what a project is doing, or can affect it. Using this approach, the following stakeholders were identified:

- MPs

- Think Tanks

- Industry Bodies

- Consumers

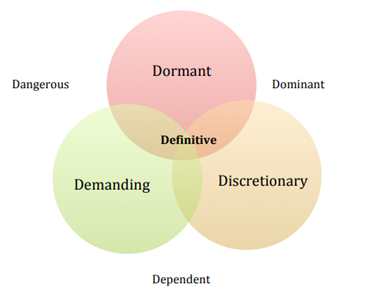

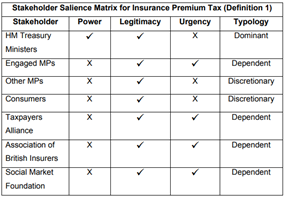

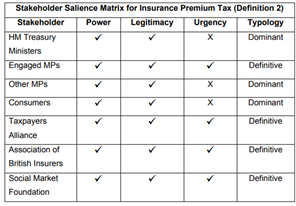

Mitchell’s salience theory was used to assess and evaluate the power, legitimacy and urgency held by these stakeholders. Two definitions of ‘power’ were used, one based on the ability to get the outcome desired and one focusing on the power to influence and agenda set.

This helped to identify and categorise stakeholders as definitive, dependent, discretionary, demanding, dangerous, dormant or dominant.

Power to get the desired outcome

Power to get the desired outcome

This first definition takes the position, that those with power have the ability to get the outcome they desire.

This stakeholder analysis demonstrated that HMT Ministers, including the Prime Minister as First Lord of the Treasury, should be considered as dominant stakeholders as they have power over tax policy and the legitimacy that comes with their office. HMT has the final say over Budgets, Spending Reviews and general tax policy and sets the fiscal agenda. The Government also controls the Business of the House. However, the situational research had also shown a lack of urgency on their part to reform IPT.

MPs who had actively campaigned on IPT could be regarded as dependent stakeholders with the legitimacy that comes with their position and urgency to change the policy, but having a lack of the power to do so unless there was a large-scale rebellion against the Government. Remaining MPs were viewed as discretionary stakeholders as they had legitimacy, but lacked urgency to reform IPT or the power to change the law directly.

Consumers were viewed as discretionary as they had legitimacy for reform but there was a lack of evidence to show their urgency. Their power was also limited outside of election cycles unless they were actively campaigning.

Think Tanks and industry bodies were classified as dependent as they lacked the power to get the outcome they desired.

Power to set the agenda

Taking an alternative view of ‘power’ in which, it encompasses the ability to set the agenda, all MPs were viewed as having the power to dictate parliamentary discourse and the ability to vote on legislation such as Finance Bills and Budgets. Under this view MPs could all be viewed as definitive.

Consumers, under this definition, also had power in as much as they were able to influence MPs as constituents and could be dominant stakeholders. In order for them to become definitive stakeholders, further education on IPT would be required to build urgency and to highlight their influence on political actors.

Likewise, Think Tanks and industry bodies would also have agenda setting power and could therefore be viewed as definitive stakeholders.

This stakeholder analysis demonstrated that all MPs should be viewed as active stakeholders, separated into distinct groups to better inform the communication-based actions to take. For example, those who had previously signed EDMs on IPT were more likely to be receptive to requests for meetings on the issue or the asking of written and oral parliamentary questions. Other MPs however, would need to be convinced of the problems with IPT before they could see it as an issue that needed tackling.

Recommendations, aims and approach

Two key recommendations were derived from the findings of the situational research and analysis to help instigate and drive the reform of IPT:

- Businesses in the insurance sector should engage directly with MPs to build support for reforming IPT back to 2011 levels by the end of the current Parliament.

- Businesses in the insurance sector should build an education program for consumers on IPT to build support among the public for reducing the rate.

Persuasion theory was used to inform a suitable communication and engagement strategy to address the two recommendations. This approach recognised that MPs have free choice over how they vote and any action to influence this should recognise their perception and understanding of IPT and be done using messaging that resonated with current political and economic contexts.

Observing and complying with ethical codes of practice, such as CIPR’s Code of Conduct, would ensure the campaign would be conducted in a manner that was transparent, factual and served the public interest.

Aims

To address the first recommendation businesses in the insurance sector should prioritise building knowledge among MPs of the negative impacts of IPT, particularly its regressive nature and the impact and cost to society from under-insurance, to build consensus for reform. MPs’ focus should be on the benefits reform will have for their constituents.

The second recommendation should inform consumers of IPT’s impact on particular groups, such as young drivers and those who face higher premiums, and lead to increased engagement from consumers with MPs on the need to reform IPT.

What should reform of IPT look like

Businesses in the insurance sector should call for standard rate IPT to be reduced at Budgets for the remainder of this current Parliament with an objective to progressively reduce the lower rate from 12% back to the 2011 level of 6% in line with the IFS’ suggestion by the 2023 Budget. Higher rate IPT should be reduced back to 17.5% at the 2023 Budget.

Engagement tactics

Produce a series of briefing papers for MPs, starting with HMT Ministers, members of the Treasury Select Committee and MPs who have previously signed EDMs on IPT. Engagement would then move to all MPs, focusing on face-to-face meetings. Supportive MPs should be asked to hold Adjournment Debates, 10 Minute Rule Motions, Westminster Hall Debates and EDMs to build awareness among MPs and to create momentum in favour of reforming IPT, to put political pressure on HMT ahead of Budgets.

Work with industry bodies, such as the ABI and BIBA, Think Tanks, such as the SMF and Taxpayers’ Alliance, and the IFS and business bodies such as the Institute of Directors, Confederation of British Industry and Federation of Small Businesses, to create an educational campaign for consumers on the impacts of IPT.

Antony Bennett – What I learnt from completing my assignment

“I’ve been working within the broader public affairs environment for a while now, and for my next career move I’m looking to transition into a pure public affairs role. So, my main reason for completing my Public Affairs Diploma course and the assignment was to take all the transferable skills I’ve already gained and underpin them with a qualification in public affairs to help me achieve that.

From my experience in my current role, I was already very familiar with some aspects of public affairs practice such as stakeholder analysis, but the course taught me to look at this in a very different way.

In my assignment, I used the Salience Model of Stakeholders, looking at their power from two different perspectives. What I’d never really thought about before, in my work, was the salience of stakeholders in terms of their power and how this manifests itself. So, for example what type of stakeholder are they, dominant, discretionary etc. and why is that the case? Identifying this is crucial to understanding how to effectively engage with each type of stakeholder on a policy issue and develop an influential public affairs campaign to achieve that. Thinking about stakeholders in this way has been really useful in my current role, and will also be in the future, when I hopefully make the transition into a new public affairs role.

On the theoretical side of the course, insider/outsider theory was also really interesting, and quite relevant to my current work. This tied into stakeholder salience really well, because your position as an insider or outsider largely determines the power you have on an issue. This made me think about what constitutes an insider vs. an outsider. For example, can an organisation be seen as both at the same time, and how does this influence the choice of campaigning techniques to deliver information to identified stakeholder groups.

Underpinning my transferable skills with a qualification has been incredibly valuable and my experience of completing the course has been very positive. In particular, having my tutor as a resource who has worked in the industry, and being able to listen to her experience and that of others on the course who are already working in public affairs has been both interesting and informative. It has strengthened my resolve to make the transition into a new public affairs role, and confirmed that it is the work that I really want to do. “

References

Ronald Mitchell and Bradley Agle. (1997). Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Vol.22. No. 4. Academy Management Review.

Nigel M. de Bussy and Lorissa Kelly. (2010). Stakeholders, politics and power. Towards an understanding of stakeholder identification and salience in government. Journal of Communication Management. Vol. 14. No.4. p.289 –305. P.300

Richard Perloff. (2017). The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. p.22