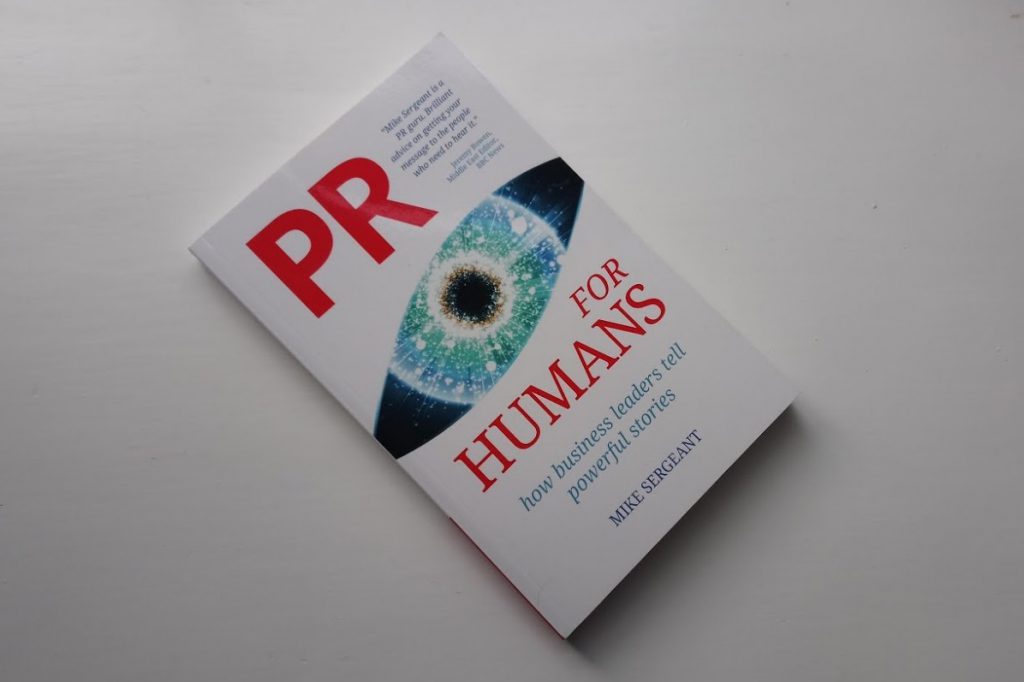

Review: PR for Humans

‘I’ve come to believe that the coaching mindset is critical in PR, both for comms advisers and business leaders. The adviser who can carefully ask clients the right questions to reveal the real goals, challenges, obstacles and opportunities will be much more effective than the consultant who marches in the room and starts telling people what to do.’

‘The roots are where you have come from (as an individual and as a business) and the things you care about and believe in… Next is the trunk. This is your main, strong, powerful story… The branches are the different angles and opinions you may use in media interviews or conference speeches… The leaves are the show – the words, the images, the soundbites.’

‘Podcasts are becoming increasingly important for business communication because they allow companies to reach and curate niche audiences of super-fans and influencers. Even if the show only has 100 listeners, that’s the equivalent of doing an event in front of 100 people every week. And it’s a lot cheaper and easier to produce.’