Review: Rethinking Public Relations

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

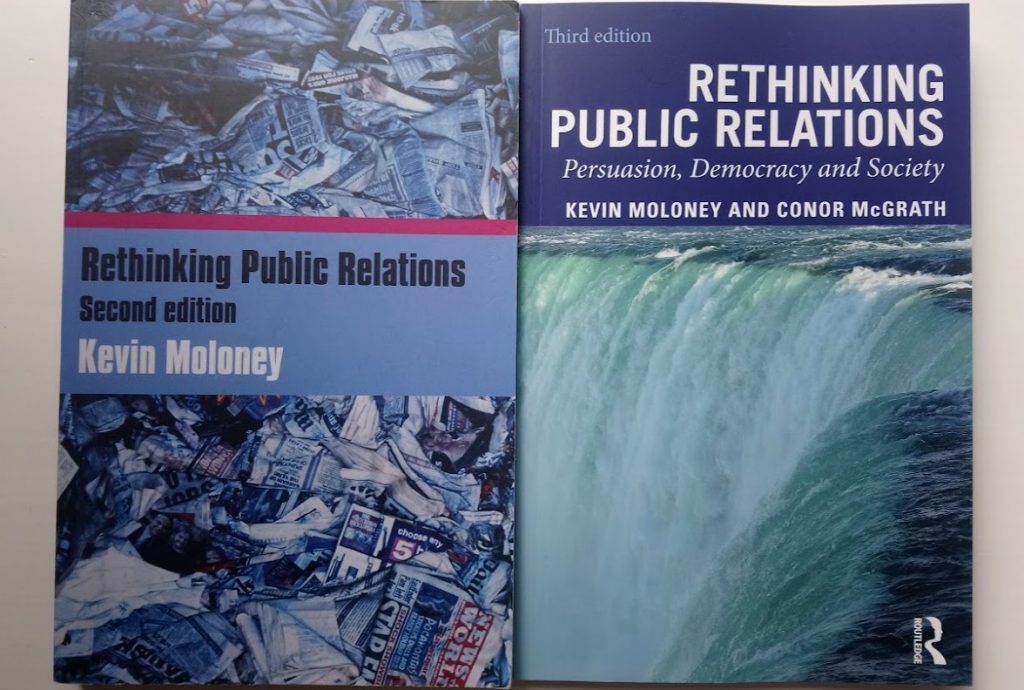

Rethinking Public Relations: Persuasion, Democracy and Society

By Kevin Moloney and Conor McGrath

Routledge, 194 pages, 2020

Public relations is weak propaganda; it is persuasive communication for competitive advantage.

The connection between propaganda and public relations is the central debate in the field’s academic literature. There’s a famous argument propounded by James Grunig that the two are distinctive, separated by history, by intent and by practice. But if so, where does this leave persuasion? Grunig went so far as to suggest (in a book chapter co-authored with British scholar Jon White) that persuasion is inherently unethical.

Kevin Moloney takes a different view. It was brilliantly summarised in the subtitle to the last (2006) edition of Rethinking Public Relations: PR Propaganda and Democracy. Look again: there’s no comma between PR and propaganda. They’re the same thing – though propaganda need not necessarily be bad.

So to this new, third edition of Rethinking Public Relations, a collaboration between Moloney and Conor McGrath. Both authors have a practitioner background and research interest in public affairs and lobbying. Like other critical scholars, they are keen to explore the concept of power and to assess the effects of public relations on society and the public sphere. Where they differ from some other critical scholars is in their belief that it’s possible to be both critical of and useful to public relations.

Why, they ask, is public relations so discredited when it is so widely practised?

It is futile to lament the presence of PR, because public relations is expressive of foundational principles of liberal democracy in its representative variety – its pluralism and promotional culture.

They credit James Grunig for providing an intellectual framework for public relations. ‘He drew an intellectual route map that in its stages distanced PR from propaganda, and made public relations intellectually respectable, decently practisable, and legitimately teachable. The intellectual task now, however, is to scrutinise public relations through somewhat less rose-tinted glasses, to consider its profound impact upon our democracy and society.’

In 150 densely-argued pages, the authors skewer the dominant public relations academic paradigm and also the fashionable argument that public relations is a strategic management function (an argument that is frequently asserted though rarely evidenced). In their view, rather than claiming that public relations leads to social harmony, industry associations should accept that its role is advocacy and counter-advocacy.

PR ought now to reclaim persuasion and influence as its cornerstones (rather than relationships and reputation) because that will more accurately reflect the reality of PR practice.

It’s an important book, though some will find these arguments unpalatable and it’s written for advanced students, is tightly argued and cites numerous academic and practitioner sources.

This edition argues that public relations is and should be persuasive, and persists with Moloney’s previous description of it as ‘weak propaganda’. The new edition supports this argument by including a greater focus on rhetorical approaches, more common in the US than in UK scholarship.

This focus on rhetoric and persuasive advocacy leads to a discussion about ethics and the truth. ‘PR as advocacy is often about communicating a truth, but never the truth – no organisation’s perspective will be the whole possible perspective on an issue.’

If this seems to lend authority to the journalistic taunt about public relations being on the dark side, a more trenchant critique is presented here of practitioners, in Jensen’s words, as ‘hemispheric communicators’ – in that ‘public relations practitioners express messages that speak to only half the landscape. Like the shining moon, they present on the bright side and leave the dark side hidden.’

While truth is discussed, less attention is paid to post-truth. Perhaps the criticism they level at the Habermasian ideal of a benign public sphere could be applied to liberal democracy. Rather than this being a stable end state (and ‘the end of history’), we can now see that the postwar world order is being threatened by rising nationalism and populism with its constant rhetoric of crisis and conflict. It once seemed that public relations sought consensus, but this goal now seems futile.

Public relations and democracy

When the authors turn to a discussion of the effects of public relations on democracy, they explore a useful comparison. ‘We are accustomed to the notion that public relations has a valid role to play in a free market economy… PR is too much a part of our promotional culture for us to easily imagine how society and economy could function without PR. Public relations, though, seems instinctively to fit less easily into our idealised concept of how democratic and pluralistic politics ought to operate.’

Despite the obvious distinction between presentation and policy, the authors argue that because of its importance, public relations is more than just presentational and is ‘an integral part of policymaking.’

Political PR is still widely viewed as spin (the subtitle of the first edition of this book, pubished in 2000, was The Spin and the Substance). ‘Spin is necessary – even inevitable – in politics because so little about politics is neutral or factual – all is contestable, subjective, capable of multiple interpretations.’ Indeed.