Review: Stealth Communications

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

Stealth Communications: The Spectacular Rise of Public Relations

Sue Curry Jansen

2017, Cambridge: Polity

I listen to public relations practitioners and read many of their social media posts. I don’t hear any triumphalism from these sources; indeed, I hear self-critical individuals and a profession that lacks self-confidence and assertiveness.

So it’s interesting to review how the PR business looks to an outsider. There’s good news and bad news in this for practitioners.

Sue Curry Jansen is a professor of media and communication in the US and Stealth Communication is a critical outsider’s perspective on the global public relations business.

She acknowledges that critical perspectives exist within the public relations academic literature, written for fellow scholars, but her book ‘addresses a more general audience: all of us who, we are told, “are in PR now”, but have only a fleeting knowledge of its history, uses and abuses, theories, industry, and pedagogies.’

It is based on a US narrative, arguing that PR and other promotional tools developed first and fastest in America. But she makes many references to the UK and cites many UK academic and practitioner sources.

The narrative is a conventional one: the rise of business interests led to the emergence of an industry that existed to protect and promote those interests. Yet she is critical of PR’s ‘origin myth’ revolving around Ivy Lee and Edward Bernays and the supposed shift from one-way publicity to two-way persuasive communication.

The export of this US model of corporate public relations to the rest of the world accelerated after the end of World War II and after the collapse of communism. Her analysis of the global public relations consultancies and their holding companies is up to date and eye-opening. Citing figures from PR Week and Holmes Report, she notes that ‘in 1990, the top 10 largest firms had revenues of $910 million; by 2000, this had more than doubled to just over $2.5 billion; and by 2014, it had almost doubled again to $4.8 billion.’

The narrative is clear. ‘PR firms often serve as part of neoliberalism’s ideological front guard in efforts to develop new markets and integrate the global marketplace.’

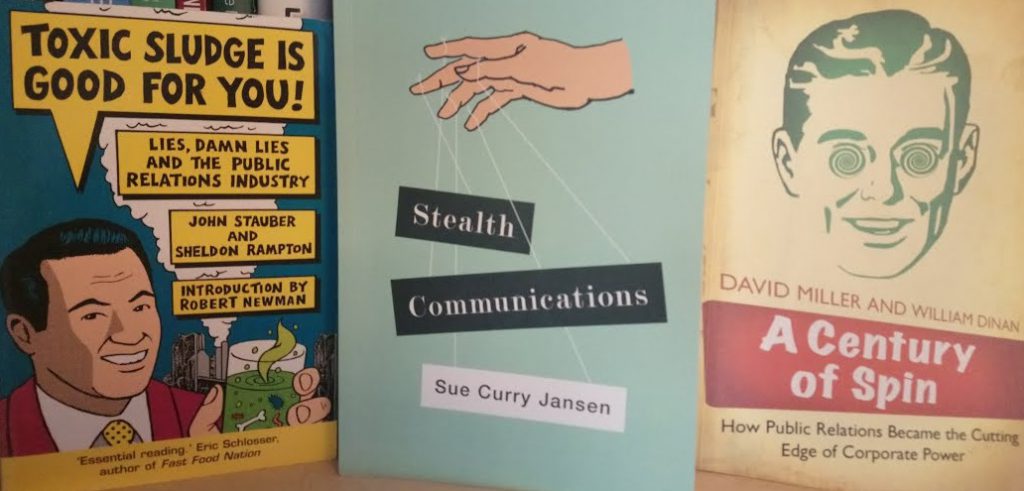

The charge is that public relations has risen alongside private sector business, and that it uses questionable methods such as front groups and ‘astroturfing.’ You may have read about this in Stauber and Rampton’s Toxic Sludge is Good for You!: Lies, Damn Lies and the Public Relations Industry.

The author extends the argument beyond front groups to think tanks. ‘With more than 1,900 US think-tanks and an estimated 6,500 worldwide, even the most vigilant critical media consumer cannot easily distinguish between traditional and partisan think-tanks, know their agendas, or assess credentials of their affiliated experts.’ Good point.

Yet public relations academic texts have tended to ‘present a singular view of PR as an ever-evolving and positive social force.’

I’m not sure how the diversion into nation branding progressed her argument (beyond stating that it involves a flow of money from public to private hands and is at heart propagandistic). But the author is right in her contention that ‘neoliberalism conflates democracy and capitalism; it equates free market economics with political freedom.’

What of civil society organisations? The number of NGOs has increased rapidly in recent decades: ‘Over half of the NGOs in Europe were founded in the 1990s. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, more than 100,000 new nonprofits were created in Eastern Europe between 1988 and 1995.’

Since these organisations claim they serve the public good, their corporate PR critics must only be protecting private interests. But is it so simple? The animal testing laboratory may be acting within the law; animal rights activists physically attacking its workers and investors will be acting illegally. But both sides would claim to be acting for long-term public good.

It’s a question of perspective and interpretation. As is a reading of sources. She frequently cites Morris and Goldsworthy, though few observers would see them as foremost among critics of public relations (nor of neoliberalism). Nor did they express the following sentiment that’s credited to them (I’ve checked the source): ‘PR, especially PR operating in the upper echelons of corporate and government power, is a form of asymmetrical communication that functions as an ideological agent of an elite hegemony.’ That sounds much more like the language of a media studies academic than two British PR practitioners turned lecturers.

Yet the critical outsider analysis of public relations is bracing and welcome. It’s too easy to believe our own myth-making.

‘Visitors from another planet reading American public relations textbooks or visiting some PR company websites could come away from the experience with the impression that PR is planet earth’s center for ethics and global social justice.’

We should continue to be self-critical, just as we need to be alert to the suspicions that we’re uncritical propagandists or unashamed defenders of undemocratic corporate power.

Now back to the day job of articulating and enacting values; of helping to deliver public services efficiently; of explaining that private businesses are large employers and that we as a species depend on their innovations for our survival.