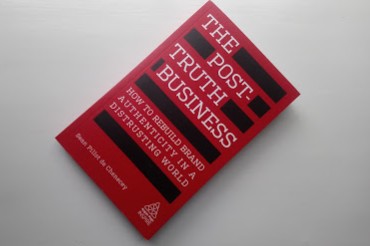

Review: The Post-Truth Business

We’re living in a media landscape where the truth is deliberately manipulated, trust has been catastrophically devalued and organized misinformation is a growth business.

Brands matter hugely. But primarily, it’s the ones that we trust and have an emotional relationship with, and who tell their stories via powerful stories [sic], that will gain and retain our loyalty. It sounds so self-evident, so obvious as to be almost not worth saying, until you consider the omnipresent deluge of brand communication that consistently fails to be ‘motivating, engaging and relevant.’

Brands that are genuine, have integrity, talk in honest terms, play a role in society that provides their consumers [sic], respect the culture within which they operate and demonstrate commitment via purpose-led branding to show that they’re essentially ‘on our side’ are the ones that will continue to grow – because if you’re not authentic then you’re not genuine. In a post-truth world, linking with culture must be about adding value and being authentic.