Are reputational experts failing at protecting their own reputation?

Why PR needs good PRPs

About the author

Holly McLennan MCIPR, Accredited PR Practitoiner, is Communications Manager at Food Standards Scotland. She prepared this article for a CIPR Professional PR Diploma assignment.

The Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) states public relations practitioners (PRPs) are experts at looking after reputation – aiming to earn understanding, support, influence opinion and behaviour. Yet the third biggest challenge practitioners face, according to CIPR’s ‘State of Profession 2019’, is public relations (PR) ‘not being seen as a professional discipline’ – up from fifth place last year.

What we do, say, and what others say about us results in our overall reputation – it’s elementary PR.

We effectively look after reputation for others, but what about our own?

Disclaimer: as a practitioner, I’ve not always been the best at looking after PR’s reputation. Allowing the discipline to be misunderstood by family / friends is one thing, but devaluing it in business is professional and organisational suicide.

Perhaps there was more of an excuse when I was an Account Executive, working for an energy sector-specialising PR agency – distracted from the bigger picture by a long, tactical to-do list. Press release – tick; social media posts – tick; media sell-in – tick. Technically, I wasn’t misguided; copywriting, editing, social media and media relations are the most valued skills recruiters look for in junior PRPs.

Then the oil price plummeted. Companies made significant changes in order to survive. I lost clients who considered the support a nice ‘cherry on top’, but not an “integral part of their institute”, put by Sir David Nicholson, former NHS Chief Executive (CE). Alas, many tactical personnel within the agency were let go.

It’s not all doom and gloom. More than half of PR agencies are growing and in-house departments are more likely to have grown than reduced in size. In Britain, organisations will annually spend billions on PR.

However, we need to get to the bottom of why PRPs’ views on their skills and capabilities, as well as what they deliver, appears to be falling short of PR’s strategic purpose.

The PR Skills Gap

The reality is that even the most senior PRPs are heavily engaged in tactical delivery.

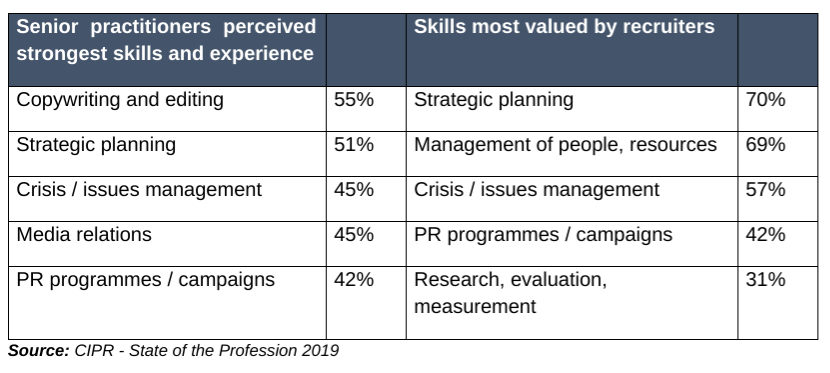

The CIPR’s ‘State of Profession 2019’ highlights 50% of senior PRPs (Managers, Department Heads, Managing Directors and Partners) rank copywriting and editing as one of the most commonly undertaken activities in their job. Less than half have strategic planning and crisis / issues management as a commonly undertaken activity. They also think they’re more strongly skilled at copywriting and editing than strategic planning.

But what do recruiters most value in senior practitioners?

The statistical differences are significant:

Strategic planning, management of people, resources, and crisis / issues management are most valued by recruiters, and nearly a third value research, evaluation, measurement (not even in the senior practitioners’ list). Copywriting and editing isn’t in the recruiters’ list, despite being the number one skill perceived by practitioners.

Strategic planning, management of people, resources, and crisis / issues management are most valued by recruiters, and nearly a third value research, evaluation, measurement (not even in the senior practitioners’ list). Copywriting and editing isn’t in the recruiters’ list, despite being the number one skill perceived by practitioners.

There’s a skills gap.

Amanda Fone, CE of f1 Recruitment confirmed this when highlighting current skills gaps in the PR job market are corporate communications and evaluation / measurement, with big bucks available to those with these capabilities!

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple as there’s still much debate over the duties and responsibilities of PRPs. One thing’s certain: we must demonstrate our contribution to overall organisational effectiveness if we’re to gain societal and organisational acceptance.

‘Good’ PRPs

The irony in communicators struggling to articulate communications doesn’t do much for defending our legitimacy.

A contemporary narration is the Global Capability Framework. In 2018, it highlighted PRPs globally have the following capabilities in common:

| Communications |

|

| Organisational |

|

| Professional (expected of any professional) |

|

Source: University of Huddersfield – A Global Capability Framework for the Public Relations and Management Profession 2018

Strategic PR can be appreciated when one considers the levels that it operates and where it sits, between the internal and external communications environments.

Academic models highlight the importance of PR within the context of the complex, modern stakeholder landscape. Unlike other parts of the organisation, such as finance and HR, which have filtered views through their respective corporate services lenses, we have a panoramic view.

Ever wondered why your department has such good working relations with the CEO? We share this unique holistic view. The CEO has to take all factors effecting the organisation into account when making decisions.

With this in mind, it’s worth considering the expectations that today’s CEOs have of senior PR leaders, as listed by Gregory and Willis.

- Detailed knowledge of the business and external environment

- Extensive internal networks and relationships

- Broad, varied PR background

- Credibility with senior managers

- Team player

- Educator and coach

- Individual on top of the issues, and able to advise on them

- Ability to engage in multiple stakeholder relations with a mature and long-term perspective (authentic rather than purely transactional)

- Strong ethical base, along with personal integrity

- Individual who will tell them “how it is” and provide honest feedback from stakeholders

- Good understanding of the brand, and an ability to promote and defend it

- Ability to develop both business and PR strategies

L’Etang states senior PRPs must play a role in making strategic organisational decisions and be a member of the dominant coalition, or have access to this powerful group of organisational leaders.

She’s backed by many writers, such as Black who flags understanding the business strategy, and strategic planning and evaluation as key professional PR skills, which support the effectiveness of organisations.

Despite the focus on the corporate, constitutive function of PR, Gregory states ‘unequivocally’, communication tactics and content are of ultimate importance. They are key ‘enablers’ to the strategic approach.

Indeed, ‘implementer’ is one of the PR leader’s four organisational roles, Gregory and Willis claim; to deliver appropriate communications activities and programmes based on societal, corporate, stakeholder and service-user objectives.

Their theory sets out the strategic contribution of PR through the Four-by-Four Model: the four strategic operational levels at which it operates (societal, corporate, value-chain and function), within the context of the complex, modern stakeholder environment.

Then, four key attributes – ‘the DNA strands’ – of good PR:

- An excellent understanding of the brand

- Leadership

- PR as a core organisational competence

- Excellence in planning, managing and evaluating public relations

Together they improve trust, reinforce legitimacy, and build and defend the reputation of PR.

Grunig’s excellence model suggests the value of PR is based on the quality of relations with stakeholders, and its ability to listen and adapt to their needs through the organisation’s social responsibility in its management decision-making. This is evidenced in movements by PRPs away from reliance on media relations and opening conversations with stakeholder groups.

For example, our team has recently restructured with a new role of senior stakeholder manager, filled by the former press office head.

While valuing stakeholder management seems intangible, Grunig suggests it can be measured through the value in reducing risks, associated costs, and increasing revenue. This is why PR should be integrated within the whole business planning and monitoring process, rather than just promotional / functional activity.

What’s stopping us?

A white flag does need to be waved for PRPs. We’ve been stereotyped in entertainment / media for decades as girlie partygoers who spend our time “fanny-ing about with press releases” – thanks, Daniel (in Bridget Jones)!

Although, as shows such as Sex and The City and Absolutely Fabulous age, it’s become a tired defence that Samantha and Edina are the main reason PR isn’t taken seriously.

While 67% of PRPs are female, males are 10% more likely to be a PR Director / Partner / Managing Partner.

It’s not great, though, when media outlets such as Radio 4’s Media Show suggested PR is all about ‘publicity stunts’ and ‘getting clients’ news out’, making it sound ‘fluffy’ and calling PRPs ‘liars’. Rightly, CIPR President, Emma Leech, was quoted as saying:

“The truth is tens of thousands of PR professionals provide ethical and strategic support to businesses of all sectors. We help build trust in organisations by establishing and improving relationships with key stakeholders – not just journalists.”

Our ‘truth’ could be haunted by our history. PR grew out of propaganda, and communication experts such as Professor Jim Macnamara from University of Technology Sydney suggest it’s going to take “many more decades and strenuous activity by ethical practitioners to live down the past”.

PRPs, like all professionals, are obliged to do what is right. Members of the CIPR are bound to the Code of Conduct, which includes commitment to integrity, fairness and respect.

One way to ensure you’re acting ethically and responsibly is to fully understand the content that you’re dealing with – satisfy yourself that you’re not misleading the public, as expressed by Carden Calder, Managing Director of BlueChip Communication. A pyramid model, such as Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility, can also be helpful for incorporating ethical reflection and evaluation into the structure of an organisation / PR plan.

The importance of ethics is highlighted when considering unethical behaviour.

Amazon and Starbucks made headlines for paying low levels of corporation tax, which has had a knock-on effect to their reputation. In the aftermath, Amazon’s reputation score fell 6% and Starbucks’s dropped 5%, according to a survey by Reputation Institute in 2017.

As an occupation, PR in itself is ethically challenged. As L’Etang suggests, it entails persuasion. Others, like Virender, go as far as calling it ‘amoral’ as the intention is to engineer / manipulate the public.

Using psychology, PRPs craft messages to resonate with target audiences. We’ve studied cognitive processing, and developed models which highlight the two main routes to persuasion. One is deep, detailed thinking and the other is simple information processing. Some decisions – buying a new car – require all of the facts, while others – purchasing some music – might be based on heuristics; believing a song is good because it trended on Twitter.

While the surface of this seems calculating, psychology can be a tool when supporting a societal or organisational good.

Consider managing internal communications following a major restructuring which has resulted in redundancies. Understanding the psychological impact on staff, particularly ‘survivor syndrome’ and behavioural effect, is paramount.

The more committed people feel to the organisation, the more effort they put in, which in turn impacts productivity and organisational success.

Where do we go from here?

The future for PR looks bright, with increasing dependency on the discipline against the backdrop of various environmental pressures, particularly the complex stakeholder landscape.

To be effective, PRPs must make strategic organisational – as well as communication – contributions from business decision-making to implementation and evaluation.

More research into modern PR leadership is needed. Given there’s no simple articulation of the skills and capabilities required, PRPs are in a vulnerable position when asked to clearly demonstrate their need. Perhaps some humour will get us through – “The easy answer is to list what I don’t do!” says Black.

Let’s not forget the historical and immoral cobwebs, which will require strategic talent and a sound ethical approach to brush away.

The good news? PR’s reputational solution is PR itself. So, whether you’re in a junior or senior position, there’s an opportunity to cultivate PR’s potential and cement it firmly on the professional agenda.

References

Surveys/Reports

- Chalkstream. 2019. Chartered Institute of Public Relations, State of the Profession 2019, [accessed 10/10/19]

- University of Huddersfield. 2018. A Global Capability Framework for the Public Relations and Communication Management Profession, [accessed 12/10/19]

Books

- Tench, R and Yeomans, L. 2009. Exploring Public Relations. Essex: Pearson Education Limited

- Gregory, A and Willis, P. 2013. Strategic Public Relations Leadership. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

- L’Etang, J. 2006. Public Relations: Concepts, Practice and Critique. London: Sage

- Black, C. 2014. The PR Professional’s Handbook: Powerful, Practical Communications. London: Kogan Page

- Gregory, A and Waddington, S. 2015. Chartered Public Relations: Lessons from Expert Practitioners. London: Kogan Page

- Watson, T and Noble, P. 2014. Evaluating Public Relations: A Guide to Planning, Research and Measurement. London: Kogan Page

- Perloff, Richard M. 2017. The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the 21st Century. New York: Routledge

Online

- Chartered Institute of Public Relations. 2016. What is PR?, [accessed: 10/10/19]

- Fone, A. 2019. Influence Bridging the PR Skills Gap, [accessed: 12/10/19]

- Cafebabel. 2019. The Five Worst Stereotypes of Female Journalists on Screen, [accessed: 13/10/19]

- Veulio. 2019. PRs react to the portrayal of the industry in Radio 4’s Media Show, [accessed: 6/10/19]

- PR TV. 2009. A question of ethics, [accessed: 07/10/19]

- Chartered Institute of Public Relations. 2016. CIPR Code of Conduct, [accessed: 12/10/19]

- Tutor2u. 2018. Carroll’s CSR Pyramid, [accessed: 13/10/19]

- Champman, B. 2017. Independent Amazon and Starbucks take reputation hit from tax avoidance publicity [accessed: 12/10/19]