Briefing: The PESO Model

About the author

Richard Bailey Hon FCIPR is editor of PR Academy's PR Place Insights. He teaches and assesses undergraduate, postgraduate and professional students.

Note: This article was first published on 16 September 2019 and updated with new information on 3 April 2024.

The PESO Model (Paid-Earned-Shared-Owned), is widely cited, but is it well-understood? This briefing discusses its origins, its purpose and its application in public relations.

PESO is a media channel framework for digital public relations in an age of increasing integration across marketing communications channels and disciplines.

Understanding media for public relations

Public relations is media neutral. In order to communicate and persuade, practitioners can use any appropriate media channel. This might involve interpersonal communication (face to face); it might involve mediated communication through third parties (such as influencers and journalists). In principle, it can include advertising as well as media relations – though in practice the cost of mass media advertising has meant that historically it was considered a separate discipline to public relations. Traditionally PR has focused on free or less expensive – but less certain – forms of media placement known as earned media (‘pray for play’ versus ‘pay for play’ in Fred Hoar’s words).

Scholar and author Ron Smith provides a useful model of pre-digital communication in which he contrasts the numbers reached by a channel against its persuasive effectiveness. Interpersonal communication is the most persuasive form of communication, but you’re constrained in the numbers you can reach. Mass media advertising has the largest reach, but is the least persuasive option.

So, by the end of the twentieth century there was a well understood distinction between paid media (advertising) and earned media (through media relations and other forms of third party endorsement). Advertising and public relations shared much in common, but there was one important distinction: money.

Digital and social media

Yet by the end of the last century, advertising was faced with a problem. The proliferation of media channels meant that it was becoming harder and more expensive to reach mass audiences with persuasive messages. Advertise too little and you couldn’t cut through. Advertise too much, and you risked boring your target audiences. Author Seth Godin expressed the paradox of advertising in 1999: ‘the more it costs, the less it works. The less it works, the more it costs.’

His answer was to promote what he called ‘permission marketing’ over ‘interruption marketing.’

Branding experts Al Ries and Laura Ries made a similar point in their 2002 book The Fall of Advertising and the Rise of PR. Theirs was a narrow rather than a broad argument: in the case of new brands, you need to lead with public relations (which they understood as publicity). Advertising could follow once the brand had been established. It’s a model that has worked well for technology companies from Microsoft to Google.

Something else changed with the rise of Google and the emergence of social media. Media became cheaper again as it shifted from print to online and from publishers to technology platforms. Advertising was now just a click away and did not involve lengthy media buying negotiations or involve the design and creation of artwork.

Yet, having established market leading positions, these tech firms could adjust their algorithms to make organic (ie earned) reach harder to achieve through social media, thus forcing organisations to pay to promote their messages or face declining communication effectiveness.

The distinction between public relations and advertising was fast disappearing.

The importance of prominent search results on Google is well understood (and well served by the search marketing business). Facebook’s large number of users makes it unavoidable in many sectors.

But should you put all your eggs in one basket? Rather than relying solely on sharing and promoting content on platforms such as Facebook/Instagram, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn or TikTok, organisations have learnt the risks of trusting everything to platforms and publishers who can change the rules, or suffer outages (if you’re not paying to use these services, then you’re not a customer but you do become a target).

This explains the other distinction in the PESO model: between shared and owned media (‘the two new kids in town.’)

Shared media (or social media) is when people like, comment on and share your social media posts and digital content. It has been proving an attractive channel given the popularity of social media and is supplementing or even replacing media relations in some contexts. Certainly, some social media influencers have discovered a more lucrative business niche than journalists in the twenty first century.

Owned media includes your own publications, websites, blogs and other media channels that you manage without relying on third party platforms. It may cost you more in up-front charges, but you remain in control and your content is not at the mercy of some other organisation.

Introducing the PESO model

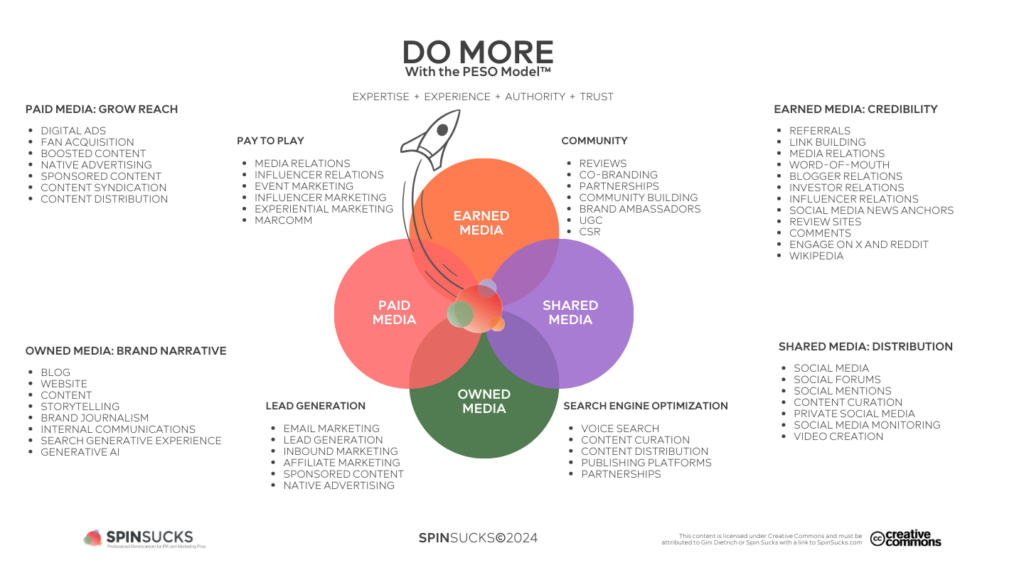

The PESO Model (a media cloverleaf model) is credited to US consultant and author Gini Dietrich. Certainly, she has copyright over the widely-adopted diagram created for the Spin Sucks website and her 2014 book of the same name. This model was updated in 2020 and again in 2024, for the tenth anniversary.

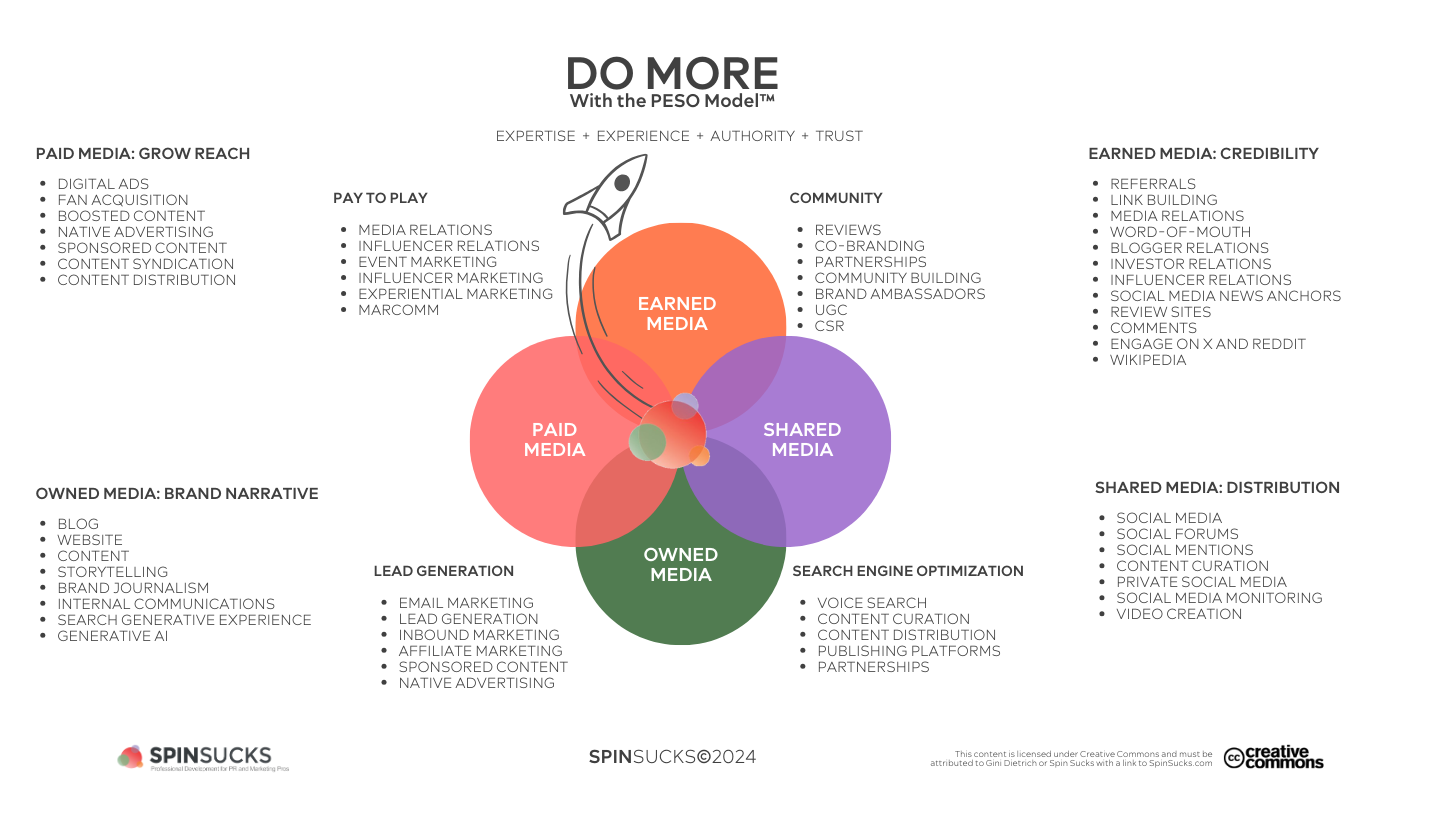

Yet Heather Yaxley reminds me that the acronym PESO had been used by the Ketchum measurement expert Don Bartholomew a few years before this in a 2010 article. (Bartholomew died in 2015). He created a model for paid-earned-shared-owned media, with his focus being on the challenge of research, measurement and evaluation in an integrated age.

Yet Heather Yaxley reminds me that the acronym PESO had been used by the Ketchum measurement expert Don Bartholomew a few years before this in a 2010 article. (Bartholomew died in 2015). He created a model for paid-earned-shared-owned media, with his focus being on the challenge of research, measurement and evaluation in an integrated age.

Yaxley adds: ‘It is also worth pointing out this 2010 McKinsey Quarterly article by David Edelman and Britan Salsburg that includes sold and hijacked media alongside what used to be called POEM (paid, owned and earned media). Both of these concepts still have value even though their execution has changed in the past decade.’

PESO is merely an acronym (a word formed from initial letters). Some have criticised it for appearing to favour paid media by putting this first, but Dietrich has explained that from a communication perspective it should have been OESP except that this would be less memorable and so less easy to brand.

Others have wrongly criticised PESO for encouraging a siloed approach, as if it presents a choice between paid, earned, shared or owned – whereas its intention was to create an integrated model in which all these channels contribute towards the sweet spot of improved reputation. Indeed, the subtitle of her 2014 book Spin Sucks reads: ‘Communication and Reputation Management in the Digital Age’.

Authority is one of the factors contributing to reputation: from a public relations perspective this should be interpreted broadly, but some interpret it more narrowly and measure progress according to a website’s Domain Authority, a rating given by the Moz toolbar.)

For the 2024 update, Dietrich explained her intention to remove detail of channels and focus more on outcomes, presenting a more strategic overview.

‘The biggest shift is in what happens when you use all four media types together, in a cohesive and integrated program: experience, expertise, authority, and trust, or E-E-A-T.’

In the centre of the PESO model cloverleaf used to be reputation: a strong presence in each of the four components would lead to a greater reputation. Now she’s placed E-E-A-T in the centre, reflecting Google’s search guidelines.

Google tells us that to have our content ranked highly we need to demonstrate experience, expertise. authority and trust on that topic. Dietrich tells us that as a result of using the PESO model we’ll achieve recognition for those same outcomes. Isn’t this a circular argument that confuses cause with effect?

Her argument is that in the age of AI it’s so easy to present content that has the appearance of credibility that Google is working harder to de-index soulless content. So content creators have to work harder to demonstrate their humanity and distinctiveness.

‘As AI begins to take over, Google is rushing to remain the leader in search. Recently, they have been on a tear, de-indexing web pages, articles, blog posts, and more all over the web. This is because much of the content on the internet is low-quality, keyword-stuffed, and soulless. All of that content is being moved farrrrr down in search results to make room for content that has a soul.’

Limitations of the PESO model

Yet we should also acknowledge the limitations of PESO. It’s only a media model. Media communication inevitably plays a part in public relations, public affairs and internal communication, but it doesn’t tell the whole picture. What about listening? What about research and analysis? What about creating strategies and plans – and seeking buy-in for these from senior managers, partners and other key players? What about project and client management? What about measurement and evaluation and process improvement?

The PESO Model can help you clarify and resolve media communication problems, but does it help with all public relations problems?

If your problem is retaining staff, say, then the media plays a small part in this challenge.

Remember, not all communication is mediated – sent between a source and a receiver through an intermediary. The most credible communication is often transmitted directly from source to receiver – and not just in conversations and speeches, but also in emails and newsletters and WhatsApp messages (in digital channels certainly, though not necessarily visible to Google or to the wider public).

PESO in practice

The PESO Model may be trademarked by Gini Dietrich, but the words have broader meaning and applicability and we can look to other credible sources to help us navigate the twenty first century media landscape.

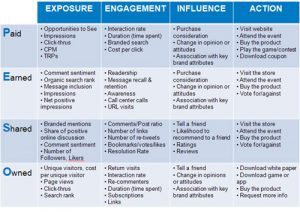

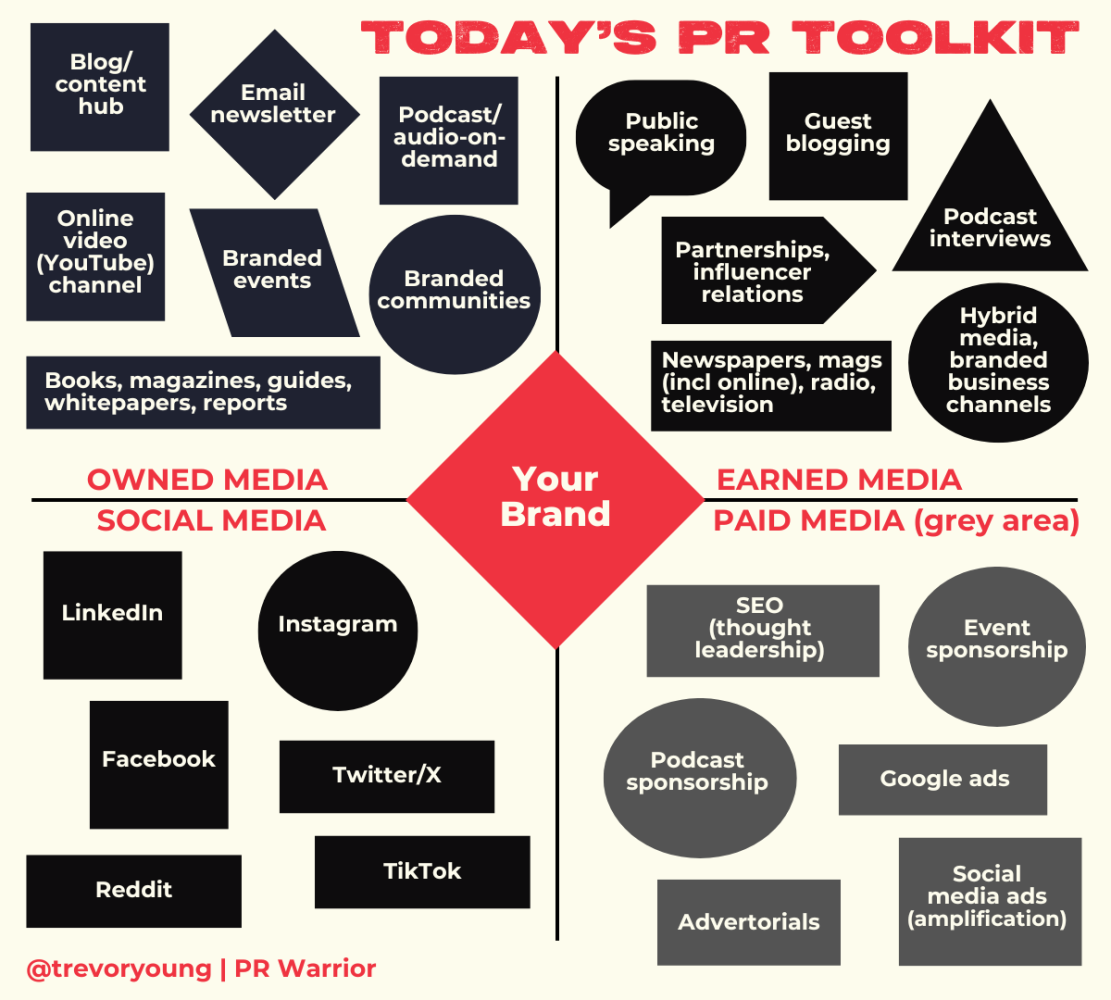

One such source is Australian consultant and blogger Trevor Young. He presents a PR toolkit that uses the same components but in a different sequence.

As Young explains:

‘As you can see from the diagram above, it’s multifaceted: owned media is just as crucial as social media engagement, with earned media being the ‘icing on the cake’, with the ability to turbo-charge the reach and credibility of your business, personal or nonprofit brand.’

He finds the adoption of paid media into public relations practice more problematic than Dietrich.

And he explores media and communication trends, such as thought leadership, podcasts, newsletters, in-person events.

‘Summing up, the world has moved on and traditional PR methods have taken a backseat as businesses and personal brands now have direct access to their audience through various online platforms.’

Final thoughts

To state the obvious, we need to distinguish means from ends. Media is quite literally the means we use rather than the end we seek (that’s usually some combination of awareness, attitude change and behaviour change). The choice of media follows this purpose and is dictated by our knowledge of the groups we are seeking to engage and persuade.

So, you will inevitably be applying some variant of PESO media in your public relations. But this does not give you the whole picture. What’s the purpose of communicating? Who are you trying to persuade? How best to reach them to best effect and how will you know you’ve succeeded?

So we’ve come back full circle to the contribution of PESO to the planning-research-evaluation cycle (described by Mark Weiner as the ‘PR continuum’.)