Holding the NHS to ransom

The cyber-attack that brought the NHS to its knees

About the author

Martin Flegg Chart.PR FCIPR is a PR professional specialising in internal communication. He is also a guest tutor and assessor for PR Academy on CIPR qualification courses.

Kimberley Rushton prepared this case study for her CIPR Specialist Diploma in Crisis Communication assignment while studying with PR Academy. It has been edited for publication by Martin Flegg.

Background

On Friday 12 May 2017, a global cyber-attack known as WannaCry hit more than 200,000 computers across 100 countries. Within the UK, the attack particularly affected the NHS with over 80 hospitals in England impacted either directly by the virus or because they shut down their systems to avoid being infected.

As one of the hospitals impacted, NHS Hospital Trust (the Trust, a pseudonym) swiftly shut down computer systems and then declared a major incident. Since all its computer systems were offline, there was no way to easily access patient information and the Trust’s Crisis Management Team (CMT) decided to cancel all planned, non-urgent appointments and operations, in the interest of patient safety.

NHS England and NHS Digital declared a national major incident when the severity of the cyber-attack became clear. The Trust’s computer systems remained down over the subsequent four days, and more than 3,000 appointments or operations were cancelled whilst other hospitals came back online and communicated that they were back to business as usual.

This case study analyses the communications response to the impact of the cyber-attack on NHS Hospital Trust. A critical review and evaluation using secondary research and academic models informs a number of conclusions and recommendations for action to prepare the Trust for future crisis communication scenarios.

Why should the NHS prepare for future cyber-attacks?

Over the past 20 years, the NHS in the UK has been working towards full digitisation.

National Cyber Security Centre Annual reviews reveal that the cyber threat to the UK is growing and evolving. There were 30 percent more significant incidents in 2021 than there were in 2017 when the WannaCry attack took place. As more and more critical healthcare systems move to digital applications, preparations must be made for the chance that one or more of them will be impacted by a cyber-attack.

The response to the WannaCry attack highlighted how unprepared the NHS was for this type of incident, particularly at a local trust level, which led to the cancellation of more than 19,000 hospital appointments across the UK and cost the NHS as a whole, £92 million.

Research objectives, methodology and analysis

The objectives of the research were:

- To examine the academic models used to inform the recommendations.

- To identify NHS Hospital Trust’s key stakeholders in the event of a crisis.

- To critique NHS Hospital Trust’s communication response to the cyber-attack using academic models.

- To consider any ethical implications of the communication approaches used by the Trust.

A number of analytical methods were used to examine and present information, they included:

- A Bowtie analysis.

- Stakeholder analysis using a matrix approach.

- The application of crisis communications theory.

- Analysis of secondary research.

The data sources used included internal and external reports, regional and national news reports and academic research papers.

Bowtie analysis

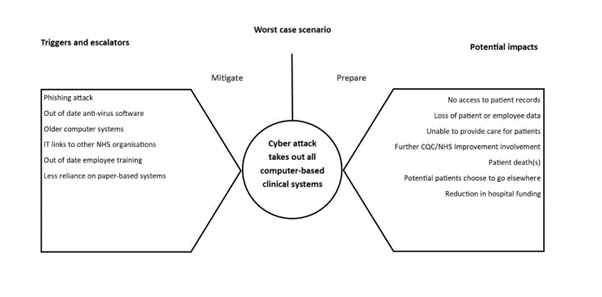

Griffin’s Bowtie analysis was used to map out the known impacts of the WannaCry cyber-attack as a worst-case scenario in order to reflect on the impacts, triggers and escalators.

The analysis demonstrated that in the event of a cyber-attack there were a number of serious potential impacts which cumulatively could lead to a reduction in hospital funding.

Triggers and escalators identified were a mixture of elements both within the Trust’s control and out of it. Those out of the Trust’s control, could not be fully mitigated against but could be noted as a risk.

Stakeholder analysis

The stakeholder matrix was used to identify and classify the Trust’s key stakeholders during the cyber-attack.

Whilst the patients, media and employees were not classified as key players in the matrix, in a crisis scenario they were stakeholders that needed to be kept informed in order for the key players to be appeased. As such, the majority of communications activity focused on that group.

Crisis communications theory

The British Standards Institute for Crisis Management guidance states “Crises challenge organisations, their people, functions and processes unusually, and require dedicated and dynamic management and response.” With that in mind, a consideration of relevant crisis communications theory was undertaken to determine how the Trust might use it to inform a dynamic response.

Grunig and Hunt set out four models of communication within their Excellence Theory as a way of categorising the type of communications that organisations may practise.

During normal times, the Trust would focus on communicating using the methods in Model 4 – Two-Way Symmetrical communications and by engaging in a dialogue with stakeholders for example, by holding consultations and offering feedback routes on hospital services.

Sometimes the Trust may move to Model 3 – Two-Way Asymmetrical Model if forced, for example, to communicate a decision that did not include any public discussion on the subject such as an increase to car parking charges at hospital sites.

During the cyber-attack, the Trust was forced out of necessity to move to a different model of communication, Model 2 – Public Information Model. The decision to do this was based on a number of factors:

- The majority of the population in the area the Trust serves were elderly.

- Patients needed to have clear information that could not be ambiguous.

- Each update provided from the Trust gave information for a number of departments – it needed to be clear who the message was talking to.

Although this was done out of necessity, it did impact on the ability of the Trust to understand who had, and had not, received the message.

A review of statements released by the Trust during the crisis period demonstrated this shift to the Public Information Model as evidenced by these extracts:

“We continue to experience difficulties with our clinical information systems following the NHS cyber-attack on Friday. Patient safety is being maintained.”

“We are working hard to restore systems and we would like to reassure patients and the public that all patient information is safe, and will be available to our clinicians once the systems are back up and running.”

At this point in the crisis, the Trust’s Communications team could still update the front page of the Trust’s website as required. However, it was also important to consider sharing statements with local media due to the high percentage of the local population that listened to local radio and read the local newspaper.

Marra, cited in Fearn-Banks, builds on the excellence theory model and suggests that an organisation which practises two-way symmetrical communication before a crisis, fares better during a crisis response.

Analysis of media coverage during the crisis

During a crisis, communications practitioners are well versed in the requirement to contact various stakeholders and media. Fearn-Banks goes further to explain that the communication must begin within the first hour following notification that the crisis has occurred, the Golden Hour.

The Trust did not release a statement directly during this time but did direct media queries to NHS Digital which released the following example statements:

“A number of NHS organisations have reported to NHS Digital that they have been affected by a ransomware attack.”

“NHS Digital is working closely with the National Cyber Security Centre, the Department of Health and NHS England to support affected organisations and ensure patient safety is protected.”

Fearn-Banks classifies the four stages of a crisis in the media. This categorisation was used to analyse examples of news commentary with a relationship to the crisis caused by the cyber-attack, the NHS and the Trust.

Stage 1 – Breaking news, the immediate shock – ends when causes and explanations are presented.

During stage one, the majority of news reports focussed on the scale of the attack and speculated on the cause, as shown by this example from The Guardian published during this stage:

“A ransomware cyber-attack that may have originated from the theft of “cyber weapons” linked to the US government has hobbled hospitals in England and spread to countries across the world.”

Stage 2 – Begins when concrete details are becoming available, an example of the media coverage during this stage from the BBC was:

“A massive cyber-attack using tools believed to have been stolen from the US National Security Agency (NSA) has struck organisations around the world.”

“Among the worst hit was the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Scotland.”

Stage 3 – Often involves analysis of the crisis and its aftermath and an example from the BBC was representative of this stage:

“Experts are warning that there could be further ransomware cases this week after the global cyber-attack. So, what has happened and how can organisations and individuals protect themselves from such attacks?”

Stage 4 – Evaluation and critique – were warnings heeded and organisations prepared? An example from the BBC was representative of this stage, showing the increase in focus on the organisations affected.

“The board of one of the worst hit trusts in the NHS cyber-attacks had discussed its lack of plans to tackle a cyber security breach just days before last Friday’s attacks.”

Ethical considerations

The four dimensions of the Potter Box model were used in the research to reflect on the ethical implications of the crisis communications approach adopted by the Trust during the cyber-attack.

Empirical definition – Should the Trust have moved from its instructional messaging for patients, to focus more on what was being done to resolve the situation?

Identifying values – Introducing more information into already lengthy statements could have diluted the message and confused patients.

Appeal to ethical principles – The communication approach could also be considered in the context of the four ethical pillars of the healthcare system. A consideration of these made it clear that the only option that fell under these principles was the communications approach adopted by the Trust to continue with a focus on the instructional messaging for the benefit of the patients.

Choosing loyalties – Two options were apparent in this case, loyalty to patients or to that of the Trust and its employees. Although the Trust was a victim of the attack in this case, arguably the real victims of the attack were the patients who could not access the care they needed. Therefore, it could be concluded that the Trust’s loyalty should have been to the patients.

By reviewing the decision process methodically using this model, it was clear to see that the communications action taken by the Trust was the most ethical option. If the situation were to happen again, the Trust should follow this approach again to ensure that patients were at the heart of any external communications activity.

Delving into the crisis using Fink’s Crisis Lifecycle

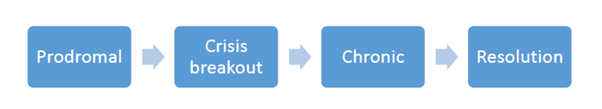

The research for this case study used a number of academic models combined with secondary research to analyse the Trust’s communications response. Fink’s Crisis Lifecycle, was used to organise some of the research findings and other evidence to map the Trust’s approach to crisis communications and review this against each stage of the lifecycle.

Prodromal stage

Summary:

What was the Trust’s communications response during the prodromal period?

- The cyber-attack threat was not picked up as part of horizon scanning activity.

- The majority of communications crisis plans were held on computers.

- There was a lack of preparation between NHS organisations.

When in the prodromal stage there were a number of factors that could have been considered a trigger and, if addressed in a timely manner, may have helped to mitigate the crisis.

Firstly, in 2014, three years before the attack, the Department of Health and Social Care wrote to all NHS organisations saying it was “essential they had robust plans to migrate away from old software by 2015” but there was no reporting mechanism in place for this and the Trust continued to deploy the out-of-date software past the deadline.

Secondly, a number of hospital trusts had been hit by cyber-attacks in the previous year and although this was known by the Trust’s IT department, emergency planning did not identify it as a cause for consideration in the regular update cycle.

Crisis breakout stage

Summary:

What was the Trust’s communications response during the crisis breakout?

- Media enquiries were deferred to NHS Digital.

- Identified key contacts at other hospital sites to relay messages for sharing on that site.

- Established a pool of runners in the Trust’s hospitals who could disseminate handwritten updates across hospital departments.

- Drafted instructional statements for clinical staff to share with patients already in the hospital.

- Drafted instructional statements for switchboard operators to share with concerned patients and families contacting the Trust.

- Drafted external instructional statements for patients due to attend hospital in the coming days and shared these via social media channels.

- Shared external statements for patients via telephone with local media contacts.

The WannaCry cyber-attack hit the Trust via the internal NHS network used by NHS organisations across the country. All networked IT systems were quickly shutdown across the Trust in response to the attack, the Trust’s Crisis Management Team (CMT) was activated and an internal major incident was declared.

Patients were still arriving at the Trust’s hospitals at this point and there were many in clinics who were witnessing first-hand the shutdown of the systems during their appointments. Consequently, the Trust’s focus was on getting clear messages out to employees and patients as quickly as possible.

During the first hour (the Golden Hour) of the attack, the Trust directed media calls to NHS Digital, who manage the overall NHS IT infrastructure, while establishing the extent of the hack and the implications for patients. The decision to do this was based on a number of factors:

- NHS Digital had the national overview and could comment on the attack itself.

- The Trust’s Communications team was short staffed.

- The Trust was still assessing the impact on services, so no clear messaging could be shared.

Once agreed, internal messaging focused on what had happened, and what employees were being asked to do to support the recovery.

Externally, as identified by the stakeholder analysis, the key stakeholder for communications were patients and providing clear and concise communication for them was a key feature in this stage.

All messages were instructional (the Public Information Model) to make sure patients could understand what they physically had to do.

Chronic stage

Summary:

What was the Trust’s communications response during the chronic period?

- Directed patients to social media channels and website for updates.

- Focus continued on external instructional information for patients.

- A decrease of information needed for employees, due to weekend working and clinical employees moving to entire paper-based systems.

- One member of Communications Team acted as point of contact for CMT over weekend.

- Declined requests for spokesperson for media interviews due to focus on getting back up and running.

- Declined to comment on reports that the Trust was unprepared for cyber-attack.

Throughout the days following the attack the Trust continued to suffer the impact of the cyber-attack, and there was media interest in how the attack happened and why the Trust continued to be so severely impacted when many other hospitals were coming back online. The reasons for this included UK Government rhetoric that 97% of hospitals were now “working normally” and only six were still experiencing issues.

In response, the Trust’s CMT agreed to continue with only providing instructional information (the Public Information Model) while services were still impacted to ensure patients remained informed of when they should and shouldn’t attend hospital, due to the confusion created by the Government’s messaging.

Resolution stage

Summary:

What was the Trust’s communications response during the resolution phase?

- A review, with other NHS organisations, of a future co-ordinated communications response.

- Trust communications review with updated plans developed.

- Offline resource box created.

- Regular scenario planning activity in place with emergency planning team.

The Trust declared itself as running normally five days after the cyber-attack hit. It took longer to recover than other hospitals and this singled it out for more media scrutiny than it perhaps would have received if it had been part of a larger group.

Fearn-Banks states that hospitals usually stay in business no matter what misdeeds they do and this was true in this crisis response, but the reputational impact of the crisis on the Trust still needed to be considered

Recommendations

A number of recommendations for action to prepare for future crisis communication scenarios were identified from the research findings:

- Take ownership of the messaging, particularly during the Golden Hour, rather than deferring this responsibility to NHS Digital.

- Establish a single point of contact for reporting to other NHS organisations.

- Bring in additional communications support and resources to increase the capability to deal with communication priorities, including dealing with media enquiries and social media monitoring.

- Establish quarterly horizon scanning sessions, led by the Communications Team, with other departments (such as IT) to identify potential risks.

What I learnt from completing my crisis communication diploma assignment

Completing my crisis communication diploma and the assignment really helped me to understand the importance of horizon scanning to identify emerging threats and to properly prepare for them.

At the Trust, we had anticipated the threats of terrorist attacks, major road traffic accidents and natural disasters, but a cyber-attack threat had not really been considered within our regular crisis planning.

This also exposed the importance of the Communications Team being really included and embedded in business continuity and crisis planning, and not being brought in as an afterthought or just when a crisis had occurred. Communicators often bring a broader perspective to the planning table, which extends beyond the obvious impacts of IT failures, to help organisations consider the reputational aspects of issues and events. Things that might not be obvious to others in the organisation, but which also need to be considered.

For example, the WannaCry crisis happened less than four weeks before a snap general election and campaigning was in full swing. This meant that all government related organisations, including the NHS, were in purdah and we hadn’t thought through what we would be able to say, and not say, in a crisis in those circumstances. That’s probably an issue that only a communications person would be able to identify and resolve during business continuity planning.

As a small communications team in the Trust, it was tough to manage and deliver all the activity we needed to when the crisis hit us. Looking back, we didn’t have enough people we could bring in quickly from elsewhere in the Trust and NHS to help us, and we hadn’t planned for that as an option.

In my current role, I lead on a lot of the crisis communications preparedness activity and have brought that learning into my planning. Being able to bring in extra communications help in a crisis, is something that I’m really conscious of when putting together my current crisis communication plans.

So, thinking about how we could identify and mobilise the right people if we needed extra help in a certain place in the organisation? And also, what we could do digitally, so that people don’t have to be physically present in a certain place? That sort of thinking is really changing how we would approach communication during a crisis.

On the theoretical side, the Griffin’s Bowtie analysis I completed was really helpful in the context of horizon scanning. This really makes you think in a different way about identifying risks and issues and prioritising them for action in crisis planning. So, identifying what is the absolute worst-case scenario as a starting point to work back from, to compartmentalise and prioritise risks and issues.

Completing the course has also increased my confidence as a communicator. I feel that I am now better placed, and able, to push for communications to be involved within a higher level of planning, rather than just accepting that we will be brought in as an afterthought. I’m also now much more able to say that some of the things we are sometimes asked to do as communicators during crisis planning are not our responsibility.

The course has helped me to be really clear about what we can offer before, during, and post-crisis, and given me the confidence to speak up and say what our role should actually be.

References

Bowtie Analysis – In Griffin, A. 2014, Crisis Issues and Reputation Management, Kogan Page. p129.

Grunig, J and Hunt, T. 1984, Managing Public Relations, Harcourt College Publishers.

Fearn-Banks, K. 1995, Crisis Communications: A Casebook Approach, Routledge.

Potter Box – Cited in Carveth, R. Ferraris, C. Backus, N. 2006, Applying the Potter Box to Merck’s Actions regarding the Painkiller Vioxx, Proceedings of the 2006 Association for Business Communication Annual Convention. p6.

Four Pillars of Medical Ethics – Dr Paul Nisselle, 2015, Essential Learning, Law and Ethics https://www.medicalprotection.org/uk/articles/essential-learning-law-and-ethics

Fink, S. 1986, Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable, iUniverse.