Lifting the lid on waste

How the London Borough of Barking & Dagenham could use communications planning to inform recycling participation

About the author

Martin Flegg Chart.PR FCIPR is a PR professional specialising in internal communication. He is also a guest tutor and assessor for PR Academy on CIPR qualification courses.

This case study is based on a CIPR Professional PR Diploma assignment by Jack Shaw, edited by Martin Flegg.

Across the London Borough of Barking & Dagenham the recycling rate in 2019-20 was 25.2%, compared to 44.7% nationally in 2018. Each household generated over 850kg of waste, one of the highest levels of waste per household across London, and at £90 per tonne Landfill Tax costs councils eight times more than it would to recycle waste.

The Greater London Authority’s (GLA) Municipal Waste Strategy (2011) is London’s overarching waste management framework and set London councils a recycling target of 60% of household waste by the end of 2031. As part of its Environment Strategy, the GLA also requires councils to reduce waste per household to 790kg by April 2021 with a view of turning London into a “zero waste city” by 2026, sending no recyclables to landfill.

As part of its ambition to become the “green capital” of London, Barking & Dagenham identified three strategic objectives in its Waste Strategy (2016-20):

- Reduce contamination between household waste and recyclables – which renders recyclables unrecyclable,

- Reduce the volume of waste per household by 6% each year,

- Increase recycling participation so that it is on par with London’s average recycling rate of 31% by 2020.

Doing so would save the council an estimated £2 million over four years.

The council identified three broad PR objectives: inform, educate and change negative recycling behaviours.

To understand the role strategic communications could play in increasing recycling and reducing waste, greater insight into the problem was required.

Research approach, sources and methodologies

A broad range of sources were critically analysed to inform future communications planning.

- Quantitative research into the demographic profile of negative recycling behaviours, including housing type (flats verses houses), tenure (renting versus owning), age distribution and family structure.

- Qualitative research into the barriers preventing people from recycling – the psychographic profile – drawing on the social sciences, the council’s own consultation exercise, and case studies from the Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP), Resource London (RL) and individual local authorities.

- Polling by Ipsos Mori and YouGov of the recycling knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of Britons. The British Social Attitudes (BSA) Survey also enabled a longitudinal analysis of national trends in recycling attitudes.

- PESTLE and SWOT analyses of the external and internal operating environments.

- Consideration of communications planning models such as EAST (Easy, Attractive, Social, Timely) and RADAR (Research, Assess, Decide, Act, Review).

- Stakeholder mapping across demographic and psychographic profiles, drawing on James Grunig’s situational theory.

The four key stakeholder groups

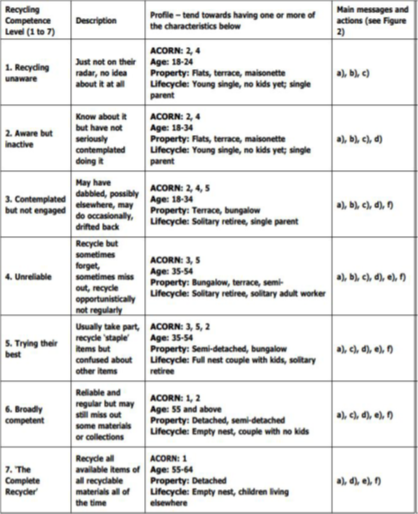

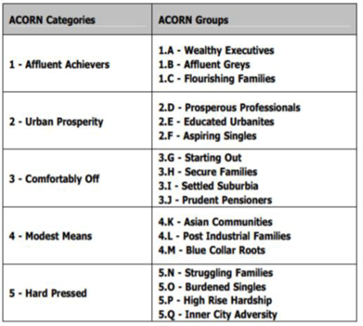

The research revealed that there were four key stakeholder groups which exhibit poor recycling behaviours across London. The stakeholders within these groups fall within ACORN’s socio-economic classifications 2, 4 and 5: comfortable urbanites, households of modest means and the hard-pressed. However, in practice there are likely to be few in Barking & Dagenham that neatly fit within ACORN and the recycling competence levels linked to socio-economic classifications used by WRAP.

- 18-34-year-olds

London’s 18-34-year-olds are the worst performing recyclers. According to RL, 90% contaminated their recycling bins, compared to 74% of the over-55s. This aligns with research by YouGov which revealed that just 24% of 18-24-year-olds know what materials can be recycled, the lowest percentage across all age groups and just half that of the over-55s.

Feedback from the council’s largest ever consultation exercise encouraged the council to work with the youngest in the borough because they are “keen to save the environment”. However, this research and situational analysis found that there was no correlation between views on climate change and levels of recycling.

- Single-parent households

Single-parent households also exhibit negative recycling behaviours, with 32% of households identifying as “not committed” recyclers, higher than any other group with the exception of young people.viii A decline in average household sizes across local authorities is associated with higher levels of waste and Barking & Dagenham has the highest proportion of single-parent households at 14%, double the national average.

- Occupants of purpose-built flats

Compared with households in detached homes, occupants of purpose-built flats are 12 times more likely to avoid recycling. This stakeholder group comprises of a quarter of households in Barking & Dagenham (18,756).

- Tenants in rented accommodation

Across London low levels of home ownership also correspond with low levels of recycling. The research in this area is under-developed, but the rising popularity of Houses of Multiple Occupancy where three or more tenants share communal spaces has been cited as one reason behind poor recycling performance.

Across all these stakeholder groups strategic communications has proven to be an effective tool to tackle negative recycling behaviours, regardless of stakeholder group: the GLA concluded that London authorities with ongoing communication programmes have on average higher levels of recycling.

It should, however, be caveated that driving positive recycling habits also needs to conducted alongside tackling negative ones, such as high levels of waste. Writing in the Harvard Business Review, Remi Trudel identified that recyclers are more likely to give themselves a ‘free pass’ to generate more waste because the “positive emotions associated with recycling overpower the negative emotions, such as guilt” associated with waste generation – what social scientists call moral licensing.

Insights into why these groups don’t recycle

According to WRAP’s Barriers to Recycling report, there are three reasons why people don’t recycle.

- Knowledge

- Attitudes and perceptions

- Behaviour

While these barriers were found to be shared by all of the four stakeholder groups, knowledge gaps, attitudes, perceptions and behaviours vary in degree and in kind within them. Of the most prominent attitudinal barriers – distrust, status quo and identity biases, time, ease and a lack of agency and ownership – 18-34 year olds were associated with most of them bar ownership, while barriers facing tenants, occupants of purpose-built flats and single-parents households centred around ownership, time and ease.

Younger people – 18 to 34 year olds

Alongside a lack of knowledge, negative recycling behaviours amongst young people are the result of distrust in local authorities, a perceived lack of agency, a status quo bias in which doing nothing is easier, or an identity bias in which young people think people ‘like them’ don’t recycle.

The “status quo bias”

Ethnographic research of 18-34-year-old Londoners has highlighted the complexity surrounding their recycling behaviours. Researchers unveiled a “status quo bias” whereby 18-34-year-olds wanted to recycle but that wasn’t enough to jolt them into action.

While the knowledge gap is particularly pronounced in 18-24-year-olds, knowledge is rarely sought by 25-34-year-olds either. Polling by WRAP identified that 48% of recyclers continue to bin recyclates because they aren’t sure what items can be recycled.

Filling in this knowledge gap alone is not enough, according to research by Sol Hart and Erik Nesbit, who found that greater knowledge of climate change did not automatically produce higher levels of support for mitigation policies, such as recycling. In some cases, facts alone even created a “boomerang effect” and increased message resistance.xv Polling by the BSA also established that recycling rates remain consistent regardless of the level of concern about climate change, which might suggest that drawing on value propositions as communications tools – focusing on the virtuous or intrinsic reasons for recycling, such as saving the planet – are unlikely to translate into recycling behaviours.

Though exposure to knowledge can increase the sense of agency amongst 18-34-year-olds, which itself is a motivating factor, it is only one. This lack of motivation to change behaviour is also a common theme amongst 18-34-year-olds. Both motivational levers and knowledge are necessary to change attitudes and drive better recycling behaviours, but they must also be ingrained to such a degree that recycling participation becomes habitual.

While a strong emphasis must be placed on motivation, motivation minus knowledge leads to misconceptions, uncertainty and confusion, which ultimately demotivates 18-34-year-olds.

Anecdotal evidence suggests 18-34-year-olds are immune to the power of interpersonal levers because they rarely speak with parents, friends or housemates about recycling, according to RL.

Where interpersonal levers are thought to be most effective is through the “pester power” of school aged children who encourage their parents to recycle more.

The trust gap

Distrust is a recurring theme amongst 18-34-year-olds too. While only one in twenty Brits polled by YouGov said they refuse to recycle until they’re confident their recycling isn’t going to landfill, RL identified a dichotomy amongst 18-34-year-old Londoners who felt that it was their local authorities’ responsibility to support them to recycle yet at the same time were deeply distrustful of them.

Though the level of distrust may make targeted communications activity aimed at this stakeholder group more difficult, international research by Ipsos Mori suggests it is not linked to the performance of recycling services but to the perception of councils. It is a PR issue rather than a service delivery one. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Brits rated recycling services as good while 60% said local rules were clear, both well above the global average.

The “identity bias”

Ethnographic research has also revealed an “identity bias” amongst 18-34-year-olds, tenants and occupants of purpose-built flats with low levels of recycling participation.

According to research by RL, participants said recyclers were not like them: they’re homeowners, in higher socio-economic classifications or have free time. The concept of time is relevant because higher levels of recycling participation was contingent on ease and immediacy, which these stakeholders internalised as part of their identity. Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine, Brian Iacoviello, calls this the “crude cost-benefit analysis” stakeholders make when deciding what matters to them, “which emphasises the immediate (saving time) over the long-term (saving the planet).”

Social scientists have drawn similar conclusions. Trudel identified that recycling participation increases when identity is attached to an item – in this case, participants’ name on a Starbucks cup – which suggests that one way of bridging the “identity bias” is by introducing an element of personalisation into communications.

18-34-year-olds – Stakeholder group summary

Though recycling isn’t on the radar of the youngest (namely 18-24-year-olds), the majority are aware insofar as they recognise that a problem exists – the climate emergency. Grunig calls this problem recognition. Yet 18-34-year-olds have the lowest levels of recycling participation because they are unlikely to make the connection between the problem and their action. They don’t seriously contemplate recycling and when they do recycle, they are likely to do so for a short period of time before returning to habitual non-recycling behaviours. In this respect 18-34-year-olds are also passive stakeholders insofar as they are unlikely to become active until persuaded to do so, what Grunig says requires “attention-grabbing communications”.

Tenants and occupants of purpose-built flats

The barriers to recycling amongst tenants and occupants of purpose-built flats centres around the perception of ownership over recycling, as well as access and time. More transient tenants bring learned behaviours from different local authorities – which have different rules – with them wherever they move.

A sense of ownership?

While there is a good degree of crossover between the psychographic profiles of the four stakeholder groups, a lack of ownership was most prominent in tenants (housing tenure) and occupants of purpose-built flats (housing type).

The high turnover of tenants, multiple-tenant households, short-term lettings and the feeling that a property ‘isn’t their own’ has given rise to negative recycling behaviours. On a practical level transience presents a challenge for communication practitioners, as does limited access to individual households in purpose-built flats.

The lack of ownership in particular has played out in multiple ways. As just one of dozens of users of communal binstores, individual households in purpose-built flats can avoid recycling unnoticed. They are emboldened by anonymity. RL found evidence that the reverse is also true, with an element of ‘green shaming’ in close knit estates which acted as an impetus to improve recycling behaviour, but in general an absence of ownership enables tenants and occupants of purpose-built flats to rationalise away any guilt associated with their negative recycling behaviours. As a result, the volume of contamination is often high amongst this stakeholder group since it only takes one tenant or one household to recycle incorrectly.

Despite these challenges, a joint communications programme delivered by housing association Peabody and six inner-London boroughs with a strong focus on making recycling more convenient saw recycling participation rise by 26% and contamination fall by 24%.

Tenants and Occupants of purpose-built flats – Stakeholder group summary

Though tenants share a similar level of problem recognition as 18-34-year-olds, their knowledge gap is smaller. Higher recycling participation suggest tenants are aware and more likely to process information, but in doing so recognise constraints on their ability to recycle. Tenants’ connectedness to recycling – Grunig’s ‘level of involvement’ – is also contingent on their sense of ownership. Like tenants, occupants of purpose-built flats are aware but recognise the constraints on their behaviour. Their behaviour (access, communal bin, recycling is more laborious) rather than their attitudes (lack of ownership) are the biggest constraints.

Single-parent households

For single-parent households the barriers were found to centre on behavioural factors: time, lack of established routine, and recycling not being a priority.

Single-parent households – Stakeholder group summary

The recycling behaviours exhibited by single-parent households are more diffuse. They include committed recyclers and non-recyclers alike but are predominantly composed of latent and aware single-parent households. Latent single-parent households have comparatively low levels of involvement and problem recognition, the evidence being that behind young people single-parent households are the most likely to avoid recycling. Further research is needed to assess whether single-parent households are more prone to apathy on all issues as a result of the physical and cognitive demands of parenthood.

Recommendations

The analysis of the state of recycling participation across Barking & Dagenham ensures that future strategic communication activity is rooted in evidence, and a number of PR objectives were identified from the situational analysis and research. These focused on process, awareness and action.

Process objective: conduct a borough-wide waste composition analysis over 12 months to understand the composition of waste and what materials are contaminating recycling bins. (An analysis of waste by Norfolk Waste Partnership found that significant amounts of plastic recyclables were being binned, which informed their PR campaign on how to prepare recyclates for recycling.)

Process objective: consult with a representative cross-section of single-parent households, tenants, 18-34-year-olds and occupants of purpose-built flats across the borough over 12 months to understand the drivers behind their recycling behaviour.xxv (As the third most deprived borough in London, Barking & Dagenham’s socio-economic classification is more congregated toward the bottom of the ACORN scale, 4 and 5. In-borough research is required to be to identify to what degree barriers in London vary across socio-economic classifications)

Awareness objective: decrease the recycling knowledge gap by 10% amongst 18-24-year olds over a 12-month period.

Action objective: increase levels of recycling amongst 18-34-year-olds by 10% over a 12-month period.

Action objective: increase levels of recycling amongst occupants of purpose-built flats by 20% over a 12-month period.

Action objective: reduce the percentage of single-parent households that identify as ‘non-recyclers’ from 9% to 6% over a 12-month period.

Jack Shaw – What I learnt from completing my assignment

“Many local authorities run PR and communication campaigns about waste recycling which often result in short-term increases in recycling rates. However, they usually aren’t sustained enough, or grounded in the level of research and evidence required, to create and embed the necessary habitual behaviours and attitudinal change over the longer-term. Stickers with messages on bins eventually lose their meaning or are damaged and washed away, for example, so campaigns need to be multi-pronged and sustained for longer to create lasting behaviour change.

My assignment research demonstrated that common assumptions made by councils are not always supported by the evidence. There is no evidence that mosque visits, which formed part of the campaign activity in Barking & Dagenham, positively impacted recycling performance. Likewise, the evidence for ‘pester power’ is under-developed.

For younger adults, I found that talking about recycling is not part of their lexicon and assumptions that they support climate change activism, and are therefore more likely to recycle, was seemingly not the case.

With this in mind, my biggest takeaway from completing my diploma assignment was that impactful PR and communications activity needs to be grounded in research and evidence and not in assumptions. That research doesn’t necessarily have to be in depth or take too much time, but it should be an iterative process as part of communications planning.

Though I left Barking & Dagenham Council a few years ago, communication is an important part of the work I now do in another London council. In that capacity, my personal priority is to see a more rigorous focus on evidence-based communications. Too much emphasis is placed on output – the amount of work communications teams produce, rather than what it achieves in terms of impact and influencing attitudes and behaviours. That’s something I’m really keen to turn on its head.

As I continue with my studies, I now have a better appreciation of communication plans and communication strategies. In my new role another personal mission of mine is for communications to be seen as a more strategic function. That means empowering communications experts and tackling the idea that everyone knows how to ‘do comms’. Completing the course has given me the knowledge and confidence to be able to say to colleagues that I know what I’m doing.

I’m now also much more aware of the influence the built environment has on communication. When I walk down the street and see signage, I’m looking beyond the content and thinking about how the decision was made for it to be placed in that specific location, and why that location is more impactful than elsewhere. I feel like an anthropologist, deconstructing what I see and trying to work out what the wider meaning of it is!

When I started my diploma course, I had never heard of any communication theory whatsoever. Understanding theory has enabled me to build a framework of wider understanding that has been transformative in the work I now do. The course has demonstrated the practical application of theory, which has been really helpful. It’s given me the ability to constructively critique proposed communication plans and evaluate communications activity and left me with two abiding questions: how do you know, and where is the evidence?

It’s been a real challenge for me studying during a pandemic. I’m looking forward to completing the course in person, because I prefer that way of learning, and blending online study and a full-time job has been tough. At the same time, it’s been fun learning new things and being able to immediately put them into practice in my day job.”

Appendix 1 – ACORN classifications

Appendix 2 – Recycling competence levels used by WRAP